*

There are cockroaches in the kitchen. I don’t know what’s happened, but they’re everywhere. Maybe our neighbor’s frogs died in the earthquake and the cockroaches have multiplied. Maybe they’ve always been there, under the house, and have now come up through the rubble. The boy and I squash them under the soles of our shoes.

*

If I could talk to Homer once more, I’d start:

Can I ask you a question, Homer?

Fire away, Owen.

What’s the last thing to disappear?

I’m not sure what you’re referring to, Owen.

To death, of course.

Did you know that certain animals can exist without their heads?

*

While we’re treading on insects in the kitchen, the boy tells me that if you cut a cockroach’s head off, it goes on living for two weeks. He says he learned that at school. I get a fit of giggles. So does he. The baby doesn’t laugh: she gazes at us in serene silence.

*

I believe I would have preferred just to go blind. Unblindness and disappearing, erasing myself while I begin to see others clearly again, doesn’t seem to be the best way to end my days. I’d already gotten completely used to the idea of not seeing anything or anyone. And now what happens is that Nella appears to me in the bathroom. Pound in the Reposet. A while ago, I thought I heard, very clearly, the slightly nasal voice of Guty Cárdenas singing “Un rayito de sol.”

From my briefcase, I take out the picture of the evening of the Moor . I’m sure I was there, I remember it. In any case, I don’t think I’ll go back to the photography studio. I don’t want to leave the house. In fact, I think I’ll call in sick tomorrow.

*

We’ve finally finished killing all the cockroaches. I tell the boy to get under the table. We’re going to make a bed and sleep here, I say.

*

Someone knocks. I get up from my chair and head to the door of the apartment. As I begin to open it, I hear a din like thousands of cockroaches’ tiny feet going up and down the stairs of the building. A slow, paralyzing fear settles in my stomach and seeps down into my limbs. My legs become rigid and a tremor shakes my hands. I double-lock the door and head to the bedroom, sliding one hand along the wall of newspaper that now almost completely covers the left side of the passage.

*

Why do we have to sleep under the table, Mama? Can’t we sleep on top?

No, it’s dangerous. We’re going to sleep under it.

Like cats?

Yes, like three little cats.

*

I go into the bedroom and Federico is shaving his legs by the lamp next to my bed. Beside him, sitting at my dressing table, Z is cleaning his spectacles. I don’t say anything — I was brought up to believe it’s always better not to make waves, although my first instinct is to tell Federico it was about time he got rid of all that leg hair. They’re taking up all my space. I hurry back to the kitchen, pour myself a glass of water with an inch of whisky, and gulp it down. The cats are under the table. Maybe I can lie down on top of the table, next to the orange tree. That way I can think about the novel a little longer. Maybe I can try to get some sleep.

*

I try to get some sleep under the kitchen table with the two children huddled against my body, covering each of them with an arm. I’m afraid of the darkness because the cockroaches might come out for a walk and we won’t see them. I’m woken by the sound of their little feet, scratching on the cement or the metal of the fridge. I cover the children’s ears so the cockroaches can’t get in, so they can’t get into their dreams.

What’s that noise, Mama?

Nothing.

*

I take off my blazer, fold it to make a pillow, and get onto the table.

*

I think it’s the cockroaches, Mama.

Or maybe it’s your papa.

*

As I lie in the darkness of the kitchen, eyes wide open, I hear the buzzing of a fly. Or maybe a mosquito. The sound turns into the distant siren of an ambulance that never quite arrives, returns to being a fly, and goes back to being a siren. I can’t see the mosquito or fly, of course. But when it comes close I swat it. I wonder if this is going to be my last handle on the world: a Doppler effect that comes to nothing, that never finishes. I sweat, tremble, turn over on one side on the hard wooden surface. William Carlos Williams comes in through the door and says:

I’ve spent the whole day delivering children in ambulances. Why don’t women give birth in hospitals anymore?

I don’t know.

If you don’t mind, Gilberto, I’ll just use your sink to wash my hands.

Go ahead, William. Or is it Carlos?

I take my blazer from under my head, cover my face with it, and try to sleep.

*

No, Mama, it’s flies. And mosquitos. During the day, they hide inside the shower and at night they bite us.

*

It’s terribly hot in the kitchen. I uncover my face. William Carlos has finished washing his obstetrician’s hands and is watching me, standing at the foot of the table, like a surgeon about to begin his rounds. I say:

What do you think of this couplet I just wrote? Dead fly song of not seeing anything, not hearing anything, that nothing is.

Not bad. A bit like Emily Dickinson, but not bad.

He checks my pulse and tells me I’ll be O.K. Then he leaves the kitchen. I cover my face again. The flies or mosquitos are still buzzing nearby.

*

The baby has woken up and is crying. The boy and I try to calm her.

Cradle her, suggests the boy.

Cradle her?

Yes, to see if it calms her down.

I rock her in my arms. Nothing. She keeps on crying. Her sobs fill the room. We get out from under the table and walk around the kitchen.

Why don’t we sing to her, Mama?

*

I think the mosquitos are voices. I can distinguish two: one belonging to a little boy, and the other to a baby. The baby cries a lot and the child sings a disturbing nursery rhyme.

*

The boy sings. He has a beautiful, tuneful voice: Autumn leaves are falling down, falling down, falling down. Autumn leaves are falling down and Papa’s missing.

*

I don’t want to hear anything, song of not seeing anything. Beside me, in the white darkness, I hear a soft laugh, the merry chortle of a baby. I feel the blazer that covers my eyes rising, the heat of the room entering and shaking my body, the excited voice of a little boy beating my face:

Found!

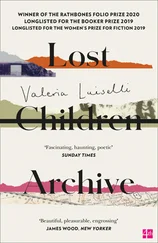

CHRISTINA MACSWEENEY has an MA in literary translation from the University of East Anglia and specializes in Latin American fiction. Her translations have previously appeared in a variety of online sites and literary magazines. She has also translated Valeria Luiselli’s volume of essays, Sidewalks.