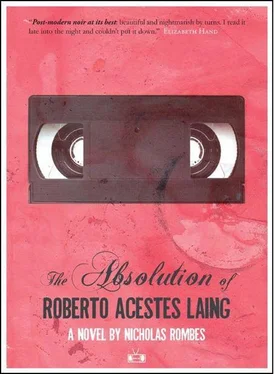

Nicholas Rombes

The Absolution of Roberto Acestes Laing

“So, montage is conflict.”

— Sergei Eisenstein

“On the edge of non-existence and hallucination, of a reality that, if I acknowledge it, annihilates me. There, abject and abjection are my safeguards. The primers of my culture.”

— Julia Kristeva, from Powers of Horror

“Thou hast removed my soul far off from peace.”

— Lamentations 3:17

“Excuse Emily and her atoms.”

— fragment from an Emily Dickinson “envelope” poem, circa October 1882

Destroyer (1969)

Black Star (mid-1980s)

The Blood Order (1948)

Hutton (1951)

AS FOR R. LAING, WHO CAN BLAME HIM?

There’s going to be a person named Katy, you understand . These were the first words he spoke to me. I kept waiting for Katy. Once, during our conversations, he told me he’d “had people hurt in absentia.” I pondered this, the semantics of this.

I interviewed him over a three-day period during a locust-infested summer in a cramped, hot motel room where, to judge from the morbid condition of things — the rotting brown carpeting, the dresser warped and distended as if it had been waterlogged and then dried out, the heaving, peeling sky-blue wallpaper that suggested infestation — he had paid someone in dubious currency to be left alone. He was wearing something like a scarf. Bright red, I remember that, a scarf that brought to mind the sort of clarity that only happens through the iron-willed exertion of power. Did I see a photograph once of Augusto Pinochet wearing a scarf, as well, and a cracked smile that suggested the terror of pure reason? Laing’s dark skin, reddish hair, large hands, and a pale or cream-colored blazer reminded me of the tropics somehow, and in the weary way that he greeted me it seemed as if he had dragged along with him all the time zones he had passed through to get here, and was existing — at this very moment — in each of them simultaneously. A man in his mid-60s but who looks much younger, as if his exterior aging has stalled while his interior aging continued. He has a shock of white hair and an open face. But, for some reason, when he opened that motel room door the first thing I noticed wasn’t Laing at all but a chair in the corner of the room, a chair that couldn’t possibly have been from the motel . It was situated not on the floor itself, but on an unstable foundation of old books (phonebooks, or so I thought) and newspapers. It looked as if it had been reupholstered recently in blue velvet, but done in such a poor way that the fabric was stretched too tightly in some spots and was bunched up or loose in others. And on the chair — which struck me more as a throne or a throne disguised as a chair — there were several neat stacks of uncased VHS tapes, tapes which I assumed were dubs of the films that I’d been sent here to interview Laing about.

Not that he acted courtly. He welcomed me man to man. He called me by a name that only my grandmother used, as if we had shared some secret history that I had forgotten, and at other times called me “A.” which turned out to be the name (or the initial of the name) of a very dangerous person he fell in with during his librarian/graduate school days. He showed me around the place, as it were. A small room, #228, that smelled of scalded milk and had the feeling of a dungeon to it, not that I’ve ever been in one. A door that opened out onto a narrow cement landing looked down across a vast, gullied parking lot, as if built for a motel ten times larger than this one. A bed stripped of its sheets and covers. The throne-chair in one corner. The motel room TV set, its flat screen spray-painted red, in another corner. A small round table where the interviews took place.

Who among us has the authority, the power, to bind and loose?

I had been sent there on assignment , as they say, but also out of curiosity, my own, as it were, eagerness to come close to the source of a myth. On the surface I was simply here to interview Laing for a short-lived cinema journal dedicated to the preservation of lost films that had been awarded a grant to investigate and report on neglected films. And whose chief editor Edison (that’s what we called him, after Herman Casler, an early film pioneer whose ideas Edison stole, and we called him that because he was a thief himself, but a generous one) I had persuaded, in a rare, belligerent show of confidence, to sign over a large chunk of to fund my excursion by borrowed van from central Pennsylvania into Wisconsin (near the western edge of the Chequamegaon-Nicolet National Forest) to interview Laing, whose obscurity had made him fashionable of late, as if nostalgia for the analog had somehow become nostalgia for Laing and his dirty, mistakist, unrepentant ways. I’m certain others had tracked him down but came to believe that what he told them about the films was unreliable. And yet isn’t unreliability its own form of certainty?

Who was Laing, really? (I can say that the disorienting feeling of depth around him had nothing to do with deep thought, but rather was more akin to the extreme depth-of-field in films like Citizen Kane , that make you feel you might fall into the deep background of the film itself, the background that exists in the space behind the characters.) A librarian specializing not in that category of films we call experimental or avant garde, but rather in films that smuggle these strategies and techniques into films that appear, on their surface, to be more conventional. During one of our conversations he said something to the effect that it was more difficult to make a movie with an experimental and bold vision that many might see rather than a self-proclaimed, willfully obscure avant-garde film. He was rumored to have come from a family whose immense wealth was exceeded only by its internal hatreds, and that he had insinuated himself in the margins of academia so as to have access to a campus office and, more importantly, the institutional letterhead that would allow him to correspond with a false authority to the cinephiles who operated the black markets of film ephemera. Others said he’d had a hand in writing the infamous “KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation” CIA manual which had been distributed to South Vietnamese military officers in the 1960s and which contains references to a “weaponized cinema.” I, however, understood him to be a man who staved off disorder and chaos by sorting, by documenting, by naming. First at a small college in the rolling hills of southern Ohio (an area that’s really a secret part of the Deep South) from around 1965 to 1980, and then, until 2003, at a much larger one in Pennsylvania, where, despite its size, you could hear the lowing of the cows in the summer coming through the open dorm room windows on the breeze, and where he earned a reputation as carefully unbalanced by recommending — against the most conservative impulses of the times — films of the most startling, transgressive, truthful sort, salvaged from auctions and purchased with dubious currency from collectors for whom the shock of the new meant unloading the old. But more than that. Laing received, in his library office, canisters of film from the likes of David Lynch, Michelangelo Antonioni, Aimee Deren (granddaughter of avant-garde film-maker Maya Deren), Agnès Varda, Andrzej Żuławski, Alejandro Jodorowsky, and anonymous others through connections that seemed to involve, I could swear, some dark pact he had made in his youth. Laing had watched, in the privacy of his office — so it was rumored — dozens of short films by these directors and others, films of such simple beauty and implied violence. The sort of films that poisoned you if you saw them at the wrong (or right) age.

Читать дальше

![Nicholas Timmins - The Five Giants [New Edition] - A Biography of the Welfare State](/books/701739/nicholas-timmins-the-five-giants-new-edition-a-thumb.webp)