I jumped to the ground and went out to the hallway. The wind howled and pushed against the glass of the windows. The world outside was pitch-black with faint starlight. I lit a cigarette and asked myself how I could change to keep loving her.

Zoë, when we get home, will Bunny greet us at the door wearing a suit and tie?

Zoë—

Of all the scenes in Angelopoulos’s films, the one that moves me the most is in Alexander the Great . Alexander, “a child of fortune,” adopts a woman in town as his mother, whom he loves. He eventually marries her, and while wearing her white wedding gown, she is shot for resisting the totalitarian regime. For the rest of his life, he loves only her. Alexander returns from the battlefield and enters his room. There is only a bed and, hanging on the wall, his mother’s bloodstained wedding gown. He says to the gown on the wall: Femme, je suis retourné. Then he lies down quietly and sleeps.

And on it flows. I long to lie down quietly by the banks of a blue lake and die… and when I’m dead for my body to be consumed by birds and beasts, leaving only the bone of my brow for Xu… like Alexander, loyal to an everlasting love.

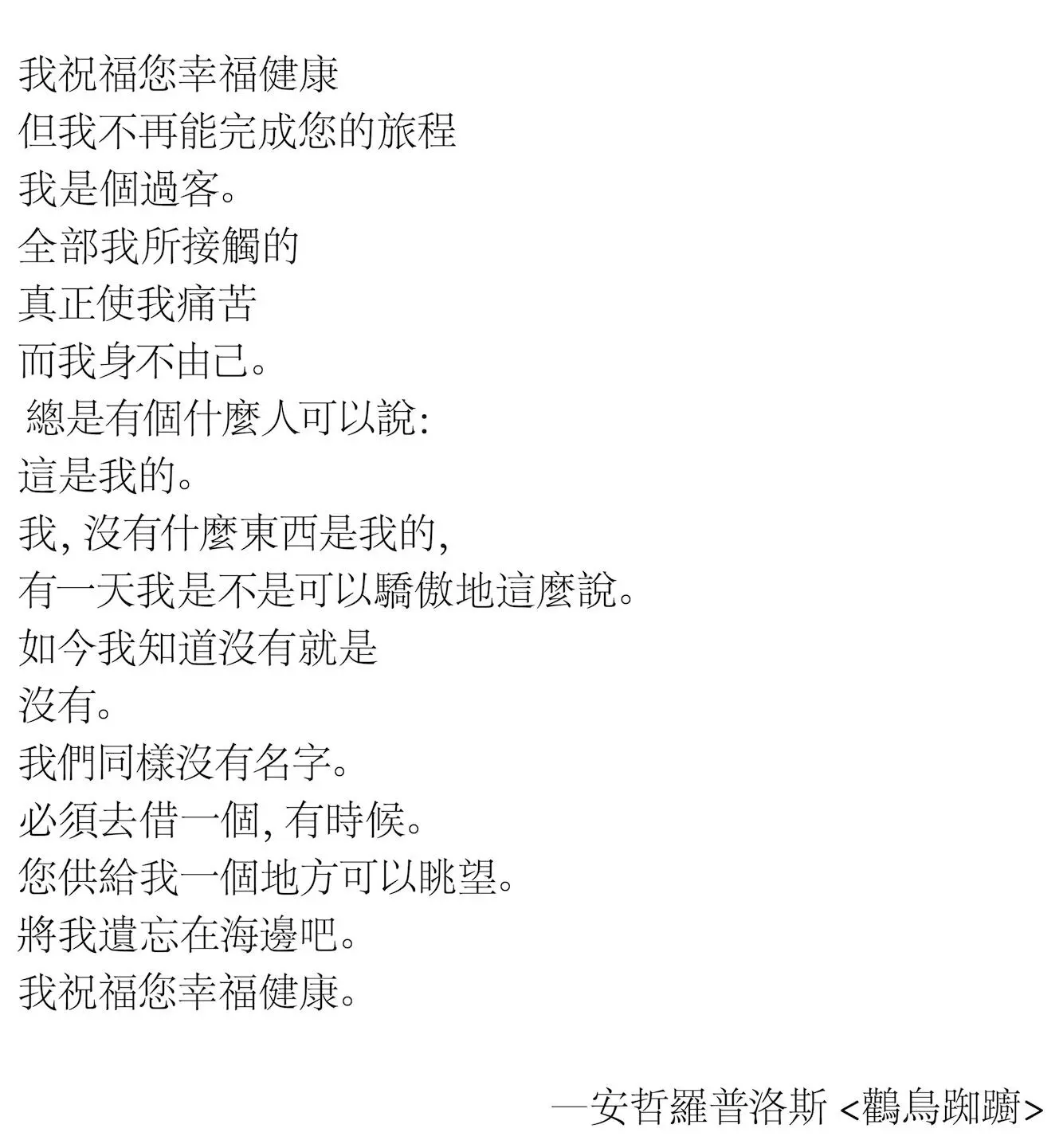

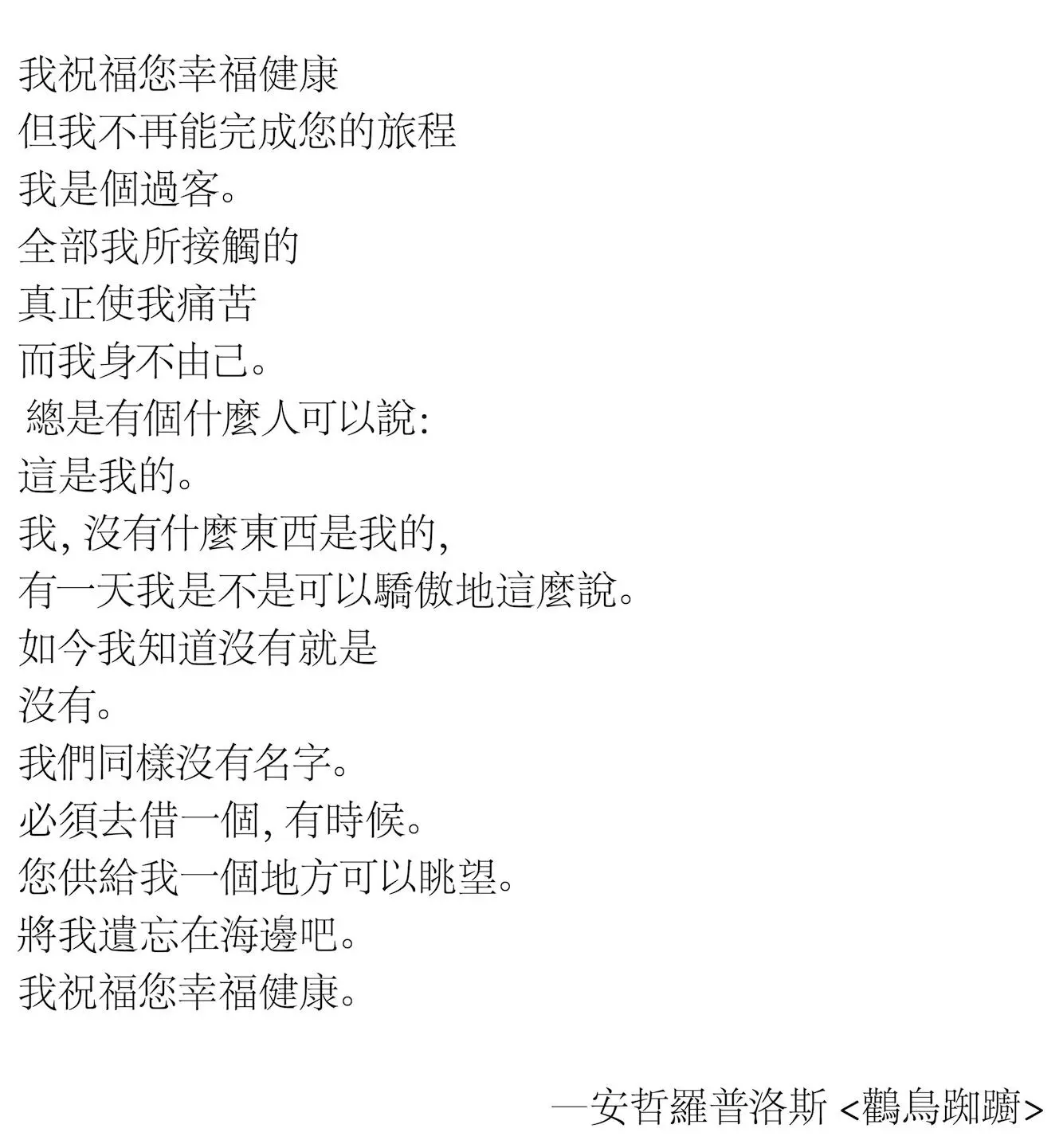

Je vous souhaite bonheur et santé

mais je ne puis accomplir votre voyage

je suis un visiteur.

Tout ce que je touche

me fait réellement souffrir

et puis ne m’appartient pas.

Toujours il se trouve quelqu’un pour dire:

C’est à moi.

Moi j’en ai rien à moi,

avais-je dit un jour avec orgueil

à présent je sais que rien signifie

rien.

Que l’on n’a même pas un nom.

Et qu’il faut en emprunter un, parfois.

Vous pouvez me donner un lieu à regarder.

Oubliez-moi du côté de la mer.

Je vous souhaite bonheur et santé.

— THEO ANGELOPOULOS, Le pas suspendu de la cignogne

I wish you happiness and health

but I cannot complete your journey

I am a visitor.

Everything I touch

causes me real suffering

and does not belong to me.

There is always someone who says:

This is mine.

But I did once say proudly,

I have nothing of my own

for now I know that nothing means

nothing.

That one does not even have a name.

And that sometimes one must borrow one.

You can give me a place to look at.

Forget me by the seaside.

I wish you happiness and health.

— THEO ANGELOPOULOS, The Suspended Step of the Stork

Artifacts of Love: Qiu Miaojin’s Life and Letters

TAIPEI TO PARIS

THOUGH nearly twenty years have passed, the circumstances of Qiu Miaojin’s suicide in Paris at the age of twenty-six still inspire speculation in newspapers, scholarly journals, and across the gamut of social media in Taiwan. How did she die? Who were her lovers? Did she die of a broken heart? Qiu’s breakout novel, an accessible yet mordant work called Notes of a Crocodile (1994), gave voice to a generation of Taiwanese lesbians and earned Qiu a kind of cult status in queer circles. Soon after her death, Notes of a Crocodile won the China Times Honorary Prize for Literature in 1995 and her work catapulted from the margins into the mainstream. Her novels are taught in high schools and universities across the island, and several doctoral dissertations have tried to untangle her complex emotional grammar. At least one tribute memoir has been written (Luo Yijun’s Forgetting Sorrow , 2001), as well as a novelistic reflection by her friend Lai Hsiang-yin ( Thereafter , 2012). Besides reaching a popular audience in Taiwan, Qiu’s books were recently published on the Chinese mainland — an astonishing turn, really, for not even a decade ago the only editions available there were bootleg copies circulating hand to hand in lesbian communities.

How did the dark, experimental meditations of a young Taiwanese lesbian come to attract such a devoted and diverse following? Perhaps Qiu’s success relates to the general cultural receptivity of Taiwan’s capital, Taipei, a city whose flourishing public life and dynamic cultural scene invited a coy comparison in a recent Wall Street Journal profile to Portland, Oregon, as a place where “nature, a decent croissant and rare vinyl increasingly trumps having the latest Rolex.” The city is also widely known as one of the most “gay friendly” in Asia. Yet this kind of snapshot tends to mask not only the boiling tensions underpinning the present “liberalism” in Taipei but also the city’s complex past. Only a decade before Qiu wrote Last Words from Montmartre in Paris, the Taiwanese government had finally lifted nearly forty years of martial law, and it had been little more than a generation since the great split leading to the present deadlock between Taiwan and mainland China. “Gay rights” was a newly coined term in Chinese in the 1990s, and the memory of police raids and harassment in Taipei’s New Park, a notorious and much-loved cruising site under martial law, was still fresh — even as a more liberal regime now tried to “clean up” the park in the name of “democratic and progressive” nationalist policies. It was also during this time that Taiwan began to lobby officially for readmission into the United Nations, having been formally expelled in 1971. As Qiu was completing Last Words from Montmartre , questions of national sovereignty and Taiwanese identity dominated public discourse, and tensions with the mainland escalated until China eventually launched “test” missiles into the Formosa Strait in an effort to influence Taiwan’s first-ever democratic presidential election. And yet if Taipei in the mid-1990s was no Portland, how do we explain Qiu’s warm reception by readers across all walks of life, beyond identity politics, nation, and even language (her books also have been translated into Japanese)? Is it the literary value of her work, or the mysterious, tragic circumstances of her death? Or was she simply in the right place at the right time?

The answer is most likely a mix of the above. The richness of Taiwan’s history is sometimes obscured in the West by a tendency to reduce the country’s cultural identity either to the political tensions that confound cross-strait relations or to its “economic miracle” over the last thirty years. But vertiginous shifts in Taiwan’s political and cultural life over the course of the twentieth century made the island a home to many languages and cultures, and yielded a spectacular literary pluralism. Although the island was a protectorate of the Qing dynasty until 1895, it was ceded to Japan as part of the settlement from the Sino-Japanese War, and thus became a Japanese colony for fifty years, until 1945. During this half century, Taiwanese were forced to speak Japanese in public, and to learn Japanese literature, history, and culture in school, while at the same time the infrastructures for transportation and social welfare (train lines, public works) were put in place that would become a foundation for Taiwan’s economic miracle in the later part of the twentieth century. With the defeat of Japan in the Second World War, however, Taiwan was remanded in 1945 to the rule of the Nationalist Party in China. This initially seemed like good news to many Taiwanese — after half a century of Japanese rule, people were optimistic that a culturally vested Chinese leadership would better represent their interests (and would be more supportive of local dialects). But the new regime enforced the use of standard Mandarin, imposed crippling taxes, and used ruthless force to suppress local dissent and demands for representation. So brutal was this initial period of Nationalist control — involving strict censorship, curfews, “disappearances,” and, most tragically, a 1947 massacre of thousands of Taiwanese dissenters and civilians — that some citizens became nostalgic for the Japanese regime. Nevertheless, after the Chinese Communist Party took control of Mainland China in 1949, the Nationalist leadership was left to rule Taiwan for another fifty years, until the popularly elected Democratic Progressive Party candidate Chen Shui-bian took office in 2000. Whereas Qiu’s grandparents’ generation lived under Japanese colonialism, it was the harsh rule of Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalists that determined the shape of public life for Qiu’s parents’ generation. By the time Qiu was a teenager in the 1980s, she was heir to a unique mix of living traditions and divergent notions of civic life: Japanese modernist aesthetics versus Chinese “anti-Communist” austerity; the experience of — and imperative to articulate — a sense of divided selves, public and private; and increasing access to a broader global “public” of Western-language literatures and cultures. When Qiu was in high school, it was normal for a young urbanite to speak Hokkien at home with her parents, Japanese with her grandparents, and Mandarin on the streets — all the while taking classes in English, French, Korean, and possibly other languages.

Читать дальше