He had asked how he was doing. The man grunted “good.” My father asked him his name. The man pulled open his wallet and took out a laminated card.

“And he showed me his name,” my father said, setting down his fork.

We had gone to Our Lady of Grace that morning. I silenced myself before the silence. The kneelers hurt my knees. The Eucharist was blessed and families crawled over me through the pew on their way to receive it.

The last girl’s hair brushed my face. She steadied herself on my knee.

I was a believer in transit. All service, my father twitched in his anxieties, shifting his weight from thigh to thigh. He was trying to understand the great nothingness of God. I believed in the great everythingness of me.

I am named after the place I’m from. It’s a lot of fog and smokestacks. Trailers parked in mud and dog shit. The roads circle places you don’t want to be. We had left the Chinese restaurant. The subject changed in the car to Christ.

“The man spoke in riddles,” Dad said, “for ears that could hear.”

Leafless trees dripped water and there was a war somewhere. The onions gave me indigestion, and this year the ladybugs were bad. Dad would vacuum them off the windowsills.

Posters on the campus I went to had asked me if Jesus was a Republican. The campus was far from the place I’m from. It was cleaner, more cluttered, full of people who knew enough about God to say he’s on their side. I spent my time there alone. Some days Dad called and said he hadn’t spoken to anyone all day. Birds pecked at the brown grass outside my apartment window.

“That happens to me, too,” I would say.

It was spring break and rain fell slow most days that week, melting mounds of dirty ice at the edges of parking lots and driveways. Our street stretched into the woods and each driveway had its own name. Smoke rose from a row of off-white houses.

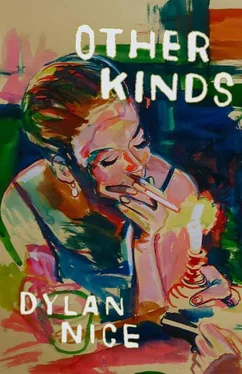

I painted in my bedroom. The same canvases over and over. I tried to paint a vision I had. I was a little boy and I was in a field looking up. And up there, the sky was gray and an airplane was taking off. The plane seemed to be everything. It wasn’t flying away, or leaving me alone.

That night there was a girl I was in love with. I wore a nice sweater and smoked in the car driving to her house. I had made a CD and labeled it Tonight and played it, thinking there were chord progressions that sounded like whatever it was I was pursuing.

I took her for a long drive to a barn where a band played in the cold. Couches full of cigarette burns surrounded the stage. I usually went there alone because I knew the people but didn’t have to speak.

“Not how you remember?” I asked her.

We got in my car and drove. We rode through no-streetlight towns and talked about leaving.

“I’ll miss these spaces,” I said.

“I like the distances,” she said. “Everything just stretches out.”

Mornings were the worst for her; she told me she woke feeling thick and still thinking about the things that had kept her up. Her father was on disability but she didn’t say why. I had once seen him jogging. There was no one else.

“I keep him calm,” she said.

She fixed her hair and her unbuttoned cuffs fell away from her wrists. They looked thin enough to break. A high school basketball game was letting out and we followed behind a line of slowing red lights. Orange mixed with white and through the dark. I put my hand on her knee. Her name was Laurel.

That night I lay in bed while blinking red dots passed my window. As I child, I had imagined whole wars raging just out of sight, and my house rose from the violence as something sacred. My room jutted above the trees and hills. Out there men were dying and it was fine because they were just men and I was a little boy.

The staleness of my house would lead me to the windows. I smeared the yard’s colors through the bubbled glass. Things then were not substance, but the beauty children hide from the bones of adulthood.

Laurel had worn silver earrings that hung with her blonde hair. Her voice sounded better at night. From that I saw images of her in dresses on the deck of a ship — in jeans on the ice. She was the things I couldn’t paint.

Her house was much like my father’s: Spartan, bookish. Her father kept the sink empty; the walls were painted woodpanel and bare. She led me into her room where the colors were darker. Vinyl album covers were hung on red walls and she dropped the needle on her suitcase turntable. A Celtic folk song played and she lay across her bed.

“This is where I keep myself,” she said.

I edged my shoulder near hers but felt like her brother.

“It’s the first place I would have looked,” I said.

I rested my cheek flat against the green spread and saw two guitar cases in the corner.

She said she would have looked for me in sawmills or strip mines, or the clearing where our friends melted green bottles in the campfire. I said I could take her there. It would do her good to go.

“You could see what you aren’t,” I said.

She played for me later; her voice was dark and curled. Her fingers slid down the strings. I couldn’t touch her. I didn’t put my hands on her.

I went there alone that night, down the dirt road behind the power substation. There I saw the people I expected.

Vaughns and Pollacks, at least four Keiths, and one Wojtovich. They asked me what I was up to and told me where they were working now. Some of them still wore letterman jackets and smoked the brand of cigarettes I had bummed off them in the car before school. Work had hardened their voices.

“Getting any pussy?” one said.

“Yeah, yeah, as much as you,” I said, and kicked shale off the top of the dirt toward the fire.

I said nothing about Laurel — I was too upset that she existed. I spoke little and soaked in the cold.

My father called and I lied about where I was. He said he was calling just to chat, said we needed to get together again before I went back.

“Church, again,” I said.

“Saturday night vigil,” Dad said.

We burned candles and people looked spiritual in the soft light. A brunette in a black blouse sang about how she couldn’t keep from singing. The only words I took away were “happy fault.”

My father rocked in his pew. He breathed heavily and swayed. I wanted to grab him and tell him he could stop. That this was OK.

God and no God. Girl and no girl. And all here nameless.

The homily began and I wanted to tell my father that part of me had been crying in the Chinese restaurant, too. I looked out past the combed heads to the bleeding man hanging below a crown.

I took hold of my father’s shoulder and leaned him back.

“Be still,” I said, unable to look at him. The couple in front of us nudged together, turning back slightly.

“No one is watching,” I said.

Before the rain started, we got into her car and I sat in the smell of her perfume. A spray, one of those bottles of beauty suburbia affords its daughters. We drove through the sparse end of town past the ice cream shop she liked.

She wanted to go to the card store even when the long days stretched without holiday. The parking lot smelled like heat and gasoline and the threat of rain. Inside, I listened to a card that played garbled country music. She giggled at one with a picture of a roller coaster that read, “You’re my favorite amusement.” She walked the aisles and talked about learning more about herself and staying close to home. Home was a scattering of coal company houses in the Allegheny Mountains.

She was soft and when I felt her I thought of words like “mild” or “macaroni salad.” All summer her mother set heavy salads out on the picnic table on Sundays. Eggs covered in mayonnaise. It tasted just enough not to taste bad.

Читать дальше