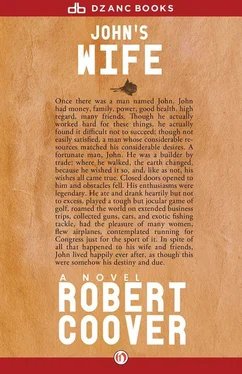

Robert Coover - John's Wife

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Coover - John's Wife» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2014, ISBN: 2014, Издательство: Dzanc Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:John's Wife

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dzanc Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2014

- ISBN:9781453296738

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

John's Wife: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «John's Wife»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

John's Wife — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «John's Wife», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

News of the sudden violent death of the French penpal, the one who had upstaged and jinxed Daphne at the wedding four years before, reached town by way of Oxford’s boy Cornell, back home from his educational graduation trip abroad in a state bordering on severe shell shock, such that the news itself was rather minimal and had to be imagined, or as Ellsworth, whose task it was to accomplish this feat week after week for the readers of The Town Crier would say, recreated. Selectively recreated, for there was news, intriguing as it might be in oral form, that did not suit the printed pages of the town’s weekly newspaper, the widely rumored events out at the Country Tavern during Marie-Claire’s visit to town the month before just one example, an episode referred to only obliquely in her obituary a few weeks later when Ellsworth wrote that the deceased was known for her “passionate zest for life and happiness, so typical of the natives of that great enlightened nation, and not always understood by simpler, more straightforward prairie folk.” That got him in a bit of trouble with the locals actually, but Ellsworth brushed it aside in his usual lofty manner, remarking to his friend Gordon, who had mentioned some of the complaints he had heard, that, suffocating as he was in the bloated provincial crassitude of this bumpkin town, he felt obliged to put the needle in from time to time, simply to survive. Ellsworth’s sympathies were perhaps affected by the fact that he was at this time hoping to season his own existence with a touch of French zest, his ancient dreams of the bohemian life having been revived that summer when his photographer friend suddenly took in a live model, a pretty little uninhibited gamine from the trailer camp. Ellsworth, foreseeing the delightful possibility of an old-fashioned beaux-arts ménage à trois, as Marie-Claire herself might have put it, once again took to wearing his beret and a kerchief tied round his neck (it was still too hot for the cape) and began paying regular visits to Gordon’s studio, having assisted in previous photo sessions and, for the sake of art and friendship, offering to do so again. Gordon, however, was less generous with Pauline than he had been with his mother, may she rest in peace, and did not seem enthusiastic about Ellsworth’s suggested new arrangements, which caused a certain distance to grow up between the two men for a time, though Gordon did show Ellsworth a few of his photos of the girl and asked him to witness his marriage to her the following year. About all Ellsworth got out of the whole affair was a paragraph for his novel-in-progress (at that time, several years before the crisis provoked by the death of the car dealer’s wife, a novel with only one character and as yet untitled, though perhaps to be called The Artist’s Ordeal ), an aesthetic meditation on the teleology of models, which he read aloud at a meeting of the Literary Society at the public library (only John’s wife understood in the least his artistic intentions, he read for her alone) and then abandoned, the larger project as well, and not for the first time. At times, Ellsworth stepped forth onto the international stage to accept the world’s accolades for his innovatively designed yet classically structured masterpiece of creative fiction, and at other times he recognized that he had only managed to write about fourteen pages and probably only three of those were keepers, and gave it up. His journalistic recreation of the final hours of the French artist-friend of John and his wife, his primary sources being either incoherent or inaccessible, he also abandoned, limiting himself in the end to a brief obituary which remarked on the “shock and sorrow that rippled throughout our community when the tragic news, like a thrown stone, fell upon it,” and an “I Remember” column supplied graciously by John’s wife and published a few months later.

The suicide of Marie-Claire surprised many in town, perhaps even his wife, but not John. Marie-Claire was not strung together for a long life, John knew, something was bound to snap. He knew, too, he had had a part in it, he and hinky-dinky, but as usual John, whom some blessed and some did not, had no regrets. It would be like regretting the way the cosmos worked. If anything, he felt a vague sense of relief. Sex with Marie-Claire was like grappling with a wild thing: there could not be two survivors, something had to die. And, finally, John being who he was, it was her turn. Which was Bruce’s take on it as well, she having become their paradigmatic heroine of all such stories. One of Marie-Claire’s lovers, a young art student she’d known prior to Yale, had thrown himself under the Metro before her very eyes, and she had driven a married man, a friend of her father’s, completely mad. A psychiatrist, if the story could be entirely believed, not always the case, for even melodrama Marie-Claire melodramatized. These were the ones he knew about, no doubt there were other casualties in Marie-Claire’s passion wars, not including the ones he and Bruce had made up. Even Yale’s death, apparently so remote, seemed to John linked somehow to the way love and death got fused in that crazy furnace inside her, and indeed Yale’s last letters, sent from the combat zone, hinted at his own awareness of such a connection. He spoke not of “death’s embrace,” but of “embracing death,” as though it were some sort of compulsion (though his imperfect French might have been at fault here), and he described his army patrol’s search-and-destroy missions into the jungle’s “perilously erotic hot green thighs” as “lustful plunges into sweet extinction.” Of course, Yale always did relish the double entendre, all that may have been, even if a bit dark, just a joke. As was hinky-dinky at first. Apparently, at their wedding reception, the old Ford dealer had recited some verses from “Mademoiselle from Armentières” to Marie-Claire. Probably his idea of being friendly to a foreign visitor. All she could remember, as she told John and his wife one night in a Paris bistro during their second honeymoon three years later (they had just come from watching a troupe of “Troglodytes” perform a “Scène d’amour” in the airless underground cabaret beneath their garret flat), was something about four wheels and a truck — John could easily supply the missing rhyme — and the refrain line which, she said, had been puzzling her ever since. “Wut ees hainqui-dainqui?” she asked, smiling her mischievous smile. “Ees like hainqui-painqui?” “It’s the same thing,” laughed John, squeezing his wife’s hand beside him, “only you use your dinky, not your pinky.” Two days later, his wife went shopping for presents for their two sets of parents back home, planning to meet Marie-Claire at a gallery cafe in Saint-Germain-des-Prés for lunch, and an hour before that luncheon date, Marie-Claire turned up at the garret, where John, in his briefs, was shaving at the paint-stained sink. This in itself was not unusual. Marie-Claire often turned up, unannounced, at odd moments. Whenever she did, she always seemed to need to use the facilities, squatting quickly there behind the refrigerator, chattering gaily all the while over the splash of her pee, her head peeking out around the refrigerator door, telling them about things that had happened to her on the way over, a bit earthy, yet quite delicate, too, something John knew he could never carry off, he was very impressed. On this occasion, however, she stepped up behind him at the sink, ran her hands into his briefs as though crawling into the cellar, and, her smoldering dark eyes reflected in the scalloped mirror over his bare shoulder, whispered: “I am so lonely, dear Zhahn. Yell, he ees so far. May you help me? I am so much needing ze … ze hainqui-dainqui… Parlez-vous?” And so it became a kind of gentle joke between them, and a kind of bond, and when the news came through a couple of days later about Yale’s death in action, that bond was, in tears and frenzy, hotly yet somehow mournfully sealed, and thus Marie-Claire’s unhappy fate as well, forging thereby in John’s mind an indelible link between horror and compassion, compassion and horror.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «John's Wife»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «John's Wife» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «John's Wife» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.