“Shit,” said Casey, and swerved around a pothole.

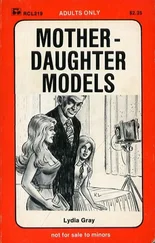

It was the private room in her house, it was Bluebeard’s locked closet — the only space, since the accident, where she was not only a dutiful mother or wife. Say what you liked about husbands: mother, now there was a role that typecast you for the rest of your days. . being a slut was a survival tactic. No more, no less — that sly, indulgent freedom, that liberty in its rotten deceit, the sweetness in the rot. It had saved her from despair more than once.

When she was young she’d been pedantic on the subject: monogamy was authoritarian, a form of property law. On occasion she’d even tried to convince Hal, who had a more conventional mindset. There had been long earnest nights of conversation, now blurred in retrospect — one ego struggling to free itself from the encumbrance of another. Since then she’d dropped all that as a series of rationalizations. Arguments could be made, but at its base sleeping with many men who were not her husband was a pure satisfaction, an expression of greed and vanity, a glorification of herself. She could freely admit it; she did. In those spans of time, sleeping with other men, she emerged from obscurity into the light. She was the subject of the biopic: the camera followed her face, thus slowing time, and a score accompanied her movements. She liked to see herself with others; she wanted to be known.

And Casey, in the wheelchair, how could she make that gesture? It was the wrong kind of freedom for Casey, it was a category error. Yet here was Casey, willful as always, stubbornly ignoring the fact that her gesture was compromised. Yes, yes, this was the manner of her revolt — it was parallel — Susan saw that now. The two of them were the same in this, though Casey had no idea.

But Casey could not walk. She could not walk and had no legs that moved.

Poor darling, poor sweetie.

Possibly this 1-900 thing was a way of keeping her leglessness private. Callers would never know that she was in a chair, so Casey could be pure voice — could gratify them in the warm and electronic darkness, the dark that bristled with mystery. Their private and dirty handmaiden.

Casey was always, always breaking her mother’s heart — Susan had learned to withstand the familiar, crushing pressure. She’d been forced to. This was only the newest and latest erosion of her hopes and dreams. Now she was forced to see a stark outline: her daughter as a phone-sex drone. Well, yes. Of course. It was the logical next step. Casey had already done the rest — done the apathy, done the rebellion, done the resentment and the self-loathing. Now, apparently, it was high time for the paraplegic sex work.

Susan could squint and make out the stereotypes of those outlines — archetypes, stereotypes that shone with depressing implications.

Gooseflesh crept up her arms.

“You told your father this?’ she pressed after a minute, shaking her head. “And you didn’t tell me?”

“I didn’t tell him, actually,” said Casey. “He figured it out. He just knew.”

“He just knew ?” It was embarrassing. She hated to get teary in front of her daughter, who would shoot her a familiar filial look that neatly blended compassion with contempt. “But it’s Hal . He never just knows anything.”

“Don’t be a bitch.”

Susan shook her head. Her throat was closing.

The car was a cage — how did people not always think so? Cages on the assembly line, metal cages with bars and glass, cages along the roads by the billions with their tailpipes shooting out poisons. After the accident she thought of all cars as her enemies, thought viciously that she hated all of them for what they’d done to Casey, hated them like animate creatures, maggots or weevils or scorpions, and she would kill them all if she could. Not KILL YOUR TELEVISION; kill the cars. But of course, she also had one of her own and drove it all the time.

Cars were the life, here in L.A. Cars were the smallest and most portable of all homes. Even Casey, almost killed by a car, still lived in them without obvious reflection.

She felt for the vinyl shelf along the side of the door, pressing down with her elbow. There was a narrow well, half lined with lint, on the blue armrest, and she looked into it studiously. The lint blurred. What did they make these oddly shaped holes in the armrests for? What was supposed to fit there? Nothing fit. Or if it did, it was unknown, illusive, and not part of life at all.

The holes were useless, and these useless holes were irritants, ever-present, inexplicable, angering.

“He heard something, is all,” said Casey, more kindly. “He overheard me talking to a friend.”

“You wanted to be a professor,” said Susan. “Remember?”

She was still shaking her head, minutely. It was almost involuntary. She wiped the corner of one eye quickly with the heel of her right hand and insisted on staring out the window.

“You wanted to get a Ph.D,” she went on.

“Now, that was just stupid of me,” said Casey.

They were on the road into LAX now. Taxis and cars lined up at the curb to their right.

“You were going to improve your French.”

“I was i-di- o -tic.”

“You were going to go to graduate school.”

“I was eighteen! And now I’m not anymore. And I don’t want to be some boring academic. Even if I could. It’s not the chair, Mother. It’s just me. It’s like, a natural evolution.”

“So you evolved from a Ph.D. candidate into a phone-sex worker?”

“I evolved from a teenager to a grownup.”

“But you’re more,” said Susan.

“Jesus. It’s not the end of the world, OK?” said Casey. “Chill out. Take a deep breath. It’s just a job.”

She spun the wheel into the parking structure.

•

At the baggage claim carousel they waited awkwardly. Susan watched her daughter’s face, the lashes shading the cheekbones. She had not always been so slight and wan. Before the chair she had often been tanned, cheeks flushed, hair lightened by the sun. She had a boyfriend who surfed and then one who was a skateboarder; on weekends they disappeared down the beach in sneakers and ratty, faded shorts and came home with peeling noses and salt tangling their hair.

Now she was always pale. But she was still beautiful. In her mind’s eye Susan saw baby pictures.

God damn it. Stay presentable.

“You actually choose to do this?” she started, over the background murmur punctuated by loudspeaker announcements. “Because if it’s money—”

“I choose,” said Casey firmly.

Susan stared past her at a poster of a hotel: a white high-rise with looming palms in the foreground. She stared at the high-rise. She stared at the palms.

Casey caught sight of him first, coming toward them in ragged pants and shirtsleeves. He was thin and too darkly tanned, like a Florida retiree, but lacking the beard Hal had described. A recent shave had left the sides of his face paler than the rest, the lower cheeks and the chin.

But what alarmed her was his expression — heavy, anxious. He bent over Casey first, knelt down at the chair and took her face in his hands. Susan saw how she looked at him, noticed it fleetingly, but then already — in the shock of this — the recognition faded as he stood up straight again, still holding Casey’s wrist.

“I’m sorry, but I couldn’t tell you this over the phone. I have very bad news,” he said.

In an instant the whole of existence could go from familiar to alien; all it took was one event in your personal life. You might think you were only a mass of particles in the rest of everything, a mass exchanging itself, bit by bit, with other masses, but then you were blindsided and all you knew was the numbness of separation.

Читать дальше