“Now where the hell is that Chip?” he said to himself as he got out of the truck.

“Yo, Sam. Yo, Chief. Morning,” he called as he walked toward them. “Now where the hell is that Chip, you think?”

“Chip here,” the Chief said.

“Oh yeah? Where?” said Earl.

“I’m here, ma man, I’m here!” came a voice from over by Earl’s truck. “Here I come.” And a young man of about eighteen, very scrawny and tan with close-cropped dark hair, started a slow and crooked walk toward the threesome at the park bench.

“That was somethin’, I mean, that was some action Earl! I mean, that was definitely not on my agenda. I wonder can you dig it? Came right up to my leg then; stopped on a dime. Too much! ‘Student crushed by pickup at Seaview Links.’ What a routine that was …”

“Fucked up,” Sammy murmured.

“Made the turn — the avenging angel — spacy day — whose thoughts were elsewhere — young boy asnooze watching the eyelid light show — mysterious tires crunching in gravel — stopped on a dime. What a scenario! — Hey, Chiefie! what’s happening? Hey Sam! What’s up for today, Earl? Do we plant trees? Do a little, you know, green care?” He danced a little jig. “I can dig it! — reprieve from death!”

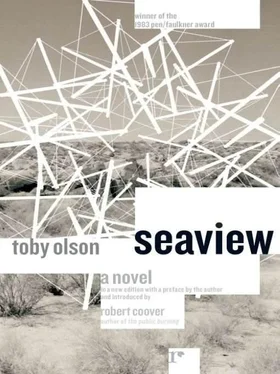

“Most definitely fucked up again,” Sammy said. And Earl, with Chip loping behind him, walked toward the parked machines on the far side of the clubhouse. Earl was the greens keeper at Seaview. Chip, a horticulture student at Cape Tech, was his helper. Sammy was the club manager and pro. Chief Wingfoot believed he owned the golf course.

BY THE TIME IT WAS SEVEN O’CLOCK, CHAIR FREDRICKS had showered and shaved, carefully cleaned, cut, and filed his fingernails, shined his golf shoes, laid his golf clothes across his bed, broken open a three-pack of Top Flights and put them in the zipper compartment of his plaid bag, put up the coffee to perk on the Sears workbench in the basement, and was now standing in front of a hot cup of it, looking out at the wheel cover of his new Oldsmobile, framed in the basement window. The cup and saucer were bone china, with blue flowers on them; the coffee was black and hot; the wheel cover was clean and shining, because he kept it that way. It was a beautiful morning in town, and in the yard of his accounting office in the front of the house, a couple of mockingbirds were showing off. The Chair was dressed in a short blue robe. His woods rested beside the coffee cup on the workbench, and as he lifted the driver up and began to clean the head’s grooves with a small silver pick, he was thinking about the difficulties with the Quahog People and what he hoped the day would bring to him. When he finished picking the flecks of dirt out of the grooves, he put the shaft of the driver in the small vise attached to the bench, sprayed a little polish on the head, and began buffing it with a clean white rag.

As chairman of the golf commission at Seaview, all communication with the Quahog People fell to him. It was not the kind of thing he had bargained for when he had politicked for the position five years ago. What he had wanted was to keep the operations of the course professional, and he had thought of his only major adversary there as Sammy. Now these Indians were writing him letters and calling him up. They usually called him when he was at work on somebody’s books or with a client. He kept telling them that he, as chairman, had nothing to do with their claim of ownership; the course was run by the National Seashore, only leased to the town, and they would have to deal with the Seashore Commission. But every time one of them called or wrote, it was a different one. They seemed to have no leader, and he kept having to repeat himself. And then there was this Frank Bumpus person; for two years now he had hung around the course. He was not good for the professionalism of the place, and being an Indian, though he never mentioned or did a thing about it, he must have been connected with the Quahog People. The rest of the golf commission members were all too happy to let this business fall to the Chair, and since the Chair would not have trusted anyone else with it anyway, the hassle was all his.

He finished buffing his driver and reached for another club. He could hear his wife stirring upstairs. He put the club shaft in the vise, took another sip of coffee, and began to pick. Well, to hell with the Quahog People, the Chair thought. This is a more important day. It was the day of the first major Saturday tournament of the season. All the others had been tune-ups and haphazardly run by Sammy. The Chair favored these early, official tournaments, the ones that were for members only. The members rule kept most of the tourists out, and most of the players were locals. The Chair knew their ways and could keep things in line. More important, he was set this year to get Sammy, and he was going to start things off right this season by beating him. He kept buffing at the club heads until the luster came up the way he liked it.

BY TEN O’CLOCK IN THE MORNING, CHIP WAS WELL INTO the swing of things. At nine, in the bathroom in the clubhouse, he had snorted a line of coke, using a clear plastic ball-point pen with the inkholder removed. That, on top of the joint he had smoked around seven-thirty, had done the job. Now he was rambling down the second fairway on the mower, aiming for the second green in the far corner of the golf course.

“Out of sight of them all, ha ha!” he said to himself in the mower’s hum. He stopped short of the green and turned the mower off. He could hear the dull grind of Earl on the fairway mower on the other side of the course. He got off his machine, took a look up the fairway behind him, then turned his attention to the task at hand.

The second hole at Seaview was a par-five, five-hundred-and-ten-yard hole, with a dog leg to the left. The tee was cut at the top of a hill, with a heavy rough in front of it running down about seventy-five yards to the beginning of the fairway. The fairway before the dog leg was wide open. There was a large trap to the left, on a knoll from which the ground ran down to an open area just at the dog-leg knee. The open space was where the average hitter aimed to drop his drive. From that point, the fairway turned and narrowed a little, with heavy rough running up a hill to the left and pine trees run-ning up a steeper hill on the right. At the end was the untrapped green, of average size, closely guarded in the back by low pine and scrub running up yet another, gradual hill and toward the cliff, high at the sea’s edge, about a hundred yards away.

From the tee one could see the edge of the green in the distance. A strong shot could leave the hitter under a hundred and eighty yards to the green. It was possible to get home in two. From the tee, looking up to the top of the hill that bordered the narrower part of the fairway to the right, were three massive radar domes. They looked very much like golf balls and were the property of the Seaview Air Force Station, a lookout command on the edge of the Atlantic down the coast from the lighthouse. Below the radar domes, about halfway up the hill, was a small, medieval-looking stone tower. It was called the Jenny Lind tower and had been given the name by the man who bought it when the old Fitchburg Depot in Boston had been demolished around the turn of the century. The story was that he had heard Jenny Lind sing from the tower, had fallen in love with her and had put the tower up on land he owned at the time as a tribute to his impossible dream.

The second was Chip’s favorite hole, and when he had made his “Special Seaview Map” it had gotten the most detail and attention. He liked riding the narrow fairway on his mower, the way the slopes on either side guarded it. In late July, he liked to climb up the hill and sit close to the tower, eating blueberries he had picked on the slope out of his hat, watching the golfers try for the green. The fairways at Seaview, all but the eighth, were hardpan and sand, with little grass, and he liked to watch the golfers duff their shots, yell down the cavern of the fairway, throw their clubs, and stomp their feet. They never knew he was there watching them. More than any of this, he liked the apron, the collar, and the green. He had worked hard, removing small stones and large ones, filling and level-ing with fresh soil, planting what he could get to grow, cutting things to just the right length.

Читать дальше