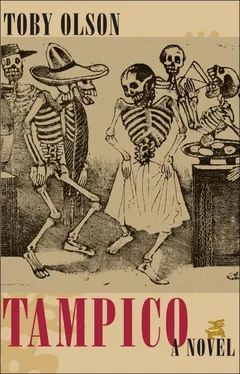

In the dances of skeletons, the parodies lie in activities and the broad, yet subtle, exaggerations these figures in their bones bring to them. Risen up from the dead well after their moldering, calaveras partake of the same world that got them there. But in the common anonymity of their figures, clothed always in uniforms — even a house dress is that — thrust this world into example and instance, and thus celebration, of both the menial and significant, rendering the poses of both ludicrous through gesture and tableau. Women are men, and children are only smaller versions of women and men, and only by virtue of action in tasks or bending to pantomime in mute conversation are the bones expressive, though a jaw might creak up a fraction at the corners, the subtle hint of a thought that provokes a particular grin that never comes. And this is the art of the dead come alive, and within it the recognition that everything is a story.

And in these stories all calaveras have their parts, from the politician vomiting words out over the crowd, to the culpable businessman at his elbow and the henchman at the platform’s edge. And each in the crowd too is an actor, in gesture of agreement or of disgust, varieties of pantomime, and the raising of weapons in the bony hands of the military at the periphery. And yet among them, on rare occasion, in the figure of a foot soldier, a carpenter, provocative virgin to the side of a gathering of virgins, one finds the empty skull gaze, the figure in ambiguous gesture beyond the story, head tilted in longing toward the might have been. These are the traveling calaveras , and whether they are few or many is not certain, for one may see the same one seen before without knowing it because of the traveling, that search for a proper circumstance in which the dance can be mindlessly entered, which is never found, because the skeleton is the free essence beyond longing or nostalgia, and these are the aberrant calaveras , dragging the memory of the flesh and desire with them.

Two children, a boy and a girl who were farm children. They passed through a dark wood on their way home, and at a bend in the trail in the wood they came upon a fallen oak tree and a calavera sitting on the trunk among branches, and they were not hesitant because they were children and had no fear of death. The calavera wore the uniform of his last engagement, the vestments of a bishop who had sold the votes of his diocese for money. His grinning skull face stared out from the folds of his robes, his head cocked arrogantly to the side in remembered gesture, but there was a certain look of longing in his teeth and hollow eyes that the children noticed immediately as they climbed among the branches to sit beside him. Are you lost? they asked. He said he was, but he was grinning, and they were not sure of the meaning of his answer. They could see his bare clavicles where his garment opened at the neck, and they thought he must be cold wearing only his bones under his clothing, and they reached up to raise the hood of his cloak over his head, and it fell down to cover most of his face, guarding against any clear view of it. They helped him to climb free of the branches, and then they walked beside him, holding the bones of his fingers, as they led him home.

It was a farmer’s home, one room with a large wooden table and a stove and sink and a stone fireplace. There was a double bed in a corner and pallets on the floor, and the mother fell back at the sight of the bishop in the doorway, flustered and honored, and led him to the table and put food and drink before him that he could not eat. He said he just needed a little rest, and she placed a chair near a window, and the calavera sat in it, and the children gathered on the floor at his feet. And once he’d answered the few halting questions the mother put to him, she went about her business of cleaning and cooking, and he sat still in the chair in his spectral garments, watching her.

Then, at day’s end, the farmer came home from his labors. He held the children up in his arms and kissed his wife and bowed to the bishop. Then candles were lit, and the family took up the routinized activities of their evening. All was action and gestures of interchange, and the calavera thought of the possibilities of exaggeration as he watched them and thought nothing of the next leg of his journey, the search for that future circumstance in which he might find his place.

The woman was at the stove baking. The farmer had lifted a block of wood and was carving the face of a man into it, shavings cast in the fire, and the children sat on the floor, a few feet from the fake bishop’s hem, fitting paper clothing on small anonymous figures. All faces were lit in the wavers of candlelight, and the calavera watched them dissolve and reconstruct as heads turned on their axes and words drifted in lazy half sentences across the room. And in a moment of silence he saw the mother’s face pause in its animation, her hands sunk deeply in dough. She was looking out the window and her gaze was vacant where it met the glass, and the calavera was stunned to see that same look of longing in life that he was aware of in his own face in death, and he recognized it was an avenue of possibility that she was looking down. It was as if between her and the window were actions and the meaningful assumption of actions, but at the glass itself was nothing, just her desire for a place beyond where the terms of her longing ended. And when he saw the same vacant look in the farmer’s face, as he glanced down to the floor in his whittling, he found he was seeing into the human condition with a new understanding. He sat in his robes in the chair watching its manifestations as he mulled it over in his mind. He thought of life as a central artery, running parallel to the spine, and each vein and capillary, extending out along bone to the exuberant extremities, as those possibilities of alternative bloody avenues down which one might glance but never go. He thought of his own life, before he was a calavera , and its necessarily stunted quality, though it had been a life of satisfaction and fullness, and he had walked its broad and easy causeway free of any care.

He’d been a journalist, this calavera , privy to the hidden corruptions of government, present at the forefront of shipwreck and devastating fire. On his bicycle he’d ridden to the brink of individual illness and family difficulty, often into circumstances of possibility where he might have stepped from the saddle into another life. He’d seen a boy he’d desired, saved from the roots of a tree. He’d seen women whose lives were frustration, wife, daughter and nun. Each had been ripe for engagement, but he had simply written their stories and moved on, life’s longing recorder. Now his bones shook under his bishop’s garment as he silently articulated his proposal.

All men and women long for the might have been, those avenues of life they didn’t take, and in the recognition that each one was a possibility, held in the memory as vision grown hazy at terminals beyond all bright beginnings, longing becomes empty nostalgia as the veins dry and collapse along the bones and the broad gestures of the body wither at the outer reaches. Devoid of the animation of living, all come narrowed and regretful to their deaths, since of the many possible lives, only one was lived.

He saw it in the look of the farmer’s wife and in the farmer, and though the children glanced up from their play and down those first narrow byways only with bright eyes and curiosity, he knew their time too would come.

And he knew now that the living he’d longed for again as a calavera held its own profound longing, and that when he reached a new circumstance the force of his look would be doubled in the intensity of its longing, drawing the eyes of the viewers to a bloody familiarity, and would overwhelm the dry extravagance of the dancing bones.

Читать дальше