“The Indians have pale faces,” Carlos said, and when the movie was over we went to bed.

In the morning I got up late and went out to the car to check the odometer, then walked back into my new office to write things down. I’d call the lawyer in Providence the next day, give him the complete picture on Erica Plummer and the name of her motel. It would take him some time to get the court order, but he’d be quick about it once he heard the story from her own mouth. I’d worked with him before, always against him actually, when I was on the force. He’d kept us on our toes, getting more than one offender off because of faults in procedure. He was efficient and tough-minded, utterly fair, and I was pleased to be on the same side of the table as he was now.

I heard Carlos in the kitchen as I was finishing up, and when I got there he was sitting in a chair with a pot in his lap, trimming the ends off the wax beans, and the turkey was sitting in the black roaster on the table.

“Room temperature,” he said, and I went to the refrigerator and got out the sweet and white potatoes and took them to the sink for washing.

We had the turkey in the oven by two-thirty. It was a small bird, though big enough and there’d be leftovers, and once we’d heard the pops and crackles and had basted it, we decided on a short Thanksgiving walk on the beach, just an hour, then we could return and finish the preparations and set the table. I had two bottles of good Chablis in the refrigerator and we’d drink a little Irish before sitting down.

“Around five?” Carlos said, which sounded right to me.

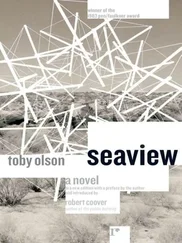

The sun was already sinking behind us when we stepped from the parking lot and down to the empty beach at Herring Cove. The tide was out and the beach was broad and the sky over it had cleared of clouds, and there was light in the water, a last pink wash, and we saw it in the bodies of a few gulls riding the swells beyond the foam of the first breakers.

“The sea,” Carlos said. “Unlike the bay. That was like Mexico, but not as much life.”

“You mean at Strickland’s house.”

We’d walked down to the quiet surf and I’d picked up a stick, a barrel stave worn white by salt and sand. Pipers rushed to the edge of receding waves, then raced away.

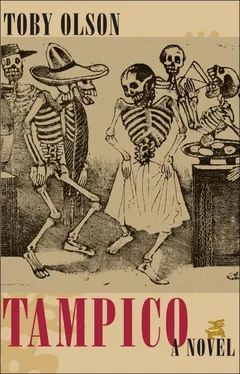

“In Mexico,” Carlos said. “Before we left Tampico. There were men-of-war, and those transparent sticky ones, and you could see the fins of ribbonfish caught in pools when the tide was out.”

“When was that?”

“In ’60,” he said. “I’d place it there. Wouldn’t that make me thirteen? Something like that.”

“And then you left,” I said.

“That’s right.”

“I’ve been thinking about the time of my leaving too,” I said.

“To put something dramatic on it?”

“I guess so. I haven’t really felt it yet, so I think about it. A certain feeling?”

“You could talk to someone,” Carlos said. “A community feeling. There are such things.”

“Maybe I will,” I said.

But I couldn’t think anymore. The sun was behind the dunes now and the sea was awash in pink all the way to horizon, and when the gulls rose up from the pink sea their bodies were white, but their wings were red and their tails were fans, rosy and translucent at the tips.

“That’s something,” Carlos said. “I never saw that in Mexico.”

The table was covered with a white cloth, and there were candles near both ends and the light flickered in the wine. The turkey sat on a yellow platter in the center, not golden, but the color of a light wet mahogany, the tips of its ankle bones gathered in rosettes of foil, and at its left, in a round white casserole, the orange sweet potatoes were hidden under a field of melting marshmallows stained with caramelized brown sugar and a pattern of roasted almonds, and on its right was another bowl, the mashed potatoes, butter melting and flowing among its craters. The black olives were black pearls spilled from a string, and some sat in a row in a green boat of celery, a few fluted blossoms left at the end, and the pearled onions were pearls or caviar from a monstrous fish still held in the birth fluid that was a light cream sauce. The corn was corn. The tomatoes were green and red, and the wax beans were lime, laid out in rows like small loosened faggots on a shallow ceramic boat fashioned to look like wax beans, though slightly darker ones, and stuffing erupted from the turkey’s cavity, a large silver spoon embedded in it, its handle active in flickers of candlelight, ready for the taking.

It was five o’clock and dark outside, and we sat in the kitchen. The table was small enough to reach across, but we spoke somewhat formally for the occasion and didn’t reach and passed the plates and the bowls and wine, smiling and nodding to each other over the turkey and around the tapers, and when we were finished we filled our glasses again and picked at the food. There was plenty left for the next day and maybe even the next.

His mother died in a fire in Matamoros when he was just fourteen years old. It was a house fire, but the interior walls of the house had been torn away in order to make a large sewing room, and other women had died too at machines there, and some had died after leaping out of windows, their twisted bodies and exposed bones in billows of black smoke, blood soaking into the dirt street and their thin flowered dresses.

His father had brought them north a year earlier, talk of work at the border, but it was steady work for his mother only, and the odd jobs his father managed to find were an insult to him, a man with no Mexican in his face at all. “He looked like a gringo, but he put a veil over his past entirely and I don’t know his sources, but that he was adopted and that the people who had raised him were long dead. And then my mother died in the fire and my father left, went over the border illegally, and I never saw him again. Then I crossed over too. I was just fourteen, and it took me ten years and a little help to become a citizen.”

He’d crossed the United States, then wandered back again, and in the course of his years of travel he’d worked at many menial jobs, then had found a good man who had taught him carpentry and house repair, then a few jobs as a handyman and some where he was a resident, once at a large ranch in New Mexico, another at a resort in the Catskill Mountains, a year of tenure in which he repaired the ramshackle dormitories of the transient waitresses and kitchen help. There were holes in his story, years vacant and unaccounted for, and I kept feeling that he, like his father, held up a veil of privacy, lest I learn too much and get to know him.

It had all been a constant leaving and arrival, vague feelings of regret and anticipation, and after a while those had dulled for him, as well as the little moments of anxiety in uncertainty between places, and he told me of the solace he’d taken in reading and mastery in woodwork and diagnosis in electrical and plumbing problems, worlds he could take with him that remained constant. He had a bag of tools and he left books behind him and acquired new ones, and in a while he was closed off in himself, and then he came to the Cape and found his place with Strickland.

I reached across the table to fill his glass, wanting more, some glue of narrative.

“What about the war? Vietnam, I mean.”

“I was in Chicago when things got cooking. So I left. I was never bothered about the draft. I just kept moving, and the work was mostly cash, you know. Very few records, and no social security.”

“How old was Strickland?”

“Forty-five,” he said. “Two years older than I.”

“Me too,” I said. “I mean, I’m forty-three.”

“In a fire. Like my mother. I believe he must have been an excellent pilot.”

Читать дальше