And the old men were the young men in the stories, and the women too, putting it off in reconstruction, just as I had in the certain knowledge that my house was stable.

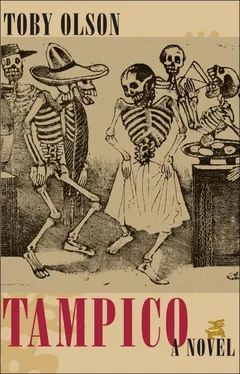

But the earth was shifting now, and the calaveras might soon be dancing, in the Manor, in the figure of the fascinating man behind the curtain, down under the lighthouse. And I wondered if the time would come that I might join them, free of the house and my mother and the Manor. I wondered if I too might dance, in the meadow, out of sight of the sea and the image of that park in Tampico, my agora and the beginning of my travail.

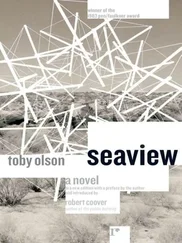

He was traveling again and it was close in the truck’s rattling cab, and through the splatters of dead bugs on the windshield he could see the live ones coming in a hazy veil, risen like sandstorm on the wind blowing over the hot desert floor. He reached for the crank and tightened the window and tried to turn to the driver, then they were under the veil, the cab awash in a hushed pelting, and his nostrils stung in the bite of burnt oil rushing in from the truck’s leaky engine, and he could smell rancid food and taste the acid of digestion. Again he tried to turn. The windshield was opaque now, and he saw the driver’s hand, the wipers smearing the dead bugs, and felt the truck lugging down. The hand was shaking on the shift, the heavy load behind them pushing the cab forward against the gears and he felt the brakes grab. Was it his father? He couldn’t move his head. The door was open now, wild smell of decaying desert flowers coming in, and he saw the wet rag in the bug smear and a swath of clear glass and trails of water running down from it. Then he could see the flames in the low buildings at horizon and to the right of that fire, and much closer, the shading oak on a hill in a green oasis. There was someone under the tree, lying in shadow in the grass there, another tending him. It’s me, he thought, one of them. And then he was looking where the windshield met the rubber at the cab’s ceiling and was hearing a faint creaking. He was falling back, and only by hooding his eyes and looking along his cheeks could he see the figure standing at his feet, ángel de la guarda all in white. Then it was dark again and his lid was lifted and it was bright, but he could see nothing. He felt the rag on his lips, bug juice and water, but he couldn’t turn his head, and someone was touching him and he felt a breeze on his leg, and when he opened his eyes again it was night and he heard a murmur of voices. He could turn his head then, and when he did he saw the folds in the white fabric screen and the metal rod and the plastic bag, hanging in moonlight at the top. He heard the hushed footsteps coming and tried to wait for them, but before they reached him he was asleep in a real sleep.

“Have you ever had a head injury, Mr. Ebano?”

“It’s Ébano,” he said, and the doctor blinked and shifted in his white medical smock and rocked on the chair’s swivel.

“Yes. Of course,” he said.

Carlos stared at him, the way his fingers formed a basket at his chest, then looked down at his own hands, the right palm resting over the left wrist in his lap. They didn’t seem his own somehow, and he hesitated to move them since he wasn’t sure he could. He felt a breeze come in at the open doorway, and when he lifted his head and looked over there he saw the body on the gurney in the hall and the screen door and the gravel drive beyond it. A sheet covered the face, but it was turned sideways and the feet were exposed, the twisted toes of a dead old man, skeletal and chalk white. The doctor saw him looking and rose and went to the door and closed it. Then he moved back to the chair again, the plastic hissing as he settled in.

“It happens,” he said, his sigh audible and forced, and Carlos watched his face, and soon the doctor seemed uncomfortable and looked away, then back again, but Carlos was still watching him.

“What is this place?”

“Well,” the doctor said.

He removed his glasses and he was fish-eyed. Then he pressed a knuckle into his eye, then lowered the glasses and glanced at the closed door. He was short and pudgy, his skin pallid, and his hair was thinning, though he looked only in his thirties. He seemed unable to continue, stuck for the right words.

“ En Matamoros,” Carlos said.

“What?” He spoke softly, coming back from reverie.

“I got it once in Matamoros.”

“When was that?”

He’d slipped his glasses on and turned. He was focused again, and curious.

“I don’t know for sure. Maybe thirty years ago?”

“Well, I don’t think it is that,” the doctor said. “The cause, I mean. But did you pass out that time? Were you unconscious?”

“No. I don’t think I did then. Just for a few minutes.”

“But you went to the hospital. Maybe there are records still, and we can get them.”

“No. I didn’t do that. I don’t think there was one.”

“No hospital?”

“I was with my father then and we were working.”

“Well I don’t know what to say. I’d like to run a few tests though. Just a few more days.”

“What for exactly?”

“Well, to find out, you know. To get a proper diagnosis.”

“Am I okay now?”

“Yes, yes, I think so. But you were unconscious for a week you know. Can you remember how it happened?”

“Well, you know,” Carlos said, smiling at him and using his phrasing. “Once I was there, and then I wasn’t.”

“Well,” the doctor said. “I don’t know what to say then. We could run those tests. Maybe we could learn something.”

Empresa descabellada , thought Carlos. Then he looked down at his hands again and moved them from his lap.

The attendants were lifting the body into the ambulance when he left the Manor, the sheet tapping at the gurney’s sides in gusts of wind, and Carlos felt the hair flick at his ears and he touched his cap brim to the dead and nodded as he passed by, then headed across the gravel parking lot to Peter’s car. He could see the old house above it in a growing darkness on the hill, and across the meadow to the right was the lighthouse. A few cars were gathered near the base, official seals on the sides of some of them. Thick clouds rolled in from the sea, and he felt a spit of rain on his arm as he climbed in, speaking even before the door was closed.

“Did you ever wear something white?”

He removed his save the lighthouse cap and snugged it over his knee, the bill pointing down his shin, then turned in the seat as Peter got the car going and headed beyond the gravel to the narrow road that would take them to the highway and into Provincetown. The blacktop was cracked and there were places where slabs tilted up and roots pushed through, as if the product of some earthquake, and Peter drove slowly, the car’s wheels in bearberry at the shoulder, avoiding potholes. It was raining and the wipers smeared the windshield, and Peter had to use the washer to clear it.

“You mean when I came to see you?”

“That’s right.”

“No. I don’t have clothing of that kind. A white shirt maybe.”

“Then I guess it was a dream. Or some attendant.”

They reached the highway and had to sit there and wait for a break in the slow winter traffic. The rain rose into mist and the wheels of the passing cars sprayed clouds of wash that drifted over them, and Peter cranked the wipers up to a higher speed. Then there was a space, and he edged out into the flow. Fog had joined the rain now, moving in from the sea, and the traffic slowed and headlights blinked on. He drove near the shoulder, and once they’d reached the edge of Pilgrim Lake he glanced over at Carlos.

Читать дальше