“We were both sad in our good-byes at the bus station, and I think Joaquín had tears in his eyes. I’d saved enough in six months to last me more than a year of good living, and I was dressed in the finely tailored leather clothes and new boots I’d bought in town the day before. I’d bought a new suitcase and a Stetson too, and Joaquín had taken me to his barber for a shave.

“‘You’re looking good,’ he said, as he shook my hand, ‘a little better than when you came. How is your corazón?’

“‘It’ll have to do,’ I said, then squeezed his hand and released it and turned and climbed up into the bus.

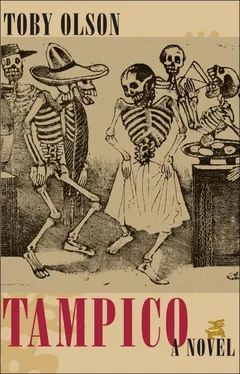

“There were chickens in the bus, a large hog and a couple of painted dogs and a parrot in a cage. And children were laughing and playing games with bones and cards in the aisle, their mothers bent over them in caring scolding and smiling and childish conversation. The bus was crowded, and people were standing and the windows were open, and the driver held a cat in his lap, a tiger cat. I had to bend down from where I stood to see out the window, and I looked for Joaquín as the bus pulled out, but he was gone, and when I rose up again I felt the fingers of the man beside me on my arm and turned to him. He held out a bottle of mezcal and shook it. There was an inch or two of liquid in the bottom and the white worm. I took it and thanked him and swigged from it, then handed it back, a last matter of formality and social grace, leaving Tampico forever.”

It was after one. A curl of smoke rose up from Gino’s pipe and drifted against the windows and dissolved. He was looking out again, and Larry turned from John and watched him. Frank’s chin was on his chest, his hooded eyes on the pencil he rolled between his fingers. He’d been scratching on a yellow pad, lines and figures. A deep, muffled sigh filtered out to them through the screen at the solarium’s side, then Gino turned and took the pipe from his mouth.

“Ah, memory,” said Frank, his pencil active on the pad.

“The lighthouse?” John asked, and Frank nodded, but didn’t look up.

“What about Chepa’s house. What happened there?” It was Larry.

“I suppose it’s gone now. After all this time. I gave the contract to Joaquín, right there at the station as I was leaving. He said it was as good as any deed. I think I said for safekeeping, thinking I’d see him again sometime, but I never went back to Tampico, and I never did.”

“Wouldn’t that be a place to go!” said Gino at the window. Then Frank began.

He and his father knocked up the coop together, soaking corner posts in creosote, then sinking them and framing that and toeing the floor joists in. The floor itself was cut from warped lumber found out in the barn, and they put in a wainscotting and screening and a tin roof at a good enough angle to drain rain. His father went off in the flatbed, then came back with the wire cages and grain, and his mother watched from the porch as feathers flew and the chickens hopped into their new home. His father dug a trench and put in lights and what his mother called the chicken light on a long cord and a place to hang it near the door, and as they stood admiring their work, his mother called out, and they turned and saw the young man trudging up the rutted drive.

It was 1920, and his father had lost everything in horses in Lexington and his mother had lost the proper family she imagined they were becoming. His father had kept enough to buy the collapsing house and the ten acres and the truck that came with it, and he’d taken up the hauling of anything that was available for hauling and that he could lift, and Frank had quit school in his third year and went to work fixing up the house. His father had a wicker rocking chair he’d salvaged and a place for it, under a large old oak on a hill in sight of the house, and Frank would watch from the porch as he sat and rocked there and looked back in the direction of Lexington a good hour away. He’d sip from a bottle and at times would raise his fist to his mouth and press his knuckles between his teeth. They worked together on weekends, and at times Frank would go out in the truck with him, but they had very little to say to one another, almost nothing, and Frank did most of his talking with his mother, listening mostly to her stories of their horsey past and their ascendance in a time he was too young to remember and the things she had planned for this “new” house. She put no time limit on the accomplishment of her vivid images, since there was no money and little hope for it, which was something she avoided mentioning.

The young man was dusty and hatless and the sweaty creases in his brow and cheeks were sharpened by wet dust and he looked older than he was. He needed to wash up, he said, and if there was any work around the place he’d do that, for food, and if there was more to do he could stay on for a while, just for a bed and meals. Frank had moved down from the coop, and the young man looked over at him where he stood below the porch. He said his name was Adam, what’s yours? and Frank’s mother looked up the hill to where his father stood at the coop’s side, and when Frank turned he saw his father nod, and in that nod he saw his disengagement, knowing even then that things were heading toward some ending.

There was plenty to do around the place. The roof leaked, windows hung in rotted frames, the useless barn was a hazard in its tilting and needed dismantling. The house sat below a hill, and rain had flooded down exposing two feet of stone foundation. They needed a runoff trench, and the earth was thick clay after a few inches and a shovel would hardly touch it. Only a pickaxe.

The young man worked hard, and this caused Frank to work even harder. Frank’s mother brought tea out in a jug to darken on the porch, and she watched the young man work, and when Frank moved into her line of vision she seemed to look past him. He knew very little of passion then, almost nothing, but he knew of a kind of absence and had never seen his parents touch each other. His mother, he thought, was in the wrong life, but then his father was too, and he thought that were they to find the right ones they wouldn’t be the same. She took to wearing a kerchief in her hair, a little makeup on her lids, and at dinner he noticed her pared nails when she passed the plates and bowls. The wrong life, he thought. It should be the horsey set, those dresses like soft bells and lawn parties and English saddles, nothing she’d ever had in actuality, though she’d seen it across fences, but a world in yearning, so actual she could almost taste and touch it.

He was heading up to the coop for candling. His father had a two-day-trip job, the moving of farm equipment over in the west side of the state, near Sturgis, and he’d set out with him, but had climbed off at Wilmore. The truck’s cab was close, and there were flies and mosquitoes in it, and a smell of scorched oil came up through the vents and burned in his nostrils, and he got sick to his stomach and had to throw up at the side of the road. And when they reached Wilmore his father told him to go back, it was okay, he could walk around town for a while and get some air. Then he could hitch a ride. There’d be no problem.

And there wasn’t. He caught a ride in a new Buick convertible, a man in a dark suit. They couldn’t talk in the wind, but the air was fresh and his stomach settled, and when the man let him off he was only a mile’s walk from home and was feeling better. When he got up to the porch and looked through the screen there was no one there, and though it was getting on toward dusk and shadows washed over the sink and table, there were no pots on the stove and no lights. He sat in the kitchen for a few minutes, then decided he could do the candling, get it done before dark.

Читать дальше