The trout fills the passenger seat. Its head presses against the armrest of the door. Its tail brushes against Alan Turing’s thigh. Its eye is pointed toward the roof.

“Tell me about your wife,” the trout says.

Alan Turing drives with both hands on the steering wheel, leaning slightly forward. His fingers are stiffening from the work of driving and so he reaches over to turn on the heat.

“What are you doing?” the trout asks.

“I’m turning on the heat.”

“Leave it off.”

Alan Turing does. “My wife is very smart,” he says. He doesn’t look at the fish while he speaks. “She’s intense and I sometimes wonder what she sees in me.” Alan Turing smiles sadly. “Lately, I’ve been distant and, I guess, not very responsive. I don’t know why. Anyway, I became distant and she became distant and the whole thing just kind of snowballed. I’ve been working a lot lately. But that’s not really it. I mean, it hasn’t been work. I’ve been — how can I put it — lost, sick, stupid. I’m simply not happy with life.” Alan Turing glances at the trout. The fish looks bored. “I know it sounds dumb. Midlife shit and all that. But now I’m afraid I’ve pushed Barbara far enough away that she’s looking for someone else.”

The trout seems to struggle with a breath, flops its tail against the fabric of Alan Turing’s trousers.

“We still have sex, but that’s all it is, I think. Sex. It feels so empty. It never felt like I had to search for the feeling before. I’m so scared. We don’t even argue. We’re just creating a gentle, uncrossable distance. And then I get mad and I want to tell her to go away.” Alan Turing is crying. “It’s life, too, you know. It’s this day-to-day stuff. I don’t know why I do anything. I do my research, but it’s for shit. I read the news and it goes in one eye and out the other. I haven’t heard a good joke in years. And my wife is sleeping with someone else and still fucking me.”

The fish says nothing.

Alan Turing pulls into his driveway and turns off his car’s engine. He gives the trout a look and says, “Wait here.” He gets out and walks across the yard, the grass of the lawn he hates so much feeling soft and moist under his feet. His hands are shaking. He enters the house and stands inside the foyer. He calls out for his wife. “Barbara!” There is an urgency in his voice that he hears, that at some other time he might seek to control, but not at this moment. “Barbara!”

Barbara comes down the stairs. She is wearing a robe, a towel wrapped around her head. “What is it?”

“Why do we do this?” Alan Turing asks.

“What’s wrong?”

“Everything’s wrong, Barbara. Look at us. Look at us.”

Barbara clutches her robe closed.

“Yeah, close up. Heaven forbid I should see you naked in the light. It might lead to lovemaking instead of fucking.”

“Alan,” she complains.

Alan Turing is pacing. He stops and stares at her. “What’s happened to us? To everything?” Inside his head, reality seems far away and unreachable. “Come outside with me. I want to show you something.”

“I’m not dressed.”

“It doesn’t matter. Come on. Come on!”

Barbara flinches.

“Come on,” Alan Turing says more gently.

“Alan, you’re scaring me.”

“I’m scared, too.”

“What do you want to show me?” she asks.

“Just come with me. Please?”

Barbara nods and steps through the door he is holding open for her. She follows him across the yard. He leads her to his car in the driveway. He turns and watches her look across the street for neighbors.

At the car, he looks in and the big trout is not there. There is a very little minnow dead on the passenger seat of his car. He feels near to fainting and turns, squares his shoulders to Barbara.

“What is it?” she says.

Alan Turing looks at his wife’s eyes, tries to hold them, tries to memorize them. He looks at her lips and her ears and her nose. He touches her hair.

“What is it, Alan?”

He says, “I love you.”

The Devolution of Nuclear Associability

We are all too familiar with Saussure’s

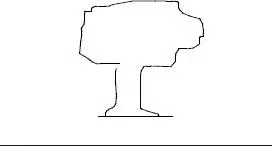

and likewise all too familiar with the notion that the line separating the signifier and signified is somehow sliding or shifting. And finally, we are as familiar with the instructional icon:

Arbor

As elementary as these concepts might now seem, I begin with them as Semiotics begins with them.

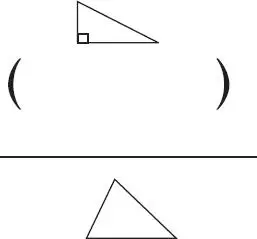

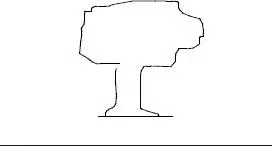

So, I ask you to imagine a character, Adam. Adam is deficient in a singular linguistic way. He is never quite able to say what he means. Adam often gets very close, but never realizes his intention. Adam might attempt to explain the Pythagorean Theorem, but can only manage to get across that the sum of the squares of two sides of a triangle equals the square of the third side, being unable to make clear that the third side is the hypotenuse. Likewise, if Adam means to draw our attention to a right angle, he can only manage triangle. So, that space or gap between the signified and the signifier is never quite crossed. We get:

Since nature abhors a vacuum, something must fill that space. To say that it is nothing merely begs the question. For if Adam, with his peculiar problem, were to intend to mean triangle, he would only be able to convey geometric shape. We have then:

Geometric shape

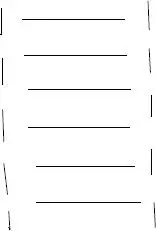

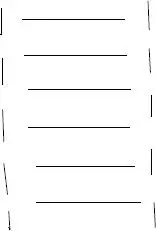

If we place above this Adam’s attempt to offer the Pythagorean Theorem, then we see a ladder of sorts, which we might consider bounded on either side by some associative thread:

We can well imagine how this disability of Adam’s can prove frustrating. Especially when he attempts to, say, summon help to his burning house, he being capable only of directing the firefighters to a house near his or to one that looks much like his, his meaning becoming twisted in his frantic efforts, much as our meaning often twists.

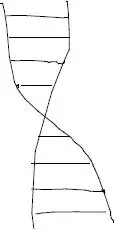

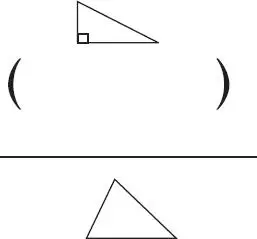

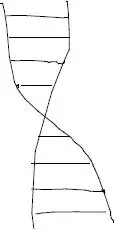

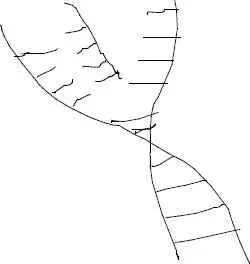

Meaning is difficult enough without metaphor and metonymy. But imagine Adam undertaking to say something subtle and metaphoric. His meaning will not only fall short, but might, in fact must, be misconstrued by misdirection. His ladder of meaning breaks:

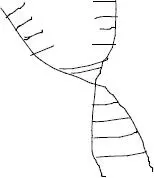

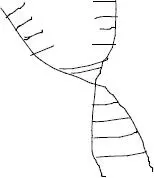

And depending on the situation in which his attempt is made, his broken meaning can accept (un)intentional connotational import, which we’ll call contextual clutter, and so looks like this:

Читать дальше