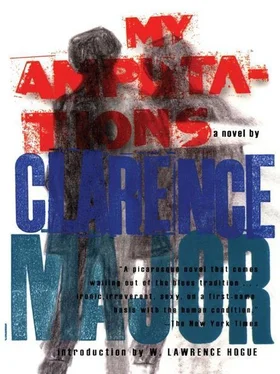

Clarence Major - My Amputations

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Clarence Major - My Amputations» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2008, Издательство: Fiction Collective 2, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:My Amputations

- Автор:

- Издательство:Fiction Collective 2

- Жанр:

- Год:2008

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

My Amputations: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «My Amputations»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

My Amputations — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «My Amputations», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Unable to find his identity in Europe, Mason travels to Africa. Certainly, in Africa, he should be able to find himself, being black and a descendent of African slaves. Making it clear that he has no desire to deny race, Major/the narrator tells us that he is “not the Invisible Man; yet race — or its absence — remains part of [his] identity.” But he is “concerned with an encamped deeper sense of who I am, this character that is me” (64). In Ghana, Mason is greeted with “Welcome home, Brother.” He responds with gratitude, but the narrator asks, “But did Mason feel at home? How black was Blackface Hermes?” (182) Mason also meets a wise Liberian tribesman who gives him an envelope, which is supposed to hold the secret to his identity. When he opens and reads the one-sentenced letter, it says “Keep this nigger” (204). The tribesman tells Mason that he has come to the end of his run. There is no resolution, and the journey to Africa does not tell Mason who he is.

Although Mason does not find wholeness or absolute knowledge in his journey, My Amputations does present, in Mason, a complex and varied African American, who belongs to America, Europe, and Africa. In addition to being black, Mason has other class identities, subjectivities, and dimensions. He is as good and as bad as any other human being. He is an ex-convict, a father who leaves his children, and a writer. Although he experiences racism in the Air Force in Texas and Georgia, he is more than the representation of a set of denigrating experiences. He is also a modern, fragmented subject of diverse and varied experiences who is asking questions and seeking answers about who he is. Lastly, Mason is also a de-centered, fluid, post-modern “black” subject. He knows jazz and blues, but he also knows European classical music and art. His reading and artistic tastes run from Dante, Dickens, Michelangelo, and good Saul Bellow to Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, and Charles Wright. He not only steals C. M.'s identity, but he also shows traces of Ellison's Invisible Man, Wright's Cross Damon, Melville's Confidence Man, and Defoe's Moll Flanders.

Unconcerned with realism, conclusions, and resolutions, My Amputations focuses on process, imaginative spaces that open up the novel to other human possibilities, to a different way of thinking about social reality. For example, Mason's father, with his wings, projects himself into another time, another place, where he is in Kansas City listening to Duke Ellington, taking off with Cab Calloway toward the sunrise. He becomes many things: a jailbird, a music lover, a heel, a grifter, a lady-killer. He hangs out at card parties and Saturday night fish fries. In another example, in Nice, Mason loses himself in a museum, which becomes a “place of unfolding possibility. Moors and cows and plush pink underwater plants and shimmering fabrics and trembling virginal couples floating near the edge of space turned him around, pulled him under their spell. Put him on an insane spin up through mountain roads of canvas, down through sea-level pathways of suicide-fears. A mermaid's scaly skin rubbed against his naked arm. Mason stepped up into the canvas and entered the home of an old rabbi” (178–179). Desiring “kinship” but being ostracized by the community, Mason experiences being an imposter. In a final example, in Africa, Mason is able to “climb onto the back of a butterfly and fly to larva heaven. Or turn himself into a desert spiny swift and dart across the rock of the universe! or get involved with a revolutionary group and become an international hero” (180). Combining the real and the fantastic, My Amputations unleashes fresh energy and imaginings, allowing the reader to think and to imagine certain possibilities. This new way of thinking about social reality entails a life-affirming play, where the acceptance of chance, contradiction, ambiguity, indeterminacy, open-endedness, and heterogeneity is a part of the world.

In the world of My Amputations , traditional assumptions are burst asunder, transforming and rewriting reality and history. Reality is extended into infinite possibilities. Thus, in My Amputations , Major uses and abuses language to renew it, to reform it. In exposing narrative realism, Major reproduces a non-referential, indeterminate, fluid, and open postmodern fiction. He also reframes and re-describes the African American outside existing racial stereotypes.

Today, we think of postmodernisms as known quantities, with distinct features and characteristics. They permeate music, movies, television, architecture, dance, sociology, and literature. Clarence Major's My Amputations is no longer an aberrant, experimental novel. Rather, it is now reconfigured as a forerunner in the intervention of postmodernisms into American culture and art. It is a masterful artistic object that speaks our postmodern parlance, reinforces our postmodern vision, and assumes our sense of postmodern social reality. It continues to endure, inspiring new imaginings with each reading.

Notes

1. John O'Brien, “Clarence Major.” Conversations with Clarence Major , edited by Nancy Bunge (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2002), p. 10.

2. Doug Bolling and Clarence Major, “Reality, Fiction, and Criticism: An Interview/Essay.” Conversations with Clarence Major , edited by Nancy Bunge (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2002), p. 29.

3. Alan Katz, “Transition Is Tugging at a Local Avant-Garde Author.” Conversations with Clarence Major , edited by Nancy Bunge (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2002), p. 53.

4. Clarence Major, ed., Calling the Wind: Twentieth-Century African American Short Stories (New York: HarperCollins, 1993) p. xvi.

5. Nancy Bunge, “What You Know Gets Expanded,” Conversations with Clarence Major , edited by Nancy Bunge (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2002), p. 112.

6. Larry McCaffery and Jerzy Kutnik, “Beneath a Precipice: An Interview with Clarence Major,” Conversations with Clarence Major , edited by Nancy Bunge (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2002), p. 73.

7. Jacques Lacan, The Seminar of Jacques: Book I: Freud's Papers on Technique 1953–54 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 66.

My Amputations

Again, as in a recurring dream, Mason opened the closet door and stepped hesitantly into its huge darkness, its nonlineal shape: he pulled the door shut then crouched there on the floor — which seemed to be moving — with the breathing of The Impostor. This dimness was not illuminated by the glowing Mason felt. He could smell the man: his sweat, his urine, his oil. The skin of Mason's eyes was alive with floaters. Faintly in the background — perhaps coming through the wall from the next apartment — Sleepy John Estes was singing “Married Woman Blues.” Mason pushed hard for the beginning, some echo or view. Anglosaxon monosyllables clustered there. He couldn't remember how it all started nor even his muse's birth. He called her Celt CuRoi. Yet memory was expanding… Low clouds crawled against a terrible sky. Lots of rainstorm-damaged trees, houses, fences. His birth—?—came like that. He swore to the date, the year, the damage, the blood. And afterbirth… and his broken-grasping for sea, land, form. Why'd he remember overturned cars, the Great Flood, a woman up in a tree, words: nigger, jig, darky, convicts at gunpoint working to rebuild a broken dam, a six-hundred-or-more death toll…? and, and from eighteen Woodrow Place? river moving out to lake, to sea, to ocean. Sea?… already searching for it: to float upside down in its membranous-liquid grasp. Giant sharks might be deep in it but Celt would guard… yet she, too, was only a beginning — not a sailorette, joe, just ah… bug-examiner like Lil Massy: transparent wings, pink underbelly bright and silky as panties — mating dogs smelled like a rain forest full of moss and rotten logs. First letter of alphabet fascinated them: a house: Egyptian pyramid, farmer's joke; picture on box of crayons; then D: door to darkness, closed-off mystery. Together they went down the earth-passage — at underworld's first level Celt and Mason dimly expected to encounter themselves waiting — locked in a dark, secret, everlasting closet. Instead, they stood uneasily on the bones of a dog-like animal dead a million years. On level two they plowed through the remains of a dinosaur already taped and labelled MRF. They uncovered the majority — but were too innocent to connect… to force . Strutters, diwalkers. V was clearly an upside-down hat: it protected them the way back up where — just before the exit — they stumbled into the clutches of cruel aunts with syphilitic-eyes, long-eared witches, drunk crab-shaped uncles, the broken — yet joyous, powerful, love-bound — spirit of a people: his — and by spirit, hers, too. They tasted salt, sugar and felt the frozen ground in winter; watched bird feet, were stung by fish fins. Turkey rot! Mason and Celt discovered it was possible to fly — even with broken wings: flying was not why you are but how: and then why: it was also not rushing downstream on a raft or being engulfed by a storm or swept away in a flood. It was how he got to know Celt. Before Celt he'd been a blind bat struggling to embrace the sky: his spirit existed before he was born: he simply stepped into it — as though it were a Union Suit. At sixteen he was unfinished; eyes: large, blank brown things. Did his mother Melba love him? She was certainly not his muse. Look at her apron: too clean: something is wrong. Is it that she doesn't like him much but loves…? Her eyes: unfriendly — yet she's a person of responsibility as big as the Atlantic. Small, tight mouth — Anglosaxon. Her skin was lighter than his. He was — in color — between her and his father Chiro: nutmeg. Her Irish-African eyes? His were more in the tradition of Chiro's. As Mason grew: there was laughter in his thunder while he beat his wings against the page — attempting to become a good writer. He jus' grew: Chicago, 1955: there's Mason along the lakeshore: gulls cry. In the stockyards: pools of blood from the slit throats of hogs. He heard Wind Voice here howling in from lake Michigan. He claims he swallowed the lake. Art Institute's lions roared at traffic. Ashtrays and pink salmon. Calendars without dates. A private collage: he was reborn constantly in it: to the gills he settled in this stuff. Distractions, spectacles —where'd he find the force for his connections, a vent for the smoke clouding the thrust of his crisis? And how to fit in simple things, moments, only he knew the shape of — or so he claimed. Hold his hand, reader. Example: a particular line in the sky, skywriting — a particular rose on a particular bush — bushwriting. No echo; no snow in the hills — which hills? Wyoming, of course. He tried too hard to be, uh, profound. But he was young: eighteen. Take him by the throat, dear—. He thought himself, he says, Rimbaud or somebody. The sky, roses, appletrees, you name it. He says William Carlos Williams wrote him, encouraged him. He came to realize he wanted it all flat or upright and permanent like cubism — like things: surfaces. Now, here in the closet there was a feeling not of claustrophobia but one of plague, glut, glue; a sense of pestilence — and redemption — worse than East Africa—1368, a glut worse than Henry the Eighth, a glue thicker than Egyptian cement. Mason: holyshit: heard the pained-breathing louder than ever, smelled The Other with pity and contempt. He was no longer squarely sure these sounds, these smells, were not his own.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «My Amputations»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «My Amputations» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «My Amputations» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.