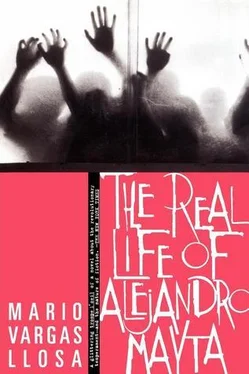

Mario Llosa - The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Mario Llosa - The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1998, Издательство: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta

- Автор:

- Издательство:Farrar, Straus and Giroux

- Жанр:

- Год:1998

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

During the first days, the newspapers were filled with these events and devoted front pages, headlines, editorials, and articles to what, because of Mayta’s past record, they deemed an attempted communist insurrection. An unrecognizable photo of him behind bars in some jail or other appeared in La Prensa . But, after a week, people stopped talking about it. Later, when there were outbreaks of guerrilla fighting in the mountains and the jungle in 1963, 1964, 1965, and 1966—all inspired by the Cuban Revolution — no newspaper remembered that the forerunner of those attempts to raise up the people in armed struggle to establish socialism in Peru had been that minor episode, rendered ghostlike by the years, which had taken place in Jauja province. Today no one remembers who took part in it.

As I fall asleep, I hear a rhythmic noise. No, it isn’t the night birds. It’s the wind, which slaps the waters of Lake Paca against the terrace of the inn. That soft music and the beautiful, starry night sky of Jauja suggest a peaceful land and happy, tranquil people. They lie, because all fictions are lies.

Ten

I visited Lurigancho for the first time five years ago. The prisoners housed in building number 2 invited me to the opening of a library, which someone decided ought to be named after me. So I accepted their invitation, in part because I was curious to find out if what people said was really true about the Lima prison.

To get there by car, you have to drive by the Plaza de Toros, cross the Zárate neighborhood, then go through some slums. The slums eventually turn into garbage dumps, where you can see the hogs from the so-called clandestine pig farms feeding. Then the asphalt runs out, replaced by potholes. Soon the cement buildings emerge in the humid morning light, partially blurred by the mist. They are as colorless as the sand flats around them. Even from a distance, you can see that the innumerable windows have no glass in them — if, in fact, they ever had glass — and that the movement in the tiny symmetrical squares are faces and eyes peering out.

What I remember vividly from that first visit is the overcrowding, those six thousand prisoners suffocating in an area meant for fifteen hundred, the indescribable filth, the atmosphere of pent-up violence on the point of exploding. Mayta was in that anonymous mass, more a horde or a pack than a human collectivity — I’m absolutely certain of it. It may be that I saw him and that we waved to each other. Could he have been in building number 2? Would he have bothered to attend the opening of the library?

The buildings stand in two rows, the odd-numbered ones in front, the even-numbered ones in back. The symmetry is broken up by the cell block for fags, which is up against the wire fence along the western wall. The even-numbered buildings are for recidivists or felons, and the odd-numbered ones house first offenders who haven’t been sentenced yet or are serving light terms. Which means that Mayta has been an inmate of an even-numbered building for years. The prisoners are housed according to their Lima neighborhoods: Agustino, Villa El Salvador, La Victoria, El Porvenir. Where would they have put Mayta?

My car moves forward slowly, and I realize that unconsciously I’ve taken my foot off the accelerator, I’m trying to postpone my second visit to Lurigancho as long as possible. Am I frightened by the thought of finally facing the character I’ve been investigating, about whom I’ve been questioning people, whom I’ve been imagining and writing about for a year? Or is my repugnance for this place stronger than my curiosity about Mayta? At the end of my first visit; I thought: It isn’t true that the convicts live like animals: animals have more room to move around. Kennels, chickenhouses, and stables are more hygienic than Lurigancho.

Between the buildings runs what is sarcastically called Jirón de la Unión, a narrow, crowded alley, dark by day and totally black at night. It’s there that the bloodiest fights between gangs and between individual killers take place, and where the pimps peddle their living goods. I remember clearly walking through this nightmare, rubbing elbows with that pitiful, almost sleepwalking fauna: half-naked blacks, half-breeds covered with tattoos, mulattoes with intricate hairdos — veritable jungles cascading down to their waists — and stupefied, bearded whites, foreigners with blue eyes and with scars, squalid Chinese, Indians huddled against the wall, and madmen talking to themselves. I know that for years Mayta has been running a kiosk where he sells things to eat and drink in Jirón de la Unión. But no matter how hard I try to remember, I just can’t seem to evoke the image of a food stand in the sultry alleyway. Was I so upset that I didn’t realize what it was? Or was the “kiosk” nothing more than a blanket on the ground where Mayta, hunkered down, offered juice, fruit, cigarettes, sodas?

To reach building 2, I had to circle the uneven cell blocks and cross two wire fences. The warden, leaving me at the first fence, told me I was on my own now; not even the National Guard enters that sector, or anyone else carrying firearms. As soon as I passed through the fence, I was surrounded by a multitude waving their arms, all speaking at the same time. The delegation that had invited me formed a circle around me then, and that’s how we made our way: me in the center of a ring of men, and outside the ring, a mass of criminals. The convicts must have mistaken me for some official or other, because they began to spout out their case histories, rave, protest abuses, shout, and demand services. Some were coherent, but the majority were chaotic. They all seemed on edge, violent, not quite in focus mentally. As we walked, I discovered the source of the solid stench and the clouds of flies: a wall about a yard high, where all the garbage from the jail must have been accumulating for months, even years. A naked inmate was sleeping soundly, stretched out on the trash. He was one of the insane, normally assigned to the less dangerous buildings, the odd-numbered ones. I remember having said to myself after that first visit that the really strange thing was not that there were madmen in Lurigancho but that there were so few. It was incredible that all six thousand inmates hadn’t gone crazy in that abject ignominy. And what if, after all these years, Mayta had gone mad?

He was sent back to prison twice after having served four years for the Jauja affair, the first time seven months after being amnestied. It’s extremely difficult to reconstruct his story — his police and prison history — after that, because, unlike the Jauja business, there are almost no written documents relating to the actions he was accused of participating in and no witnesses willing to talk about them. The newspaper accounts I’ve been able to find in the periodical section of the National Library are so sketchy that it’s practically impossible to figure out his role in the robberies in which he was supposed to have participated. It’s also impossible to determine whether they were political actions or just ordinary crimes. Knowing Mayta, you’d think they were probably political, but, after all, what does it mean to say “knowing Mayta”? The Mayta I’ve been researching was in his forties. The Mayta of today is over sixty. Is he the same man?

In which cell block in Lurigancho could he have been spending these last ten years? Four, six, eight? They must all be more or less like the one I saw: low-ceilinged places with faint light (when there isn’t a blackout), cold and humid, with large windows covered with rusty bars, and a hole in the floor for sanitary purposes. To find a place to sleep amid all that excrement, vermin, and filth is a daily war. During the ceremony for the library — a painted box and a few secondhand books — I saw several drunks staggering around. When they passed around little cans so we could drink a toast, I found out that they get drunk on a chicha they make from fermented yuca . Unbelievably strong stuff, made right in the prison. Would my supposed fellow student also get drunk on that chicha when he’s feeling too high or too low?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.