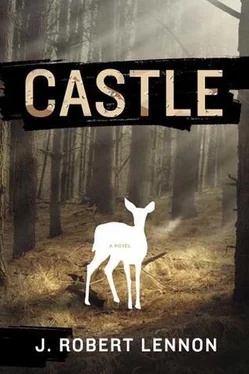

It was the white deer. It had turned, leaping, at the sound of my voice, and now stopped and looked back. It was perhaps twenty yards off, gazing at me over its shoulder. Slowly I stood, not once taking my eyes from the animal. I brushed myself off, watching it watch me. One minute passed, and another. And then it bounded off to the southwest, stepping through the rotting branches. It turned once more before it disappeared, and I understood that this was a sign — that the deer was showing me a path to the rock.

Gingerly, I stepped out of the woods. I paced back and forth along the treeline, and after a few minutes found a suitably large stone, which I hauled up onto the road surface and placed on the shoulder, as a marker. Doubtless it would still be here tomorrow, but I stared hard at the trees, forcing myself to remember their arrangement, just in case.

I had my entry point. And indeed, the deadfall here did seem somewhat thinner than elsewhere, and the ground less saturated. I closed my eyes, recalling what I had just witnessed, the white deer hopping, with weightless ease, from one island of ground to the next, and vanishing into the shadows. Tomorrow, I told myself, I would do the same. I would walk down Nemesis Road, find my marker, and follow the deer.

At 7:00 a.m., after a breakfast of bananas, grapefruit, and oatmeal, I stepped out my door and into the pink light of morning. The sun was low and blinding on the far horizon, the sky streaked with high cirrus, and the air, though cold, was heavy with birdsong and the promise of warmth. I descended the porch steps and crunched across the lot, burdened with gear: my backpack bulged with food and water, a rolled-up tent, climbing supplies, and my compass and binoculars. On my feet were a pair of waterproof boots; lashed to my pack were the climbing shoes and helmet the sneering sporting goods clerk had grudgingly sold me. I had slept well, better than I had at any time since my arrival on the hill. I’d risen at dawn and watched the sun rise behind the rock as, tacked beside my window, the child’s castle drawing served as an inspiring symbol of the endless possibility of adventure.

I marched north on Phoebus Road, retracing, in reverse, my route back from yesterday’s reconnaissance. The pavement, cracked and uneven, was still damp from the rain. I tested my boots by splashing through puddles — though my canvas trousers, tucked in and laced fast, were soon dotted with wet, my feet remained warm and dry. I was alert to the possibility of oncoming traffic, the disturbing encounter with the rusted pickup being fresh in my mind, but my overall mood was one of excitement and confidence. Any passerby, watching my progress along the treeline, would have seen a man who appeared younger than his years, a spring in his step and a sense of purpose in his stride. I leaned forward and, pacing my breaths like a swimmer, plunged forward, as if on a mission of great importance and priceless reward.

After my turn onto Nemesis, it took less than ten minutes to reach the entry point I had discovered the day before. The marker stone was still in its place, the pattern of tree trunks precisely as I recalled. I lifted the stone and tossed it into the weeds at the roadside. Then I took one last look at the brightening sky and plunged into the woods.

In spite of the brilliance of the day, and of the trees’ nascent foliage, I was instantly enveloped in gloom. The temperature dropped fifteen degrees, the light winked out, and a sense of unease began to insinuate itself in my mind. After four or five careful steps into the forest, I peered over my shoulder at the world I had just left. I could make it out, of course — the shoulder, the pavement, and the woods on the other side — but already it seemed impossibly distant. Indeed, it was as though I had been cast back in time to the middle of January.

I suppressed a shiver. My sense of dread was nothing but foolishness. It wasn’t so dark here that my eyes couldn’t adjust; nor was it so cold that my bushwhacking efforts would fail to warm me. Nevertheless, I found myself in the grip of a creeping despair, a premonition of exhaustion and failure.

This was not the state of mind I was accustomed to, at the outset of an expedition. But one does not fight the battles he wishes to fight; he fights the battles that find him. I would do my best to ignore my foul mood and physical discomfort, and plunge ahead as I had planned.

The white deer, I recalled, had fled southwest, and so it was in this general direction that I began to move. As before, the going was slow. Branches that appeared sturdy snapped underfoot, plunging my legs deep into mire; clumps of humus that seemed insubstantial harbored heavy stones, sending me sprawling onto the saturated ground. Low-hanging boughs scraped my face, or released a torrent of water as I ducked beneath them, chilling my scalp and neck.

But I would not be, and was not, deterred. I struggled forward, for hours it seemed, and I did not look back until I felt that I had made sufficient progress. Indeed, when at last I did turn around, there was no sign of the road I had left, and no noise from passing traffic.

In fact, there was almost no noise at all. The forest had insulated me from the raucous birdsong I heard when I left the house, and whatever creatures the wood concealed were silent.

By now the sun was likely overhead, but the light that came down through the branches was gray and weak. The trees were tall here, extraordinarily so, and it was difficult to imagine this land ever having been farmed, as the title abstract had suggested. I took a break underneath a towering fir, to catch my breath, get my bearings, and confirm my route to the rock.

But my mind, in defiance of my aims, grew cloudy and began to wander. I suppose that, given my exertions since I left the road, and my singleness of purpose up to this point, unfocused thoughts were to be expected, and even perhaps welcomed. But I was not used to them and did not wish to indulge them. I have learned that there is nothing more dangerous than a mind that strays from the task at hand. Of course, here there was no immediate danger, and I could not have been said to be working; but old habits die hard, and this was one I had hoped to preserve.

It was unclear to me whether these muddled thoughts were the result of my uncharacteristic musings upon the past which I had indulged the previous day, or if they indicated a general ailment of which yesterday’s thoughts were also a part. In any event, that indulgence was proving to have been a mistake. I tend to align myself against the present cultural obsession with the past — I am not interested in the ethnic and geographical origins of my family, nor in the circumstances of my parents’ meeting, nor that of their parents, whom anyway I can barely recall. I do not like to reminisce about my own childhood, or remember pleasant moments in my life. I don’t keep journals or photo albums, and in general am not prone to reflection at all. I make my most important decisions according to the facts on the ground, and do not allow the past, or some sentimental interpretation of it, to interfere with my present actions. Furthermore, once I have made a decision, I abandon all resistance to it and act upon it immediately. This process rarely fails to deliver the results I need, and when it doesn’t, the consequences are never worse than those that would have befallen me if I had failed to act at all.

However, it would be wrong to imply that my visit to my parents’ graves was of no significance. The same instinct that I had long relied upon to accomplish my work had driven me to the cemetery, in defiance of what I thought I was supposed to be doing, and I had to trust that there was some practical purpose, at this juncture in my life, to revisiting the past. Perhaps it was this apparent contradiction in my personal philosophy that was muddling my mind and causing me to feel tired, exhausted even, to a degree far in excess of that which the day’s physical efforts would seem to have justified.

Читать дальше