“My dad would come into my room, sit on my bed, and sing me folk songs,” she recalled. “He sang ‘Leaving on a Jet Plane’ and ‘Kisses Sweeter Than Wine’ and ‘Long Black Veil.’ But my favorite was ‘Brown Eyes.’ At least that is what Dad told me it was called. It wasn’t until years later that I found out the song was called ‘I Still Miss Someone.’ And it was about a sweetheart with blue eyes, not brown. I have brown eyes so he changed the song for me.”

Turning to me with a shy smile, Emma sang:

Though I never got over those brown eyes

I see them everywhere

My dad he would rewrite folk songs

And kiss away all my tears

Emma’s voice was pure, sweet, and strong, reminding me of my long-ago lost boyhood voice. She took the song I first heard from Joan Baez and reinvented it. The years fell away. I saw myself sitting on the edge of my little girl’s bed, holding her hand, offering comfort in the best way I knew how — through song. Now a beautiful young woman, my daughter was singing to me, helping me on a journey to a new phase of life. I savored the magic of the moment, realizing that what I had given her had come back to me in ways well beyond my imagining.

Then it was my turn. Looking around the room, I realized that my web of relationships was built on familial bonds, friendship, music, work, and my religious life. People knew me as a teacher, colleague, friend, and fellow congregant. Almost no one there, though, knew me as a musician. The time had come to discover if I really was one. I was not nervous. I believed in my open strings.

“Over the last sixty years,” I began, “I’ve used words, millions of words, in books, articles, lectures, and countless conversations. But some things cannot be expressed in words alone. Words cannot express my thanks to all of you for coming tonight. Words cannot express my love for Shira, who has stood by me — and put up with me and my music — for all these years. Neither can words express what a blessing my children are. The mere thought of them fills me with joy, amazement, and pride. As my beloved cello teacher Mr. J used to say, ‘When words leave off, music begins.’ So tonight I want to express myself in music.

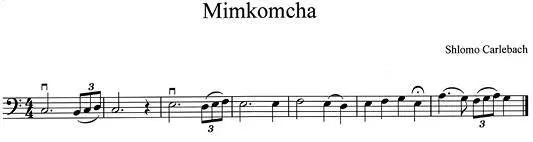

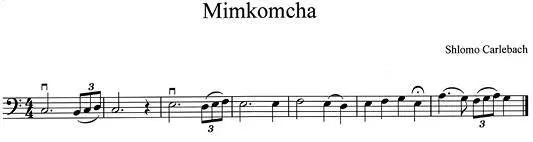

“Forty-seven years ago, at my bar mitzvah, I could sing ‘Mimkomcha’ by the great Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach. Like Emma, I hit all the high notes back then. I can no longer sing it — my voice isn’t what is used to be — but I can play it on the cello. I can, so I will. I also want to play Minuet no. 3 by J. S. Bach, but I cannot play it alone. So I have asked my son Judah to help me on cello and our friend Jay to join us on keyboard.

“And now, ladies and gentlemen, my birthday program, ‘From Bach to Carlebach.’ ”

Judah and I took our seats and tuned our cellos. I took a few extra moments to run through my open strings. Then we nodded to Jay at the keyboard and the Bach began. Minuet no. 3 is one of the most famous Bach pieces, and while I can’t easily create it here on the page, it’s a dance that you’ve heard a hundred times on the radio or in an old movie. It’s the quintessential minuet and goes like this:

More than a song, our performance was a musical conversation, first among Judah, Jay, and me, and then among all these friends in the room. I noticed more than a few people quietly humming along.

I played expertly through the “major” opening section but then I lost my way — as I feared I would — during the “minor” section. But Mr. J was prescient in suggesting that I enlist Judah’s help. While I sat out the minor part, Judah and Jay soldiered on without me. Luckily, the piece ends on a repetition of the major so I don’t think anyone noticed my momentary lapses. Not from the sound of the applause, anyway.

With the Bach properly dispatched, Judah and Jay left the stage and I was alone with my cello. I took a deep breath and played “Mimkomcha,” without sheet music and entirely from memory, with all of its over-the-top beauty, longing, and emotion. Again, Mr. J was right. This one I could do alone, without him and without Judah. Here’s a taste of “Mimkomcha”:

As I pulled the bow across the strings, I could feel the “soul” of the cello emerge and connect with my soul. For a moment I was taken back to my bar mitzvah, singing with all my heart. My mother was there; my father was there; together, if only for a moment. Mr. J was there. Rabbi Carlebach was there, too, and I even think I saw Bach hovering about after listening to us playing his minuet. I found my rhythm. I found acceptance in the faces watching me. I found a sense of wholeness and joy in the moment as family, friends, music, and memory merged. It took sixty years to get there, even longer than the forty years the Israelites wandered through the desert. But the journey was worth it. I had reached my musical promised land.

After the party, I felt that if I never played another note on the cello again, I would die a happy man. I was a musician. Maybe that wouldn’t be the first thing that the newspapers would write in my obituary (if there are still newspapers), but playing music is definitely and indisputably part of who I am.

I had reached my goal, but I couldn’t stop playing, of course. Since my birthday concert, many unexpected and wonderful opportunities have come my way. In my sixty-first year, as part of a citywide summer celebration, Make Music New York, I joined LSO for a concert in Central Park. Make Music New York takes place every year on June 21—the longest day of the year — and offers one thousand free musical events in public spaces throughout the city in what New York Magazine once called “exuberant overkill.” There are similar music-making events on June 21 in cities around the world.

LSO’s assigned spot was a sun-dappled pedestrian promenade overlooking Central Park’s storied Wollman Rink, the ice skating site best known as the setting for parts of the 1970 Hollywood tearjerker Love Story . It was a clear and crisp day. As it was the beginning of summer, there were no ice skaters going in circles to the sounds of Frank Sinatra’s rendition of “New York, New York.” Instead, the rink had been transformed into a very non — New York City scene: a carnival that you’d expect to see at a county fair. There was a Ferris wheel, a merry-go-round, and twirling rides designed to induce thrills and nausea. Country-and-western music blared from every speaker.

The LSO members arrived one by one on the promenade and were stricken. “How are we going to compete with that?” we wondered out loud. “Why did they put us here, next to a carnival?”

Our conductor, Magda, was undaunted. She said that we would just have to outplay the honky-tonk. And we did. We played louder and with more confidence than we do at our rented space or at our usual “open rehearsal” concert space at Ramath Orah. Magda had prepared us for outdoor playing. She had warned there would be many distractions and told us that we were to ignore them all. “There are no subtleties out here,” she said. “The aim is to play louder than all the distractions. And, remember: never stop playing.”

Though we had only about twenty minutes of material in our repertoire, the event organizers had booked us for an hour-long performance. While I was initially worried about boring the curious folk who had begun to assemble, our limited playlist was not a liability since our audience was a peripatetic one. Ambling past were families on their way to the amusement park below us, softball players in their team jerseys on their way to a game, couples strolling hand in hand, dog walkers with their designer pooches, Frisbee throwers, ice cream lickers, and tourists galore. Some passersby stopped to listen for a minute or two. Others took seats on the nearby park benches or found a place on the grass. Shira, in for the long haul, spread out a blanket, opened a bottle of wine, and was soon joined by our friends Scott and Ellen, who came to hear me play (and keep her company).

Читать дальше