Unconsciously, I had started to back away from the blank cartouche, as though I suspected in it some power to ensnare me still, to wind me deeper in extremities of self-love and self-deceit. I backed away. My feet scraped sound from the floor, cutting through the silence that had swathed my thoughts numb, letting in flashes of fact: the certainty that the door behind me had locked; the conviction that I would find in it no mechanism of release; the faint but definite indications that my flashlight was failing; all the long distance at my back, of corridor and chamber, unscalable wall and empty sky; and beyond that sky, over the ocean my life in ruins behind me; and before me a darkness pulsing, deeper, blacker, until the real darkness closing in seemed only the ashen shadow of despair. My heart stood on my shoulder, shouting. Against the darkness I saw, repeated in flashes that came to me with the vivid immediacy of lightning, the leathery stare of horror in the face of Nur-Mar’s Answerer; I remembered how we had found him crouched, head furled close to his drawn-up knees: I felt the same urge tightening in my chest, struggling to curl itself around the void left by my soul.

I do not know — and even now some fugitive spirit of curiosity will not let the question alone — just what it was that made me stop. Perhaps it was the panic seizing me at last. Perhaps it was despair. But I suspect, rather, it was the perverse spirit that has led me so infallibly to this place. It had not finished with me yet. I was to be its toy some hours more. Whatever it was, it prevented me from taking the final step backward, which would (I think of it now with regret) have been my last. It would have been much easier to tumble in blindly backward, not knowing until too late just what my feet had done.

Air breathed up the back of my neck. The hairs there stirred. A smell — not damp, not dry but infinitely corrupt — penetrated finally through my terror. Some sense for which I have no name registered emptiness behind me. As if in a dream, or acting out in waking life a dream I had long ago forgotten, I turned, knowing already just what I would find: a pit some ten feet across and immeasurably deep occupied the center of the room. In the same uncanny doubleness I teetered, caught in the centripetal pull of the pit but unable, finally, to allow myself to fall.

I fell back instead to lie in darkness. Ghostly chuckling echoed upward from the mortar my foot had dislodged, loosening more echoes from the depths of the well. I heard no impact.

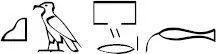

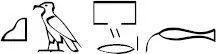

I lay for a long time before lighting the torch again. The ceiling was low, and marked, above the center of the well, with a small gathering of glyphs: Akha , it read: enter, go. But when I looked more closely, I saw that the word was incomplete: the last sign of the glyph was broken. Either the engraving was shaved plane, or the stone had fallen into the well, but I knew, as plainly as if it had been spoken aloud, as if I had always expected to find it here, what the entire glyph would be. Akha-t , the glyph had said, still echoing over the empty centuries the pride and despair of a King, and a cynicism deeper still. The glyph gestured to the well at my feet, embracing as well the immense edifice around me, the King’s death, my own life, and all the world of light that I had lost long, long ago: Akha-t : a disease of the womb.

I had found what Khafre’s Sphinx was still seeking in the sky over Giza: the answer opened at my feet.

There was little else to do. I knew better than to try the door, although I did. I knew better than to search the walls and ceiling, to pry at the joints between the stones, but I did. I did these things, and several others, until my own bloody fingerprints marked the room. Time passed. The air in the room grew foul, and not all of the foulness came from the well. The flashlight, no matter now I saved it, grew dim. I was hungry light-headed, and the voice in my ears was loud.

Only one discovery did I make in these hours in my tomb, one last contribution I have to make to human knowledge. Forgive me: the dreadful cynicism of the King’s last gesture is infecting me at last — or my own despair has finally unleashed itself, now that there is no shred of human society left to hold it back. But if I am bitter, it is not without reason. He did not leave me even so much of my pride as this: even this, my last discovery, was determined long ago, this neat stack of papyrus placed here at the margins of the floor where, sooner or later, I must stumble over it.

And obey.

As though they held some potent spell, once I found the sheets of paper I had no choice: Ser, Serr, Ser metut: arrange words in order, compose a work: write. Of course the papyrus crumbled through my fingers: dust, swirling in the last rays of my flashlight. I thought at first that this too was another piece in the puzzle, another refinement of a torture I could hardly understand: to be commanded to write, and given only dust. Almost I rebelled again: I shoveled the ashes down the chute. But when I found the pens, purest ivory, still supple and sharp, bound with a linen cord beside their alabaster ink-pot, the powdered ink waiting in its stoppered flask, I gave myself up at last to the command. I sat, I crossed my legs in the old, familiar posture of the scribe, and ari metchut: I made a book.

The fluid for the ink I supplied in the only way I could. My pockets I emptied for what small evidences of my past they could provide: my journal notebook, scraps of letters, old index cards. Words came to me out of the darkness. And although I cannot see what I write, these words will suffice. They will survive me, I know, just as the King’s monument survived him: as long as time requires, and the darkness in the pit endures.

Out of that darkness, reader, I reach my hand to you.

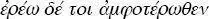

— ODYSSEY XII: 58

It was a fair cruise, the seas calm, the winds and currents favoring, the skies so clear the evening star was visible by day. Mornings and evenings low clouds rolled, pink in the sunrise, orange in the west; always they vanished before us. The crew, off watch, hung in the shrouds, where they swung with the long surge of the sea; high in the foretop, Teofilo, the Portygee, sang in his languid tongue. This was in the days before the Law.

On the fortieth day we spoke a ship, heavy-laden out of the east. Its captain told us that the Law had come.

“What is the Law?” I called back, but the ship had drifted out of hailing. It settled over the horizon, and we never saw it again. On the sixtieth day, we spoke a black, lean ship, an eye painted on its prow. Its captain howled at us like a madman, and evidently he was mad, for his crew had tied him to the mast, and rowed as though the devil was after them. We pulled away on a freshening wind.

On the ninetieth day, in calm seas we spoke a monstrous vessel, all iron and smoke among the ice. It told us, too, the Law had come, but when we asked what this Law might be it only forged ahead, full speed into the night. And on the last day of our voyage, as the lighthouse top rose out of the west, and then the steeple on the hill, and we made our way into the harbor, clear and smooth as glass, the shadow of the moon ghosted across our wake, a shudder shook our canvas as if the wind had died, and a hollow voice from astern told us that the Law had come.

Читать дальше