At Cairo airport, I had nothing to declare.

The long duration of an afternoon that should have been night I kept to my room, the curtains drawn against the glare. My window faced west, and as the afternoon wore thin and finally unraveled, the curtains caught cold fire; the window was a blaze of gauzy orange, reddening. In the midst of the glow, a black circle pulsing. Outside, in the heat and light, cars gathered, bleating. I lay and watched the pulsating void, listened to the thread of beeps and baas, and in the distance, on a wire stretched somewhere in the recesses of my skull, a thin voice was chanting.

The room was red and dim around me, and the voice had somehow escaped into the evening, where it ululated across the domed and minareted roof of Cairo: evening prayer. I stumbled from the bed and threw the curtains open. Beyond the new city the Nile shimmered around Rawdah. Beyond lay Al Jizah, where I told myself I could see the buildings of the University, where Professor — and I had stayed the first evening of my first trip into Egypt. And beyond Al Jizah, black against the blue-green-gold of the horizon, the Pyramids.

I could not see the Sphinx, but I knew where it lay, could conjure up the blind face of Khafre staring back at me. Blind, and crumbling, and slumping back into the sand.

I drew the curtain across the glass: for a moment my face, pale, gleamed back at me, one arm reaching out from the darkness.

The riddle of the Sphinx — the real riddle, the real Sphinx — is that we do not know the question.

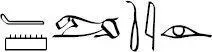

I rented a Rover through the auspices of the Egyptian Auto Club, located conveniently around the corner from the Museum where the relics of Nur-Mar rest. I did not pay the visit. In my two days remaining in Cairo, I made three stops. One to the Etymological Society, up the broad contorted snake of Ramesses Street. I brought with me some copies I had sketched of some of the later marks from Nur-Mar’s papyrus which still perplexed me. I hoped they would perplex them as well.

My credentials were enough to grant me entry to the Director, a fellow who, behind two solar discs of eyeglasses, looked a bit like Gandhi. He peered with his magnifiers at my sketches, and then looked up at me with the same abstracted stare.

— Where did you get these?

I told him something like the truth. He remembered the excavation, of course; the glyphs had been printed on the seals of certain jars, I said. It is easy to lie, to lie gracefully I find, when the face of your listener is hidden in a pool of black. I heard a slow exhalation, a dusty sigh, and when I looked sidelong he had removed his glasses to rub his eyes.

— We see so many of these, he said.

My heart almost stopped. The darkness in my eyes went gray.

— And it’s always the same. The man sighed again over my sketches, and replaced the glasses; his eyes flashed large, as if he had seen something important. A momentary distortion.

For a long minute he gazed up at the ceiling, where the fan was slowly threshing flies. — They never stopped, you see. You must know something of that yourself. They never stopped adding in. Any time they thought of something new, they simply reached into air and added on another glyph. It’s worse than chaos, he sighed. — It’s infinity. It comes to the same thing in the end, doesn’t it?

He slumped, if this were possible, deeper in the dim brown heat, the rumples on his suit creasing through his face. — Did you know? I was trained as a chemist. For one year at University, before Nasser. Then the revolution came, and my family left, and I could study anything I wanted. We were all nationalists then, you know — very much so. And I decided that our heritage, our glorious gift to the human race, would be the more fitting study. But today — He pushed the scrap of paper back toward me. — Today I feel nostalgic for the benzene ring. You know the ring? A snake that bites its tail. That is perfection — none of this ringing in of signs from here and there and tomorrow: just carbon and hydrogen making geometry together.

— No. I am sorry, Doctor——: I cannot help you. I hope it was not important.

My second visit was to the Egyptian Library, and my work there was all in solitude, and all deliciously null.

And finally to the tourism board, where nothing consequential happened.

I am convinced more and more each day that I am dying. I left Cairo over the El Giza bridge, the bright Nile counterfeiting the morning sun. As I waited in the traffic in the Shari Al-Haram to make the left turn that would take me down to Route ø2, around me roared an endless procession of tourist buses, their windows black to opacity. What convinces me of my own hastening end is not the omnipresence of death around me — as I waited, a dog wandered into the traffic, rolled once as it was hit, righted itself, then went down again and was still — what convinces me is the persistence of my memory, as it replays before me isolated fragments of my life.

The struggle of the dog to right itself I had seen before, from behind the wheel of a ’58 Chevrolet on the boulevard that circled the city where I grew up. It was my car that struck the dog the second time — I could feel the thump of something solid beneath my feet, a brief rumbling roll, and then the motionless shape receding in the rearview mirror. I had refused to drive for a week after that, and my foster parents, angry — self-doubt they could never tolerate, I think because it confirmed their own uncertainty about me — threatened to revoke my driving privileges. And that dog — those dogs, the one warm beneath the Egyptian sun, the other still receding in the mirror — those dogs coalesce into a third, the one another set of parents had given me the week of my arrival in their home. I was twelve, I think, and alone in the house when a strange car stopped at the door, a woman handed me the collar with an aggrieved, — She ran out so fast.

The problem of digging a hole: twice I laid her in it, and twice I had to lift her out again and dig it deeper.

Within a year I was watching the since-familiar backhoe perform its obsequies over an equally parching soil, the thin blue of its exhaust the smoke of some small incineration as it backed the dust over that set of foster parents. Their car had been pinned beneath a bus. And in every case — I am omitting others — what struck me most was an emptiness in the visible world, a quality of light like the echo in an empty house, in every scene once inhabited by the—

What convinces me that I am dying is the way I maunder on, about dead pets, and foster parents, and myself. It is as if I have grown old — and I am not yet fifty. But these memories will not abate — they quicken, as if some part of myself hastens to become empty.

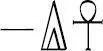

Come then, Thoth, provided with charm, quicker than greyhounds, fleeter than light. I am Khepera who produced himself upon the let of his mother. Untie the bandages, twice, which fetter my mouth. Behold, I collect the charm from the one with whom it abides, creating the gods from silence, giving the mother-heat to the gods, making forms of existence from the thigh of thy mother. Behold, this charm is given me from where it is, quicker than greyhounds, fleeter than light, more solid than shadow.

Читать дальше