The ushabti were, in later dynasties, an artistic convention: small, painted figurines in the image of the deceased and his servants, who were to do for him the onerous labor required in the Duat. They have long fascinated me, in the way all things Egyptian do; the attempt to make literal and concrete what we now conceive as only symbolic: this is essentially Egyptian. Before the opening of Nur-Mar’s tomb, it had never occurred to me to wonder what the origins of this abstracting process might have been in the case of the ushabti : if we looked back long enough, would we find the place where art lapses back into the flesh?

The Answerer in Nur-Mar’s tomb lay just inside the door. I do not know if there were theoretical or practical reasons for the location. Theoretically, I suppose, stationed near the door an Answerer would be placed so as to intercept anyone who entered with a task for the deceased. Practically, the issue is clearer: whoever stapled his fetters had made certain the chain would stop him short of the offerings of food and wine that filled the chamber just beyond.

There is this quality in any Egyptian tomb: they annihilate time. Whether it is in the clear preservation of the marks left by Nur-Mar’s Answerer in his last hours, or in the simple bouquet of dried flowers that we found atop the steward’s sarcophagus, in each case, with every trivial find, there is an overwhelming sense that these events stopped only moments before you entered. If the object of Egyptian funerary practice was to preserve the identity (the Ka, or Ba, or Kau, or Ku, call it what they would, and did) of the deceased, who is to say they did not succeed? Are there any other faces from the third millennium B.C.E. familiar to us now — not through stone or pigment, but the flesh itself, identifiable and individual, as Ramesses’ is in Cairo, or Nur-Mar’s is this moment in my memory?

When I was still a boy, almost forty years ago I won, as a prize in a national science competition, a two-week tour of Europe, in company with four dozen other prodigies. My memories of the trip are all decayed now into a series of hotel rooms with exotic fixtures and a damp smell, and a series of interminable bus rides. All lost now, except for one gray, drizzling morning in the valley of the Dordogne, when we descended into the caves of Lascaux. The image of a hand, silhouetted in a haze of charcoal, hangs above me to this day — too high for me to reach. Still I could tell the hand — the left — had been larger than my own. I felt almost a stroke from that hand, a touch on my skin that lingered. I emerged into the gray damp daylight of France and found the surface of the earth a hollow dream.

Never in my life have I felt so utterly alone, a boy of twelve, in a tour bus in Europe, a continent away from a land where I had no home.

As the works of the Egyptians bettered the hunting magic of the Magdalenian — the one hazy image of a hand ramifying, resolving out of chaos to become a face, a body swathed in linen, a room with furniture, almost a life — I am tantalized by the sense that, somewhere in the three millennia of their active seeking, someone in ancient Egypt may have done it. Someone may have reached a hand clear through the rock and pulled himself alive through death’s abiding wall.

With classes done, and no research expedition before me, I am reduced to examining a limited body of evidence. I have the lab results before me: copies; the originals the doctor retains, as if jealous of them. They show the chemistry of my blood, the skipping of my heart, the slow, dreaming drift of the EEG. All, the doctor said, were negative. He thinks I am a healthy man.

The X-ray shadows, CT slices, the MR angiograms all show the same object: my skull. The flaring void of nose, wide-staring sockets, the brain behind them in this view only indifferently visible, merely suggested by the net of veins, a fine haze upholding the invisible that is me.

Nothing reveals itself: no tumor sprouting at the center, no erosion mining the stem. I hold the gray films to my desk lamp, and the bright ghost of the bulb hovers a thumb’s width away from the obscuration in my eyes.

Nothing is there. But I wonder if, to other eyes, trained in mysteries I do not know, that net of nothing might reveal — what? I do not know, only that the thought of it sends horror through me: fear in my groin, a hand brushing cold up through my viscera. I feel the whispers almost audible, as though dust were blowing already through my heart.

APPLIED AND ENGINEERING PHYSICS

MAXWELL LABS

—— UNIVERSITY

Heard about your news. Think I can help.

Drop by here Fri. aft?

B.

“B” was Budge, who I knew had had his own application in. We are the same vintage, Budge and I, having been hired, reviewed, tenured and promoted in lockstep, as if he were my shadow or I his as we skipped up the steps of academic advancement together. Today I had learned who was whose shadow. Budge, I could tell from what the note did not say, had won his grant. Budge was through the door, and I had simply vanished from the track. Or was about to. When Budge came back from wherever he would spend his grant money, I would not be there to greet him.

This saddened me, more than I would have expected. I have no family, few friends. In my line of work — I cannot blame it on my line of work. But Budge and I, although our shared interests are few, and he has his family and his work beside, Budge and I have shared something like friendship this past decade. If friendship is the expectation that a certain face and voice will be there, met by chance and passed as easily, that was what we had. At the thought that one of our faces would be missing, I found myself growing what may have even approximated affection for Budge.

But that note! The cheery briskness of it — so like him, and so unlike my mood. Thought he could help . With what, friend B.? For a moment the exception I had made for Budge broke down, and I included him in my resentment against the well-funded world of the (as they like to say) hard sciences. I tossed the wad of paper in a corner of my office, and strode angrily out of doors.

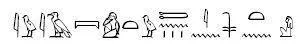

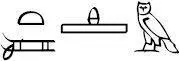

none who is outside know this spell, for it is a great mystery. Thou shalt not perform this in the presence of any person except thyself alone, for it is indeed an exceedingly great mystery which no man whatever knoweth.

These are the words of power to be spoken alone for entering into the underworld like a god. Thou shalt not speak these words, nor cause them to be spoken, in the presence of any person, for they are a great mystery, and the eye of no man soever must see them, for it is a thing of abomination for every man to know it. Hide it, therefore; the Book of the Lady of the Hidden Temple is its name.

— They’re in what? Astronomy? Agronomy you say, oh dear. Were their shoes clean? They won’t start tilling up the back yard, will they? What? Nematodes? They’re little worms, I think. Well I don’t think worms are preferable to animals, no.

Читать дальше