Rafik Schami

The Dark Side of Love

PRAISE FOR The Dark Side of Love

‘At last, the Great Arab Novel — appearing without ifs, buts, equivocations, metaphorical camouflage or hidden meanings. Schami’s book is exceptional not only in the scope of his ambition, but also in its ability to juggle a vast cast of characters in a complex structure. Despite its length, the book is a compulsive read.’

— The Independent

‘The picture of Syrian life and recent history is the great strength of this novel. Schami would not have achieved it without considerable skill… With its feuds, lovers, murders, villains and assorted heroes and heroines, this is a novel to enjoy and to ponder.’

— Washington Times

‘In The Dark Side of Love , Rafik Schami exploits all the resources of the classic realist novel and then goes a little further, forging a new form out of Syrian orality…Schami’s Mala is on a par with Márquez’s Macondo for colour and resonance. The Dark Side of Love illumines almost every side of love, as well as fear, longing, cruelty and lust. Darkness and light alternate like the basalt and marble stripes on Damascene walls, and the novel’s structure is just as strong. A book like this requires a less limiting title. I suggest something as expansive, as comprehensive, as War and Peace .’

— The Guardian

‘In Anthea Bell’s deft, witty translation, each of Schami’s 853 pages and 304 chapters is a pleasure to read.’

— The Observer

‘Anthea Bell’s translation is…remarkable, sure-handed and lapse-free. Schami is a wonderful storyteller.’

— The Nation

‘…a joyous book…Schami, a major international talent, has a broad range, from the scatological to the sexually comic to the painful’

— Publishers Weekly

‘A masterpiece! A marvel of prose that mixes myths, tales, legends, and a wonderful love story…’

— Die Zeit

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchase.

For two great women,

Hanne Joakim and Root Leeb

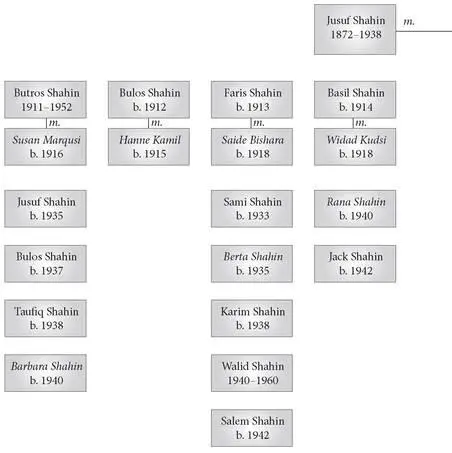

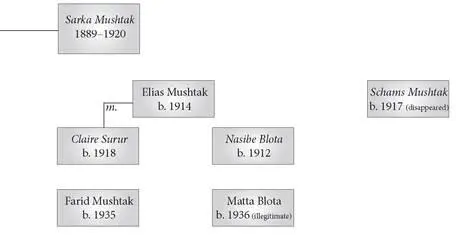

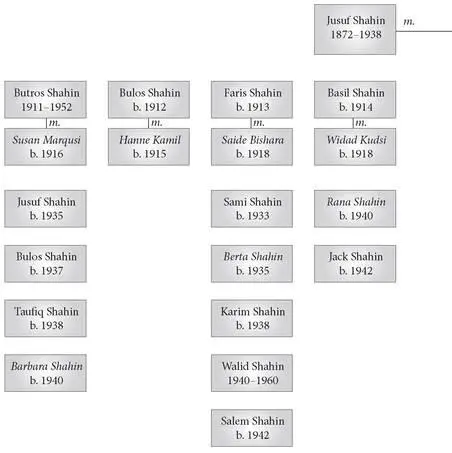

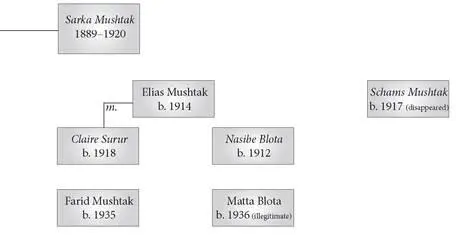

FAMILY TREE OF THE SHAHIN CLAN

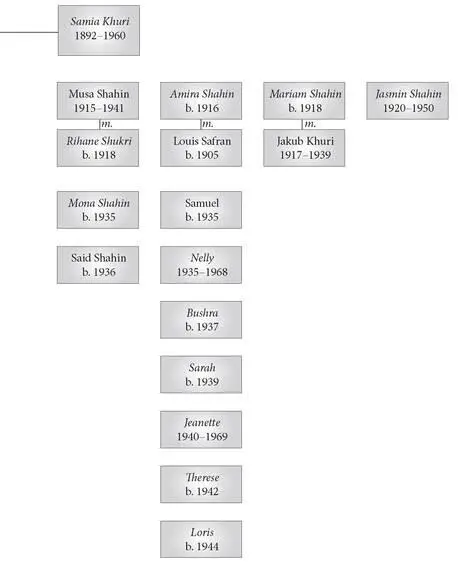

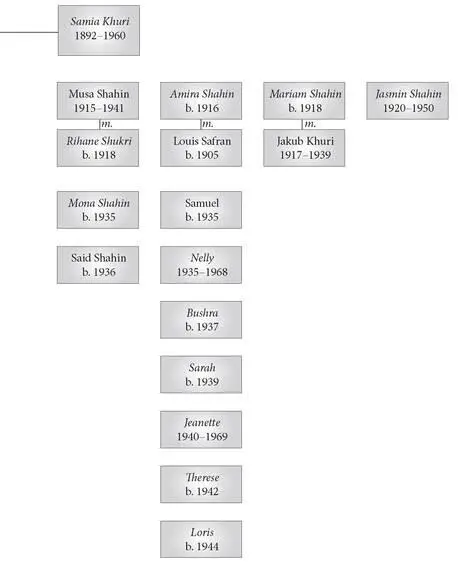

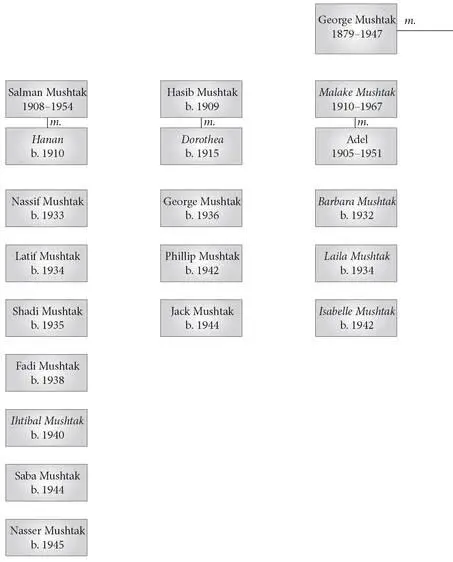

FAMILY TREE OF THE MUSHTAK CLAN

Olive trees and answers both need time.

DAMASCUS, SPRING 1960

1. The Question

“Do you really think our love stands any chance?”

Farid asked this question not to remind Rana of the blood feud between their families, but because he was feeling wretched and could see no hope.

Three days ago his friend Amin had been picked up as he left home and taken away by the secret police. Witch-hunts against communists had been in progress ever since the union of Syria and Egypt in the spring of 1958, and 1959 was a particularly bad year. President Satlan had made irate and inflammatory speeches denouncing communists and the Iraqi dictator Damian’s regime. There was no let-up as the year drew to its close; jeeps raced down the streets of the capital even by night carrying victims of the secret service. Their families were left weeping with fear. Tales were told of the bloodshed on New Year’s Eve. Rumours went from mouth to mouth, creating even more fear of the secret service, which seemed to have its informers in every home.

Love seemed to Farid a luxury that day. He had spent a few hours with Rana in his dead grandmother’s house, undisturbed. Here in Damascus, every meeting with her was an oasis in the desert of his loneliness. Very different from those weeks in Beirut, where they had hidden eight years ago. There, every day began and ended in Rana’s arms. There, love had been a wide and gentle river landscape.

His grandmother’s house hadn’t been sold yet. Claire, his mother, had given him the key that morning. “But your underpants had better stay on,” she laughed.

The sun was shining, but it was a bitterly cold day. Musty damp met him as he entered the house. He opened the windows, letting fresh air in, and finally lit the stoves in the kitchen and bedroom. Farid hated nothing more than the smell of damp, cold stagnation.

When Rana arrived just before twelve, the stoves were already red-hot. “Was it at your grandmother’s house we were going to meet, or in the hammam?” she joked.

As always, she was enchantingly beautiful, but he couldn’t shake off a sense of impending danger. While he kissed her, he thought of the Indian who sought safety from a flood on a rooftop and slowly sank to a watery death. Farid clung to his lover like a drowning man. Her heart beat against his chest.

In spite of the heat he was freezing, and her laughter — the wild laughter that kept breaking out of her and leaping his way — released him from his fear only for seconds at a time.

“What a model of proper behaviour you are today,” she teased him as they left the house again a few hours later. “Anyone might think my mother had told you to keep an eye on me. You didn’t even take off your…” And she uttered a peal of laughter.

“It’s nothing to do with your mother,” he said, wanting to explain it all to her, but he couldn’t find the right words. He walked along the narrow streets to Sufaniye Park near Bab Tuma beside her. Every jeep made him jump in alarm.

The President’s words boomed out from café radios, declaring implacable war on the enemies of the Republic. Satlan had a fine, virile voice. He intoxicated the Arabs when he spoke. The radio was his box of magic tricks. With a population that was over eighty percent illiterate, the opposition had no chance. Whoever controlled the radio station had the people on his side.

And the people loved Satlan. Only a tiny, desperate opposition feared him, and after that pitiless wave of arrests a strange anxiety held the city in its grip. But the Damascenes will soon forget it all and go about their business again smiling, thought Farid as they reached the park.

His fear was a beast of prey gnawing at his peace of mind. He kept thinking of Amin the tiler, who must now be suffering torture. Amin wasn’t just his friend. He was also the contact man between the communist youth group that Farid had been running for the last few months and the Party in Damascus. Only a few days ago he had assured Farid that he had gone to ground, cutting all the links leading to him. Amin was an experienced underground fighter.

Читать дальше