“Listen up, all of you young people. Listen up! I have something to say. Listen to me!” I looked at the assembled faces, in various stages of dishevelment. “It’s important that you understand what’s taking place around you—” And, realizing that this was a rather provocative assertion, I—

“Shut up, Dr. Van Deusen,” one of the kids called. “Answer a question or have a drink.”

“I will not shut up,” I said, my pride rising. “Please. Listen for a moment while I make some observations about current events.”

Another voice cried out, “Ever spent a sober day in your life? That’s your question!” Much snickering.

And then suddenly Skip was running off. My son was fleeing the scene. Owing, no doubt, to some tiny slight. I saw his handsome body, his stunningly handsome but empty-headed vessel, disappear into the darkness beyond the bonfire, a darkness that quickly enveloped whatever came its way. I picked up the nearest piece of driftwood that was at hand, and I closed in on the master of ceremonies, young D’Arcy, with intent to batter his person. But then it was there in my hands, the precious stick, and I could feel the stick calling to me. Above were the stars, wheeling in the dispassionate sky, and there was the hypnotic flickering of the fire, and before I had a chance even to think about what was happening, I was led by the stick into the night, following my son. I was hearing the ringing of the symphonies of strategic information, the contemporary symphonies, the symphonies of the civilian dead, and I said to myself that this was just absolutely wrong, and yet I felt my legs, my toes, my ligaments, my sinews, beginning the dance, the dance of death, on the shore of the beach, just out of the ken of the youngsters, who no doubt had begun to climb into one another’s arms. I began to cackle bizarrely. I knew arcane things that were lost to the historical record, and I was dancing and spinning like some Sufi master. I was a beacon on the shore. I was the sign, because there was always a sign, there was an indication, a first shot, a lantern in a window. It was clear! It was clear that I was meant to wake on the loggia, it may even have been my own loggia. I was meant to see Ed Thorne, double agent, meant to hear his story; these things lined up. The Omega Force knew that I would walk from the house at dawn. They knew, when they saw the Dance of the Stick, that it signaled the end of the West, the end of the American Century, and Ed Thorne told me what he needed to tell me, that they would come, the Omega Force, to set American against American. Ed Thorne was where he was meant to be, and when I heard what he had to say, I embarked on my researches, researches that brought me here, where, of course, I would repeat the Dance of the Stick, I would begin my foul dance, my ghoulish jig, and I would cast off my clothes. There was no other interpretation possible. It was I who was to invite in the Omega Force and its foreign agents. I was powerless to stop them, and in this dream I danced to the death, with the stick whose only wish was to be again in the sea, scrubbed by salts and storm tossed, and I would not bend to its will, and so we fought, the stick and I, a pitched battle, and the stick wrested me to its purpose, to be adrift, yes, as the great poets have always known, dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, it is sweet and fitting to die for your country.

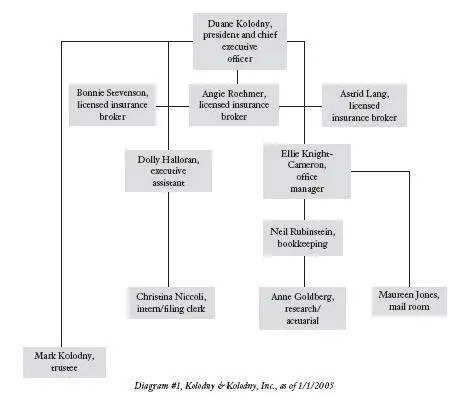

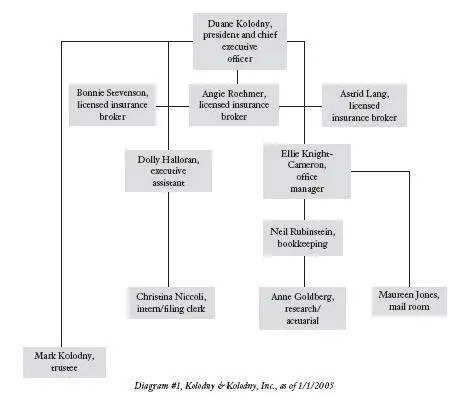

Ellie Knight-Cameronoversaw the suggestion box at Kolodny & Kolodny, a small insurance brokerage company, and in all the many years of discharging this humble task, she’d never come across a suggestion like the one she discovered Monday nestled in that cardboard container: If they’re going to close lanes on the parkway, they ought to actually repair the goddamned road .

K&K, as they abbreviated themselves, were located in the sprawling suburban municipality of Stamford, CT, a mile or so off the High Ridge Road exit of the Merritt Parkway, and for some years now this verdant stretch of pavement had been a maze of lane closures, especially west of town. The majority of K&K’s ten employees commuted into town against the prevailing traffic, and it was here that they often encountered the dreaded file of orange cones.

Without a doubt, this suggestion she found was reasonable. Excepting the split infinitive and the profane language. People complained about traffic. It was one of the things they talked about. Still, it was hard for Ellie Knight-Cameron to imagine what she, as office manager, was supposed to do about it.

Ellie had nothing much in the way of organizational power. In fact, the suggestion box existed mainly to enforce camaraderie at the K&K coffee station. Usually, therefore, the suggestions were kind of routine. Can we possibly get a blend with a little hazelnut in it? Just once in a while? Even if Dolly Halloran hated the vanilla hazelnut variety that Ellie later selected, the suggestion in this instance had met with general favor in the office, bringing good cheer to the lounge area.

Ellie Knight-Cameron was thirty-four, and she was a bit heavy for her age, or maybe it was just that despite years of workout regimens and exotic diets she had never once resembled a svelte, cosmopolitan type of woman, and she was a little self-conscious about this, despite her brown ringlets, which took an awful lot of work to maintain, and the mole above her upper lip that she thought was one of her best features. Her eyes were as gray as flagstones. She had an easy smile. People liked her, just not in that flinging-off-clothes kind of way.

Ellie’s hyphenated surname, to broach a sore subject, was the creation of her parents, who were as yet unmarried. These free spirits had met in the early seventies, out in the Sun Belt. The conception of Ellie Knight-Cameron, according to the story, had taken place during a festival gig by the venerable Allman Brothers Band. There’d been a particularly adventurous solo by Dickey Betts. In the far distance, beneath a tattered blanket, love conjoined the not terribly illustrious families Knight and Cameron.

Every Saturday, Ellie cleaned her apartment in Rye, and she started in the bedroom and worked her way north in order to avoid disturbing her cat, Nails, for the longest possible time. Ellie had ridiculously strong feelings about her vacuum cleaner, which was British, purple, and designed by an aeronautical engineer. Her excitement about vacuuming depressed her, though if you are going to be depressed about your enthusiasms, you should at least have a reliable vacuum cleaner as consolation prize.

On Saturdays she cleaned, and then she went to the organic market, and then she tried to arrange pastimes that involved her friends from the office or from college. She’d gone to school in the early nineties, those go-go years, as far away from the Southwest as she could get, which turned out to be Westchester County. What she liked to do with her friends from college — most of whom had crazy, arty ambitions — was play miniature golf. She also loved minor league baseball. At some hazy point in the future she intended to learn the tango.

Because Ellie Knight-Cameron was orderly in her habits and in her thinking, she’d been a natural hire for Kolodny and Kolodny. The name of the firm was a little misleading, actually, because there was only one Kolodny, and that was Duane, who had long ago hoped to lure his boy, Mark, into the business. Mark had gone into real estate instead, though he nonetheless presumed to inherit the business, perhaps so he could sell it off. Duane Kolodny had begun life as a contractor in Fairfield County, but he’d become fed up with the lawlessness and Darwinism of contracting. The gravel business was controlled by the mob, the cement business was controlled by the mob, the building permits were controlled by the politicians, the politicians were on the take, and so forth. Duane was a low-key person. He’d settled on insurance because it was pragmatic. He didn’t have to sell too hard; he just had to believe in his product. Which was another way of saying that Duane believed that you should take care of yourself and your family and move gingerly through life, on the lookout for trouble.

Читать дальше