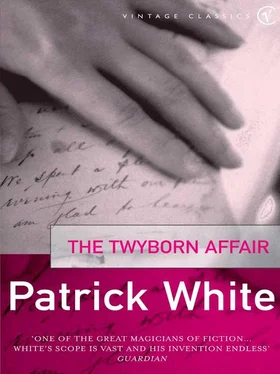

Patrick White - The Twyborn Affair

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Patrick White - The Twyborn Affair» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2011, Издательство: Vintage Digital, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Twyborn Affair

- Автор:

- Издательство:Vintage Digital

- Жанр:

- Год:2011

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Twyborn Affair: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Twyborn Affair»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Twyborn Affair — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Twyborn Affair», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Joanie called from the salon next door, ‘What are you doing, darling? I’ve been wondering whether we ought to take a present.’

‘Hadn’t thought about it. Could take along a case of champagne.’

‘Heavens, no!’ She was shocked to visualise Teakle lugging the case in their wake, through the overgrown garden, towards the dilapidated villa.

Curly had come out from the bedroom, and in spite of his tastelessness she was glad to see him, in his Harris tweed, exuding the scent of bay rum, so far removed from what Madame Vatatzes had referred to as ‘the smell of a man’. Mrs Golson sat smiling up at him from the Louis bergère , almost worshipful had he noticed.

But today Curly seemed moody and preoccupied. ‘What about pushing off?’ he asked, as though she had kept him waiting, and not the other way round.

Dear Curly, so reliable! When not submitted to the heavy demands of sexuality, in the context of what she understood as marriage, part duty, part economic, Joan Golson loved her husband.

‘That’s a stunner of a waistcoat, darling!’

But he did not seem to hear her remark. She ought to seduce him more often with little soothing compliments. Titillated by a thought, not quite innocent, and not quite reprehensible, she got up meekly enough and followed his broad tweedy back. Her mood of the moment was what she recognised as fragile. She might brush against him on entering the lift and they would enjoy a delicious reunion of loyalties under the hunchback’s malicious gaze.

It didn’t work out quite like that. Curly’s blenching finger pressed on the button repeatedly. ‘… out of order … antiquated …’ The voice made husky by alcohol and smoke vibrated in her.

‘Oh, darling, but how maddening!’ she protested. ‘It’s that man — the hunchback. He goes across and talks to the porter. I’ve caught him at it.’

It occurred to neither of them to take the stairs. Hadn’t they paid for the lift?

So Curly’s finger went on blenching as he pressed the button. Why was she so impressed by it? Far back, as a little girl, she remembered somebody showing her a witchety grub. But that was soft. As was she. Even so, she had squashed the grub. And had a bad dream about it. Oh dear, the liftman was to blame —Ange , no other — when they were expected at the Vatatzes’.

Suddenly the door of the cage opened to receive the Golsons. Ange was too detached to appear in any way censorious as he hung on the rope by which he functioned. The Golsons were standing at attention, at what might have been the prescribed distance from a liftman. Curly’s calves looked as substantial as one would have expected in a male figure of the better class, but Joan’s Papillon by Worth faintly shimmered and fluttered in the draught which entered from the lift-well.

They reached the rez-de-chaussée with such a bump that her hands grew hot inside her gloves and she clutched her bag as though she half expected a thief to snatch it. Inside the bag was the present she had hesitated to declare after squashing Curly’s suggestion of champagne. It was an antique amethyst brooch, framed, not in diamonds, but a garland of inoffensive brilliants: a charming little piece of jewellery, not made less so by the fact that Mrs Golson did not want it.

Then that bump. The hunchback’s hump. Ange!

But hadn’t they arrived safely? The door of the gilt cage opened. Curly Golson was getting out.

When Joanie told him, ‘Darling — I’m going up — back — only for a second. Wait for me in the lounge, won’t you?’

Halfway there, he could hardly have done otherwise.

Not only did Ange despise, he must have loathed her while hauling her back to the second floor. He could not understand that so much, almost her continued existence, depended on it.

‘ Merci ,’ she said. ‘ Vous êtes très gentil .’

What she could not have understood was that Ange despised her more for addressing him as no guest ever had at the Grand Hôtel Splendide des Ligures.

When Mrs Golson reappeared in the lounge she was wearing her tan Melton suit in place of the Worth Papillon. ‘Now,’ she enquired cajolingly, ‘are we ready?’

They went out to where Teakle was waiting to open the Austin’s doors.

She realised at once that she must look heavy, dull (perhaps she was) in her tan Melton. The hat sat too close to her heavy brows. She glanced about her nervously, licking her lips, adjusting the veil which bound the straight-brimmed hat to her head and made the whole effect more uncompromising.

Curly was in the driver’s seat.

‘Oh, do be careful, darling, won’t you?’

Did Teakle’s steadfast neck despise her as deeply as Ange the hunchback’s eyes?

Curly did not answer, and they started off. She rather enjoyed being terrified in their own motor, her husband at the wheel. Lulled by her terrors, she sank back into an upholstered corner, clutching her bag with the amethyst brooch which she might, she hoped, find the courage to offer Madame Vatatzes; it would suit her style perfectly.

As they swept through the grove of under-nourished pines, the stench from the salt-pans prevented Mrs Golson’s hopes aspiring much beyond the hatching of sooty needles, through which were revealed those other glimpses of enamelled gold and halcyon.

Very purposeful, he had come out on the front terrace and was calling, ‘Eudoxia! Where are you, E.?’ wearing the sun hat with the frayed brim, the spokes radiating from the crown, which made him look like an old woman. (E. said it didn’t; it suited him.)

Frustrated in his purpose, he returned through the house. Its structure seemed unstable this evening, rattling, groaning, trembling as he passed from front to back: the hovel which only an avaricious demi-Anglaise like Madame Llewellyn-Boieldieu would offer tenants poor enough to accept. Poor but not grateful, thank God! He had never been grateful for small mercies in any of his incarnations, not even on becoming what seemed like the last and withering twig of a family tree.

Passing a wall-mirror in the hall he saw reflected in the fluctuating glass, amongst the scales and blotches, this figure in the plaited hat. E. was wrong: it was the face of an old woman and a peasant. Not that the aged don’t tend to pass from one sex to the other in some aspects of their appearance. He didn’t feel that he had undergone a change. E. appeared to appreciate him as much as ever — to love? he sometimes wondered. (If only he could lay hands on that diary. No! There are wounds enough without the diaries; the wax effigies of lovers are stuck with countless pins.)

Angelos Vatatzes steadied himself on a rented console, worm-ridden to the extent that it threatened to crumble. (She would send them a French bill, by God!) This aged revenant in the peasant-woman’s hat, stuck with pins down the ages, from Blachernae to Nicaea, and down the map in travelogue to Smyrna and Alexandria. Athens? peugh! that haven of classicists and German nouveaux riches .

He remembered in his mother’s work-basket a little heart in crimson velvet bristling with pins. She was not all that good with her needle; she was not all that good. But he had loved to draw his finger through the labyrinth of pins, exploring the textures of the stabbed velvet. He would cower over the crimson heart, anything to postpone the walks along the Prokymea with Miss Walmsley, or Fräulein Felser, or Mademoiselle Le Grand — the governesses who had ruled his life in turn.

The women.

Of all those who had attempted to rule him, empresses, hetairai, his sister Theodora, Eudoxia his colonial ‘bride’, aunts, governesses, Anna his sainted wife, not so saintly in spite of the candles lit and the raw carrots nibbled at, only one had relieved him of the burden men carry, and that very briefly, long ago.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Twyborn Affair»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Twyborn Affair» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Twyborn Affair» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.