“We really believe

that all people are the same .

No one should be discriminated against,

just because he’s different .”

The stanza’s sarcasm hit Thorsten about the same time as a grenade-sized rock pegged him right above his eye. A thick rivulet of blood ran down his cheek and dripped from his chin.

The wind and the rioting kicked up Fatima’s ashes, scattering them in black swirls about the street. Klaudia, her fingers feverishly nimble, folded the suicide note into an origami paper cup complete with tuck-in flap and sprinted toward the last pile of ashes. Someone javelined a tree branch into the fracas; meant for the police, it boomeranged into my girl’s rib cage, knocking her down. A beer bottle landed at her feet. Unbowed, she scrambled through the broken glass. Thorsten turned to the Schwa and said, “This city really does need a new Berlin Wall, only this time it should be transparent,” then whipped his shirt off and stood in front of Stone’s wall.

“Heil Hitler!” he shouted, drawing the attention of all those who hadn’t already been transfixed by the life-sized tattoo of the führer inked across his muscular chest. It was an exact likeness, but if you looked closely you could see the mustache was a splotchy, fuzz-covered birthmark just above his belly button. Thorsten snapped a fascist salute, clicked his booted heels, and then stiffly goose-stepped to and fro in front of the wall like a storm trooper target in a Coney Island shooting gallery circa 1942.

Some bumptious carnival barker shouted out the rules.

“You have to stay on the curb. Legs and torso — ten points. Head shot — twenty-five points. Groin — fifty points. The swastika on his neck — one hundred points! Five rocks for one mark!”

The crowd loved it, and soon directed all of its energy to hitting the freak, pelting him with bottles, rocks, batteries, and whatever else they could find to throw. Whenever he was hit, Thorsten would shout a metallic “Bing!” and make an abrupt about-face.

The antics created the diversion that Klaudia needed to retrieve the ashes of her sister. And as we watched her scoop the flesh granules and bone chips into the paper urn, the Schwa turned to me. “You know, the bald-headed guy’s right.”

“About what?”

“About the wall. I can build a transparent wall — a wall of sound.”

The intensity of the stone throwing picked up. One of the blacks accused Thorsten of killing Fatima, and without a trace of bitterness in his voice, Thorsten kindly pointed out to them in so many words that in some moral court of law with broad psychosomatic jurisdiction, that accusation might be true, but the one thing they were all guilty of, black monkey and white superhuman alike, is that they all watched her die.

The stones stopped pinging against the wall.

Exhausted, Thorsten slumped to the ground, his Hitler tattoo covered in blood.

FOR HIM IT isn’t about the way a musician sounds. He could care less whether or not he or she has the “goods.” How they dress. For him the assemblage of a band is about some bizarre teleological holism whose main precept seems to be “the whole is a grater on some of its parts.”

He conducted his rehearsals like a basketball coach who, in order to emphasize conditioning and defense, puts his players through two weeks of grueling practice before they ever touch a basketball. He auditioned and rehearsed his band without once hearing a musician play.

“How do you know if someone can play without even checking out his embouchure?” I asked him.

“When you see someone holding the steering wheel at ten and two, exactly how they teach you in driving school, what’s the first thing you think about that driver?”

“That motherfucker can’t drive.”

“Okay then, I don’t need to see nobody hold, bow, blow, pound, sound no instrument.”

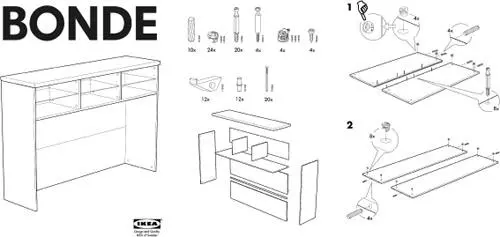

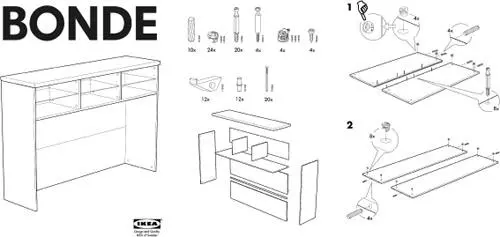

Instead he plotted their horoscopes, gave them psychometric tests for group compatibility, and made them sit through team-building exercises. My favorite part of the auditions was when he presented the musicians with his universal sheet music.

“But isn’t sheet music already universal?” they’d invariably ask.

“It is for musicians who can read music. What about the cats who can’t read music?”

Even the most forward-thinking musician would turn to the first page of “universal music” and freeze.

“Hey, man, Ikea instructions? I’m sorry, but I don’t get this.”

“Ikea’s instructions for furniture assembly are the closest thing we earthlings have developed that approaches a universal language. Okay, people, on page two, when we attach the left panel to the top shelf, I want the horns to come in on a D-flat major chord, and trombone, as you’re putting in the dowels, tonic the chord at the top. From there we’ll count sixteen bars, segue back to the intro, and nail the back panels down. Saxes, I want you to give out with that old Phillips-head-screwdriver, good-timey feeling. Now let’s play this fucking hutch, hit it on four.”

Most guys ran out the door screaming, but the ones who stayed were special.

There were like-minded guys like Willy Wow, a violinist whose music I’d greatly admired. His talents were retrograde in a very modern sort of way — he could make a violin sound like a synthesizer. During his job interview, the Schwa didn’t ask him what was the last book he’d read or what he felt was his worst quality. He looked at Wow’s mangled hand and said, “Tell me about Nam.”

“Vietnam wasn’t so bad. It’s what freed up my mind. I used to sit on top of the PX and listen to the sounds of battle. It was like going to the Laos philharmonic. Like sitting at Minton’s bar during a late night cutting session. It was the freest of free jazz. The Viet Cong would open up with this light-arms staccato. And the U.S. would return fire with artillery legato, mortar fire. Pound the hillside with 150mm and 175mm rondo and drop the napalm coda and blow away the whole stage, you dig? You’d think after that display of firepower there’d be no more shit for Charlie to play, right? Hills burned to a crisp. Not even a bird in the sky, much less a tree for one to fly out of. Any other normal motherfucker would have walked off the bandstand never to play again, but Charlie Cong let off three little mortar bursts, pop pop pop! And the cutting contest was over. They’d won the day and I knew they’d win the war. Right then and there I decided to sound like Vietnam.”

Needless to say Willy Wow was the band’s violinist, insomuch as there was a band. You never knew exactly who was in the band. The Schwa never summarily dismissed anybody or castigated his (and sometimes her) manhood and musicianship. Cats would simply know if they were wanted or not and would decide for themselves if they could hang. Permit me to introduce some of the regulars: Soulemané Eshun, a black-American bass player with an excellent bow technique and an annoying between-song habit of uttering cryptic African proverbs that only he and the Schwa seemed to understand.

“ Gbawlope nane a gipo ni ton ne a gipo ta-ton . Alligator says: We know a friendly from an enemy canoe.”

“Yeah, baby.”

“ Lã asike legbe meflo dzo o . A long-tailed animal should not attempt to jump over a fire.”

“Right on.”

On piano and percussion, Uli Effenberg. An expert aero-phone player, his eclectic collections of wind instruments included a cage of bees, a propeller hat, and a human skull, which when he waved it in the air produced the eeriest glissando through the eye sockets and missing teeth. Uli didn’t play the piano so much as he fucked with the piano. Sometimes he’d just move the stool back and forth, augmenting whatever the band was doing with the squeaks of the roller wheels and the slamming of the lid. He’d strike the pedals with a hammer; play the keyboard with a beach ball. Once, to the Schwa’s great amusement, he threw a mouse onto the piano strings, then went to sleep while the little white rodent comped the band.

Читать дальше