One night, on the anniversary of my father’s death, Marpessa and I drove down to Dum Dum Donuts for open-mike night. We took our usual seats, the far side of the stage, near the bathrooms and the fire extinguisher, bathed in the red haze of the EXIT sign. I located and pointed out the other exits to her just in case.

“Just in case of what? By some miracle somebody actually tells a funny joke and we have to run outside, dig up Richard Pryor and Dave Chappelle, and make sure their corpses are still in the fucking ground and it’s not black Easter? These fucking micro-Negro comedians they have today make me fucking sick. There’s a reason there ain’t no black Jonathan Winters, John Candy, W. C. Fields, John Belushi, Jackie Gleason, and Roseanne Barr out this motherfucker, because a large truly funny black person would scare the bejeezus out of America.”

“There aren’t many fat white comedians these days, either. And Dave Chappelle isn’t dead.”

“You believe what you want to believe about Dave. The nigger’s dead. They had to kill him.”

Someone at the club did make me laugh once. One time my father and I were there together when a stumpy black man, the new host, bounded onstage. He was unpaid-electricity-bill dark and looked like a crazed bullfrog. His eyes protruded wildly from his head like they were trying to escape the mental madness therein. And come to think of it, he was rather fat. We were sitting in our usual spot. Normally, except for when my dad was onstage, I’d read my book and let the sexual jokes and white people/black people bits wash over me like so much background noise. But this man-frog opened with a joke that had me crying. “Your mama been on welfare so long,” he bellowed, blithely holding the silver microphone like he didn’t need it and was there only because someone handed it to him backstage. “Your mama been on welfare so long, her face is on the food stamp.” Anybody who could make me put down Catch-22 had to be funny. After that, it was me who dragged Pops to open-mike night. If we wanted our usual seats, we had to get there earlier and earlier, because word was spreading throughout black L.A. that a funny motherfucker was hosting the open-mike nights. The donut shop would fill with black belly laughter from 8 p.m. — until.

This traffic-court jester did more than tell jokes; he plucked out your subconscious and beat you silly with it, not until you were unrecognizable, but until you were recognizable. One night a white couple strolled into the club, two hours after “doors open,” sat front and center, and joined in the frivolity. Sometimes they laughed loudly. Sometimes they snickered knowingly like they’d been black all their lives. I don’t know what caught his attention, his perfectly spherical head drenched in houselight sweat. Maybe their laughter was a pitch too high. Heeing when they should’ve been hawing. Maybe they were too close to the stage. Maybe if white people didn’t feel the need to sit up front all the damn time it never would’ve happened. “What the fuck you honkies laughing at?” he shouted. More chuckling from the audience. The white couple howling the loudest. Slapping the table. Happy to be noticed. Happy to be accepted. “I ain’t bullshitting! What the fuck are you interloping motherfuckers laughing at? Get the fuck out!”

There’s nothing funny about nervous laughter. The forced way it slogs through a room with the stop-and-start undulations of bad jazz brunch jazz. The black folks and the round table of Latinas out for a night on the town knew when to stop laughing. The couple didn’t. The rest of us silently sipped our canned beer and sodas, determined to stay out of the fray. They were laughing solo because this had to be part of the show, right?

“Do I look like I’m fucking joking with you? This shit ain’t for you. Understand? Now get the fuck out! This is our thing!”

No more laughter. Only pleading, unanswered looks for assistance, then the soft scrape of two chairs being backed, quietly as possible, away from the table. The blast of cold December air and the sounds of the street. The night manager shutting the doors behind them, leaving little evidence that the white people had ever been there except for an unfulfilled two-drink, three-donut minimum.

“Now where the fuck was I before I was so rudely interrupted? Oh yeah, your mama, that bald-headed…”

When I think about that night, the black comedian chasing the white couple into the night, their tails and assumed histories between their legs, I don’t think about right or wrong. No, when my thoughts go back to that evening, I think about my own silence. Silence can be either protest or consent, but most times it’s fear. I guess that’s why I’m so quiet and such a good whisperer, nigger and otherwise. It’s because I’m always afraid. Afraid of what I might say. What promises and threats I might make and have to keep. That’s what I liked about the man, although I didn’t agree with him when he said, “Get out. This is our thing.” I respected that he didn’t give a fuck. But I wish I hadn’t been so scared, that I had had the nerve to stand in protest. Not to castigate him for what he did or to stick up for the aggrieved white people. After all, they could’ve stood up for themselves, called in the authorities or their God, and smote everybody in the place, but I wish I’d stood up to the man and asked him a question: “So what exactly is our thing ?”

I remember the day after the black dude was inaugurated, Foy Cheshire, proud as punch, driving around town in his coupe, honking his horn and waving an American flag. He wasn’t the only one celebrating; the neighborhood glee wasn’t O. J. Simpson getting acquitted or the Lakers winning the 2002 championship, but it was close. Foy drove past the crib and I happened to be sitting in the front yard husking corn. “Why are you waving the flag?” I asked him. “Why now? I’ve never seen you wave it before.” He said that he felt like the country, the United States of America, had finally paid off its debts. “And what about the Native Americans? What about the Chinese, the Japanese, the Mexicans, the poor, the forests, the water, the air, the fucking California condor? When do they collect?” I asked him.

He just shook his head at me. Said something to the effect that my father would be ashamed of me and that I’d never understand. And he’s right. I never will.

Thank you to Sarah Chalfant, Jin Auh, and Colin Dickerman.

And a special thank you to Kemi Ilesanmi and Creative Capital. This book wouldn’t have happened without your faith and support.

Big hugs to Lou Asekoff, Sheila Maldonado, and Lydia Offord.

Shout-out to my family: Ma, Anna, Sharon, and Ainka. Much love.

Much respect, appreciation, and inspiration is owed to William E. Cross, Jr., whose groundbreaking work in black identity development, particularly his paper “The Negro-to-Black Conversion Experience” in Black World 20 (July 1971), I read in grad school and has stayed with me ever since.

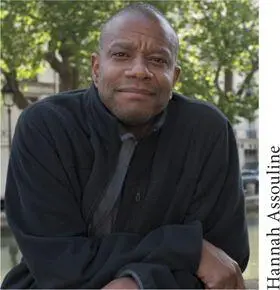

PAUL BEATTY is the author of the novels Slumberland, Tuff , and The White Boy Shuffle , and two books of poetry, Big Bank Take Little Bank and Joker, Joker, Deuce . He is the editor of Hokum: An Anthology of African-American Humor . He lives in New York City. Sign up for email updates here.