The Scriptological Review: A Last Letter from the Editor

• •

This is not a guide to good handwriting. You’ll find no dos and don’ts, no dotted lines here. If that’s what you’re looking for, try Cursive First , a workbook force-fed to me at the age of eight, when the nuns tried to mold my hand around the rubber pencil grip of conformity.

What you’re reading is the final copy of The Scriptological Review , a journal dedicated to the social analysis of handwriting. Our inaugural issue appeared two years ago, with a cover story titled “Slanty Signatures and Secret Turmoil: The Correlation Between High Cursive Slant and Low Self-Esteem.” In this, we analyzed a letter from John Wilkes Booth, whose cursive was brambled with signals that the lay reader would likely ignore, such as intraletter gaps and distended a ’s and o ’s.

If you’re still reading, then it’s likely that you are a subscriber and a scriptophile, but for the remaining fraction who have happened upon this issue on a bus seat or in a dentist’s office (or propping open a window, as I found my mother’s copy of Volume IV), let me introduce myself.

My name is Vijay Pachikara, and I am presently the editor of The Scriptological Review . My mom is listed on the masthead as “publisher-at-large,” but all she provides is the funding and the office space. I set up shop in her basement a year ago, and the commute from my bedroom couldn’t be better.

As long as my mom handles the funding, I don’t mind if she wants to while away her time with her boyfriend, Kirk Bäumler. Kirk is reliable and handy, like a good garden tool, a man of patience and resolve who once felled a cedar tree on his property and fashioned it into a dugout canoe. There may be much to admire about men like Kirk, but his handwriting tells another story.

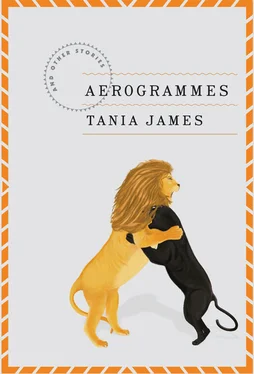

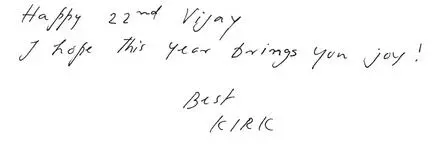

Exhibit A: Inscription from Birthday Card to Vijay from Kirk

Consider the narrowness of the e-loops, so sharp that they verge on lowercase i ’s, a recurring sign of neediness. Also note the castrated y .

I tried to persuade my mom to note as much while she was packing for their overnight trip to Nashville, but she was too busy fitting her belongings into her suitcase, as pleased as if she were assembling the last pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Kirk had urged her to come away with him to the Bahamas, but she refused to leave town for more than a night. I told Kirk that this was for the best, since I’d need her to make a few purchases from the photocopy store, where my credit card had been repeatedly declined. Kirk bit his lower lip, as he often does when I mention the Review .

Kirk has been sore ever since I wedged copies of the Review under the fenders of his employees’ cars two weeks ago. Apparently, the boardroom drones of Steak Shack Inc. have no sense of imagination or innovation, save the daughter of one guy, who called the number on the back of the magazine and asked if she could “sign up for the writing club.” Caitlin lived with her parents, said “um” a lot, and had less than a rudimentary comprehension of scriptology. Maybe she was bored. I was about to give her directions to my house when we were interrupted by what sounded like her father in the background: “Who’re you talking to, Cait? It’s been forty-five minutes.”

I heard her say, “No one …” before she promptly hung up.

A few days later, Kirk and my mom returned from Nashville. For half an hour, we bleeped through their digital photos: jubilant smiles, sad khaki shorts, both of them flanking a painted guitar twice their height. Her, in a rare moment of unabashed laughter, her hand at her heart, a gaudy rock on her finger, a ring I didn’t recognize. Him, standing beneath a sign that read GRAND OLE OPRY HOUSE, his arms spread wide as if waiting for a huge hug. (See Exhibit A, Neediness.)

“Well,” I said finally. “Well, great. Now my news. Mom, I’ve been thinking about the next issue of the Review —” I looked at Kirk pointedly. “Kirk, could you …” I glanced at the door. Kirk. Door. He sat there like a dog that didn’t know its own name.

He told me that he and my mom had gotten engaged.

“Yeah, I get it. I’m not surprised per se, if that’s the response you’re looking for. But congrats to you both.” My mom and Kirk traded glances, communicating in the not-so-secret parlance of married people. “Can we move on?”

Kirk moved on to trashing the Review . He recommended that I shut down operations, because he and my mom would be married soon. My mom would be the wife of the CEO of Steak Shack Inc., and the CEO could not afford phone calls like the one he’d received yesterday evening from a board member who had threatened to “take action” if he caught me communicating with his twelve-year-old daughter again.

Accordingly, my mom would be withdrawing all money from my budget, thus halting operations.

I stared at her. Wincing, she rubbed her chest, where her skin had lightly burned. “Did you know she was twelve?” my mom asked.

“Obviously not, Mom.”

“Why were you talking to her for forty-five minutes?”

“Because,” I said, looking only at her, “she was listening.”

This prompted a certain tone of voice my mom takes when she thinks I’ve lost the bread-crumb trail to normalcy. She asked if I needed to talk to Dr. Fountain, a heavily perfumed shrink I’d been seeing off and on throughout the year. It always made my face burn when she brought up Dr. Fountain in front of Kirk.

“As I was saying.” Maybe I repeated that phrase a few times while flipping the pages of my notebook, in which my scrawl was deeply, deliberately engraved. “The next issue will be dedicated to Dad.”

In our two years of circulation, The Scriptological Review has published a biannual personafile on historical or celebrity figures. Each signature, each strand of unraveled scripts, has led to analyses of the type rarely recorded in the humdrum biography or rise/fall/rehab biopic. Some highlights include Benjamin Franklin (“If Left Is Wrong, I Don’t Want to Be Right”), the Marquis de Sade (“Outer Loops and Inner Demons”), and Martha Stewart (“White Space 101”). In light of such figures, one might question the relevance of a personafile concerning my father, Prateep.

But this personafile has been long in the making, a goal of mine ever since the inaugural issue of the Review . My mission is to enlarge what my dad was reduced to, the five lines of an obituary, because we are survived not by memories but by what we leave behind in print or picture, and how are five stunted lines to span the breadth of a man’s life?

Take Exhibit B, a telling excerpt lifted from a letter sent by my father to my mother in the first two weeks of their marriage, after he had flown ahead of her to the United States. She would be following shortly, her first time leaving her family in Bangalore.

Exhibit B: Excerpt from Letter Sent by Prateep J. Pachikara to His Wife, Annamma

The rest of the letter is in Malayalam, and thus illegible to me, but scattered here and there with English words like “Johnny Carson” and “Cheerios.” These few words are pinholes of light in an otherwise impenetrable wall. I once asked my mom to translate the letter, and with a cursory glance, she returned it to me. “He says he has no friends except for Johnny Carson. He eats a lot of Cheerios. He hates his life.” She refused to say more and told me to remove my boxers from the dryer.

Читать дальше