Zakes Mda

The Heart of Redness

There is a real-life trader in Qolorha, whose name is Rufus Hulley, who took me to places of miracles and untold beauty. He must not be mistaken for John Dalton, the trader of The Heart of Redness, who is purely a fictional character. I am grateful to Rufus, and to Jeff Peires, whose research — wonderfully recorded in The Dead Will Arise and in a number of academic papers — informed the historical events in my fiction. As for the people of Qolorha, they will forgive me for reinventing their lives.

I wrote this novel in honor of new lives, among which I count my son Zukile, my daughter Zukiswa Zenzile Moroesi, and my daughter’s son, Wandile.

“Tears are very close to my eyes,” says Bhonco, son of Ximiya. “Not for pain. . no. . I do not cry because of pain. I cry only because of beautiful things.”

And he cries often. Sometimes just a sniffle. Or a single tear down his cheek. As a result he carries a white handkerchief all the time, especially these days when peace has returned to the land and there is enough happiness to go around. It is shared like pinches of snuff. Rivers of salt. They furrow the aged face.

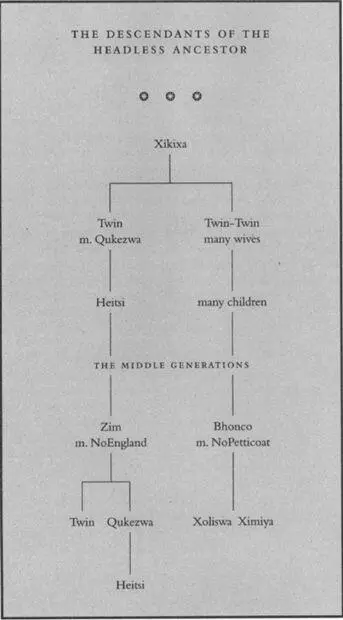

Bhonco is different from the other Unbelievers in his family, for Unbelievers are reputed to be such somber people that they do not believe even in those things that can bring happiness to their lives. They spend most of their time moaning about past injustices and bleeding for the world that would have been had the folly of belief not seized the nation a century and a half ago and spun it around until it was in a woozy stupor that is felt to this day. They also mourn the sufferings of the Middle Generations. That, however, is only whispered.

Bhonco does not believe in grieving. He has long accepted that what has happened has happened. It is cast in cold iron that does not entertain rust. His forebears bore the pain with stoicism. They lived with it until they passed on to the world of the ancestors.

Then came the Middle Generations. In between the forebears and this new world. And the Middle Generations fleeted by like a dream. Often like a nightmare. But now even the sufferings of the Middle Generations have passed. This is a new life, and it must be celebrated. Bhonco, son of Ximiya, celebrates it with tears.

NoPetticoat, his placable wife, is on the verge of losing patience with his tears. Whenever someone does a beautiful thing in the presence of her husband she screams, “Stop! Please stop! Or you’ll make Bhonco cry!”

She dotes on him though, poor thing. People say it is nice to see such an aged couple — who would be having grandchildren if their daughter, Xoliswa Ximiya, had not chosen to remain an old maid — so much in love.

It is a wonderful sight to watch the couple walking side by side from a feast. He, tall and wiry with a deep chocolate face grooved with gullies; and she, a stout matron whose comparatively smooth face makes her look younger than her age. Sometimes they are seen staggering a bit, humming the remnants of a song, their muscles obviously savoring the memory of the final dance of a feast.

The custom is that men walk in front and women follow. But Bhonco and NoPetticoat walk side by side. Sometimes holding hands! A constant source of embarrassment to Xoliswa Ximiya: old people have no right to love. And if they happen to be foolish enough to harbor the slightest affection for each other, they must not display it in public.

“Tears are close to my eyes, NoPetticoat,” snivels the man of the house, dabbing his eyes with the handkerchief.

“A big man like you shouldn’t be bawling like a spoiled baby, Bhonco,” says the woman of the house, nevertheless putting her arm around his shoulders.

A beautiful thing has happened. They have just received the news that Xoliswa Ximiya, their beloved and only child, has been promoted at work. She is now the principal of Qolorha-by-Sea Secondary School.

Xoliswa Ximiya is not called just Xoliswa. People use both her name and surname when they talk about her, because she is an important person in the community. A celebrity, so to speak. She is highly learned too, with a B.A. in education from the University of Fort Hare, and a certificate in teaching English as a second language from some college in America.

“They will not accept her,” laments NoPetticoat, as if to herself.

“But she is a child of this community,” says Bhonco adamantly. “She grew up in front of their eyes. She became educated while others laughed and said I was mad to send a girl to school.”

“They will say she is a woman. Remember the teacher who left? He was a man, yet they didn’t accept him. They made life very difficult for him. How much more for a woman?”

“They made life difficult for him because he was uncircumcised. He was not a man. How could he teach our children with a dangling foreskin?”

“I tell you, Bhonco, they won’t accept her. They will give my baby problems at that school!”

“She is not a baby. She is thirty-six years old. And if they don’t accept her it will be the work of the Believers. They are jealous because they don’t have a daughter who is as educated,” says Bhonco, making it clear that the discussion is terminated.

It had to come back to the war between the Believers and Unbelievers. They are in competition in everything.

The early manifestation of this competition happened a few years ago when the Ximiyas bought a pine dining table with four chairs. The family became the talk of the community, since no one else in the village had a dining table those days. But Zim, of the family of Believers, had to burst the Ximiya bubble by buying exactly the same dining table, but with six chairs. That really irked the son of Ximiya and his supporters.

Since then the war between the two families has become a public one. Their good neighbors await with bated breath the next skulduggery they will do against each other.

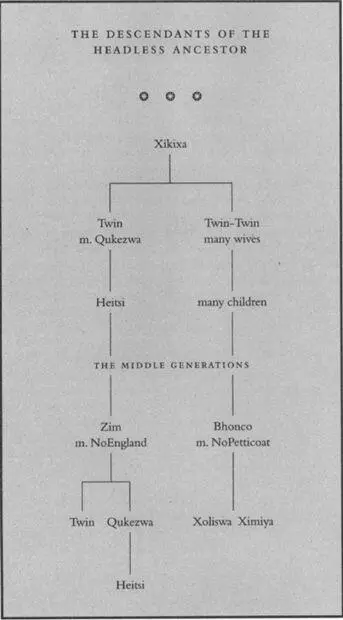

The Cult of the Unbelievers began with Twin-Twin, Bhonco Ximiya’s ancestor, in the days of Prophetess Nongqawuse almost one hundred and fifty years ago. The revered Twin-Twin had elevated unbelieving to the heights of a religion. The cult died during the Middle Generations, for people then were more concerned with surviving and overcoming their oppression. They did not have the time to fight about the perils of belief and unbelief.

But even before the sufferings of the Middle Generations had passed — when it was obvious to everyone that the end was near — Bhonco, son of Ximiya, resurrected the cult.

He does not care that only his close relatives and himself subscribe to it. Nor does it matter to him that people have long forgotten the conflicts of generations ago. He holds to them dearly, for they have shaped his present, and the present of the nation. His role in life is to teach people not to believe. He tells them that even the Middle Generations wouldn’t have suffered if it had not been for the scourge of belief.

Beautiful things are celebrated not only with tears. So Bhonco tells his wife that he will go to Vulindlela Trading Store to buy a tin of corned beef. NoPetticoat laughs and says he must not use the promotion of her baby as an excuse. He needs something salty because he had a lot to drink at the feast yesterday, and now he is nursing a hangover. Whoever heard of sorghum beer giving one a hangover? Bhonco wonders to himself.

“While you are away I’ll go to the hotel to see if they have work for me,” says NoPetticoat as she adjusts her qhiya turban and puts a shawl over her shoulders. But her husband cannot hear her, for he has already walked out of their pink rondavel.

Читать дальше