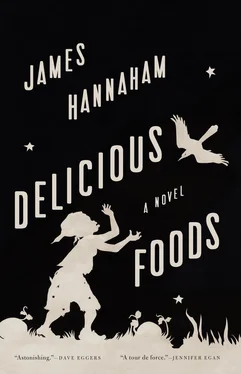

James Hannaham

Delicious Foods

The worm don’t see nothing pretty in the robin’s song.

— Black proverb

After escaping from the farm, Eddie drove through the night. Sometimes he thought he could feel his phantom fingers brushing against his thighs, but above the wrists he now had nothing. Dark stains covered the terry cloth wrapped around the ends of his wrists; his mother had stanched the bleeding with rubber cables. For the first hour or so, the divot-riddled road jostled the car, increasing the young man’s agony, and he clenched his teeth through the sickening pain. Steering the vehicle with his forearms stuck in two of the wheel’s holes, Eddie couldn’t keep the Subaru from wobbling and swerving, and he feared the police would notice, pull him over to find that he had no license, and arrest him for stealing the car.

When he came to smooth asphalt, he turned right for no good reason, and after a few miles he saw a sign that proved what he and his mother had believed all along. Louisiana, he breathed. Almost six years in that place. To finally see evidence of his whereabouts momentarily eased his mind, but he had to keep going. He had only a faint memory of where the farm ended, and he couldn’t tell if he’d driven himself closer to the center, where someone might capture or kill him, or away toward freedom.

The gas-pump symbol on the dash turned red around the time he saw signs for Ruston. The owner of the Subaru had left his wallet by the gearshift, and Eddie found $184 in it, which to his seventeen-year-old mind meant he could pay for gas to almost anywhere.

First he went to Houston to look for Mrs. Vernon, but to his surprise, the windows and doors of her bakery had wooden boards nailed over them. That such a responsible woman had either failed or fled implied nothing good about the fate of the neighborhood these past six years. The only other safe place he could think to go was his aunt Bethella’s house. He slithered into an oversize sweatshirt to hide his injuries from her, but when he got to the door, he could tell that someone else lived at her address — all the patio furniture had changed, toys lay jumbled on the cushions, and a wooden sign next to the mailbox said THE MACKENZIES. Since it was too early to knock, he left, but at the curb he spoke with a neighbor who remembered her. She told him Bethella lived in St. Cloud, Minnesota. His aunt had told him that she might move, but not that she had gone so far. Hadn’t she said that she would call with the address? Was that before the phone got cut off?

In the abstract, Eddie knew that Minnesota was far away, but he couldn’t fathom the distance. The name St. Cloud sounded to him like heaven. His confusion only rose when a sleepy Texan trucker in a Stetson made getting there sound easy. You take 45 North till you hit 35, the dude said. Then just keep on 35. That there’s the ramp to 45 just yonder.

To save money, Eddie stopped only at Tiger Marts or On the Gos to get gas and snacks and use the john. If he saw a police car in the lot, he kept going. If a truck-stop bathroom needed a key, he’d go someplace else. After he got his zipper down the first time, he couldn’t pull it up. He thought of sleeping, but whenever he pulled into the corner of a parking lot and lay down in the backseat, fiery twinges of pain snaked up his arms into his neck. When he asked for help squeezing the gas pump, strangers would knit their eyebrows together, shocked eyes asking, This kid can drive without hands? He’d say nothing but bristle and think, I got here, didn’t I?

On the third morning, feeling safer after reaching Minnesota, the pain now a dull throb, he sat nursing a Coke in a diner off I-94, the Hungry Haven, a cozy place decorated in beauty board, with citrus remnants cooked onto the silverware. In the smoking section, a lone waitress sat facing away from the counter, her body slack as any customer’s. An urgent story resounded on the TV behind her. Some rock star in Seattle had shot himself dead. She stared at the highway as if it were God. It took Eddie a while to get her attention, but once he did, she snapped to and hopped over, spine straight, pen behind her ear.

Do you mind, miss? Can’t light it myself, he said, his request muffled by the cigarette he’d wrangled from its box and picked up with his mouth. He grinned and raised his elbows, meeting the woman’s eyes with his own.

Oh! Of course, right, she said, her wide eyes failing to mask her surprise. She struck a match and he inhaled the fire through the cigarette. Gonna be a nice day, she announced, like something profound. Let me know if you need anything else.

Her name tag said SANDY, pinned onto a dingy pink dress with a gray apron wrapped around it. Under her nasal tone something cared so strongly that Eddie moved sideways down the bench a little, crablike, to avoid the power of her interest, fearing that she might get to know him against his will. Sandy turned away.

Actually, I’m looking for work, Eddie blurted out to her back. He wasn’t looking yet, really, but suddenly he needed her kindness, superficial or not, craved it beyond his ability to stay distant. Near here, he went on. He didn’t think Bethella would let him sponge for long. If at all. She might not even care that he’d lost his hands — she’d probably blame his mother.

Sandy turned and the glow left her face. Hmm, she said. What kind?

Of work can I do? You’d be surprised. Fixing stuff. Computers. I also do carpentry, wiring, odd jobs.

Doubt spread across her face, and Eddie thought he could almost read her mind: Now how can this boy do that in his condition?

He sat up. I can do just about anything I set my mind to, he said, pouring brightness over her hesitation. God makes three requests of His children: Do the best you can, where you at, with what you got now.

That’s beautiful, Sandy said. I bet your mama told you that.

Eddie smiled because he knew his mother would never have said such a thing — he’d picked up the saying from Mrs. Vernon — but then it occurred to him that Sandy would think the smile meant Yes, Mama sure did. Confirming that her fantasy of his life was the truth would make her more likely to help. After a brief chat, he told her his full name and she wrote it down on a wet napkin. He figured he’d never hear from her again.

It took Eddie a day and a half to find Bethella. He asked one of the few black pedestrians where he could find a beauty shop, adding that he meant to find his aunt. The pedestrian asked his aunt’s name, which she didn’t recognize, and then recommended he try Marquita’s Beauty Palace on St. Germain. To get there, Eddie had to drive across the Mississippi River — he read the sign aloud as he crossed. It astounded him to think that this was the same river as the one near his hometown, Ovis, Louisiana, and that it flowed as far as he had just driven. Seeing the same river here helped him adjust. The Great River wasn’t wide or grand in Minnesota, but it didn’t fill him with the same panic as it had back home — it had less to do with death. The past didn’t slither through this shallower water; he didn’t imagine any drowned ghosts staring up from the riverbed or bobbing out of culverts, their googly eyes asking Why?

St. Cloud pacified him — its evenly spaced suburban homes reminded him of a balsa-wood city he’d seen in a children’s book. Even its housing complexes sat comfortably beyond tall, healthy trees and sprawling plots of grass, and though a hundred Day-Glo toys might lie upturned on one driveway, the next several lots would have neatly arranged yards already flashing a few green shoots, while here and there a crocus forecast a pleasant spring. It felt more like home than Ovis, a place he hadn’t seen in almost a decade.

Читать дальше