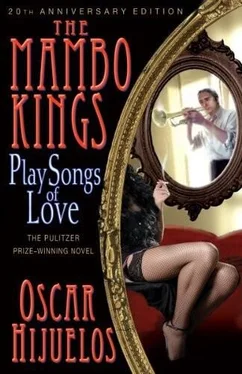

Now the narrow entranceway of Orchestra, where those records were made, was blocked off with boards, its windows filled with the remnants of what had become a dress shop; a few manikins were leaning backwards against the glass. But back then he and the Mambo Kings used to carry their instruments up the narrow stairway, their enormous string bass always banging against the walls. Beyond a red door marked STUDIO was a small waiting room with an office desk and a row of black metal chairs. On the wall, a corkboard filled with photographs of the record company’s other musicians: a singer named Bobby Soxer Otero; a pianist, Cole Higgins; and beside him, the majestic Ornette Brothers. Then a photograph of the Mambo Kings all dressed in white silk suits and posed atop a seashell art-deco bandstand, the photograph crisscrossed with looping scrawls.

The studio was about the size of a large bathroom and had thickly carpeted floors with corkboard- and drape-covered walls, and a large window looking out on 125th Street. It was hot and airless on warm days, without air-conditioning or ventilation when they were recording, save for the rusty-bladed fan that sat atop the studio piano, which they’d turn on between numbers.

Three big RCA ball microphones in the center of the room for vocals, another three for the instruments. While making their records, the musicians would remove their shoes and walk quietly about, careful not to stomp their feet during the recording session, as this would get picked up as “thumps” on the microphones. No laughing, no breathing, no whispering. The horn players would stand to the side, the rhythm section — drummers and string bass and pianist — on another.

Cesar and his brother Nestor side by side, the Mambo King playing the claves (the wooden instruments making the 1-2-3/1-2 clicking sound) or shaking maracas, strumming a guitar. Sometimes Cesar played trumpet melodies with Nestor, but usually he stepped back and allowed his brother to take his solos in peace. Even so, Nestor always waited for his older brother’s signal, a nod, to begin. Only then, would Nestor step forward, his mournful solos flying like black angels through the group’s lavish orchestrations. With that, Cesar returned to the microphone or the pianist took his own solo or the chorus sang. Sometimes these sessions lasted until the early morning, with some songs coming easily, and others played again and again until throats grew hoarse and the streets seemed to blur in a phantasm of lights.

Like his music, the Mambo King was very direct in those days. He and Vanna had just been out to dinner at the Club Babalú and Cesar said to her, as she chewed on a piece of plantain fritter, “Vanna, I’m in love with you, and I want the chance to show you what it’s like to be loved by a man like me.” And because they’d been throwing down pitchers of the Club Babalú’s special sangria, and because he had taken her to a nice movie — Humphrey Bogart and Ava Gardner in The Barefoot Contessa —and because he had gotten her a fifty-dollar modeling fee and an expensive ballroom dress with pleated skirt so she could appear between himself and his younger brother on the cover of “Manhattan Mambos ’54”; and perhaps because he was a reasonably handsome man who seemed earnest and knew, as wolves know, exactly what he wanted from her — she could see it in his eyes — she was flattered enough that when he said, “Why don’t we go uptown?” she said, “Yes.”

Maybe it was on that chair that she had first set down her fine ass while going about the delicate business of hoisting up her skirt and unsnapping her garters. Coyly smiling as she rolled down her nylons, which she afterwards draped across the chair. He lay down across the bed. He’d taken off his jacket, his silk shirt, his flamingo-pink tie, stripped off his sleeveless T-shirt, so that his top was bare — save for a tarnished crucifix, a First Communion gift from his mother in Cuba, hanging from a thin gold chain around his neck. Off with the lights, off with her wire-reinforced Maidenform 36C brassiere, off with her Lady of Paris underwear with the flowery embroidered crotch. He told her exactly what to do. She undid his trousers and gripped his big thing with her long slender hand, and soon she was unrolling a heavy rubber prophylactic over it. She liked him, liked it, liked his manliness and his arrogance and the way he threw her around on the bed, turning her on her stomach and onto her back, hung her off the side of the bed, pumping her so wildly she felt as if she was being attacked by a beast of the forest. He licked the mole on her breast that she thought ugly with the tip of his tongue and called it beautiful. Then he pumped her so much he tore up the rubber and kept going even when he knew the rubber was torn; he kept going because it felt so good and she screamed, and felt as if she was breaking into pieces, and, boom, he had his orgasm and went floating through a wall-less room filled with flitting black nightingales.

“Tell me that phrase again in Spanish. I like to hear it.”

“Te quiero. ”

“Oh, it’s so beautiful, say it again.”

“Te quiero, baby, baby.”

“And I ‘ te quiero ,’ too.”

Smugly, he showed her his pinga, as it was indelicately called in his youth. He was sitting on the bed in the Hotel Splendour, hidden by the shadows, while she was standing near the bathroom door. And just looking at her fine naked body, damp with sweat and happiness, made his big thing all hard again. That thing burning in the light of the window was thick and dark as a tree branch. In those days, it sprouted like a vine from between his legs, carried aloft by a powerful vein that precisely divided his body, and flourished upwards like the spreading top branches of a tree, or, he once thought while looking at a map of the United States, like the course of the Mississippi River and its tributaries.

“Come over here,” he told her.

On that night, as on many other nights, he pulled up the tangled sheets so that she could join him on the bed again. And soon Vanna Vane was grinding her damp bottom against his chest, belly, and mouth and strands of her dyed blond hair came slipping down between their lips as they kissed. Then she mounted him and rocked back and forth until things got all twisted and hot inside and both their hearts burst (pounding like conga drums) and they fell back exhausted, resting until they were ready for more, their lovemaking going around and around in the Mambo King’s head, like the melody of a song of love.

Thinking about Vanna threw open the door to that time. The Mambo King found himself walking arm in arm with her — or a woman like her — into the Park Palace Ballroom, a huge dance joint on 110th Street and Fifth Avenue. That was his favorite place to hang out on his nights off, when he wanted to have fun. It would feel good to make an entrance with a pretty woman on his arm, a tall blonde with a big heart-shaped ass: Vanna Vane, splendid in a bursting black sequin-disk-covered number that blinked and wobbled clamorously when she’d walk across a room. He’d strut in beside her, wearing a light blue pinstriped suit, white silk shirt, light sky-blue tie, his hair slick and his body scented with Old Spice, the mariner’s cologne.

That was the thing in those days: to be seen with a woman like Vanna was prestigious as a passport, a high-school diploma, a full-time job, a record contract, a 1951 DeSoto. Dark-skinned men like Nat King Cole and Miguelito Valdez would turn up at the dance halls with blond girlfriends. And Cesar liked to do the same, even though he was a white Cuban like Desi Arnaz. (Why, he knew of this fellow, hung around in the clubs, who made his brunette girlfriend dye her pubic hair blond. He knew it because he’d taken her to bed once, when she was still a brunette, and then later, on the sly, he’d talked her into going somewhere with him, maybe the Hotel Splendour, where he planted a kiss on her navel and slid her panties off, slipping his tongue into the sweetness of her new, improved golden Clairol hair.) Moving through the ballroom crowd, he liked to watch the heads turning in admiration as he and his girl would make their way to the jammed bar. There he’d play the sport and buy his friends drinks — in the 1950s, rum and Cokes were the rage — joking and telling stories until the orchestra broke into something like the “Hong Kong Mambo” or the “Mambo de Paree” and he would take his girl back out onto the floor and dance.

Читать дальше