One of the boys, in the memorial photographs, had had a look in his eyes. Startled. As though the flash of the camera had taken him by surprise. As though he had known what was coming. The plaque said he was seventeen. You wondered what had happened. If he really had seen it coming. You’ve seen pictures of an old fort on a nearby island, the walls spotted with bullet marks, the entrances surrounded by shallow craters, and you imagined that boy crouching on the roof, or in the shaded interior, holding an old rifle in his shaking hands, listening to the encircling approach of men and equipment through the trees and bushes outside. You imagined him listening to their taunts. Wiping the sweat from his eyes. Avoiding the glances of the men left with him. Wondering how they had all ended up in that place, what they could have done to avoid it, what they were going to do now. Knowing there was nothing they could do.

A bus stops on the road at the top of the hill. The others must be getting on it by now, rummaging in their pockets for change and wondering how much longer you’re going to be. When you get back they’ll all be sitting out on the terrace, watching the yachts gathering in the harbour for the evening, listening to children playing up and down the back streets behind the apartment. You’ll take a beer from the fridge, hold the cold wet glass against the back of your sunburnt neck, and ask where the bottle-opener is. No one will be able to find it at first, and then it will turn up, under a book or a leaflet, or in the sink with some dirty plates, and you’ll flip the top off the bottle and take your seat with the others.

You swim some more, and there’s a feeling in your arms and legs as though the muscles have been peeled out of them, as though the bones have softened from being in the water too long, and you can’t find the energy to pull yourself forward at all.

You turn on to your back for a few moments. A rest is all you need. It’s been a while since you swam in open water like this, that’s all. A few moments’ rest and you’ll be able to swim to the rocks, to the steps, and climb out. You’ll be able to hang a towel over your pounding head until you get your breath back, dripping water and sweat on to the sun-bleached concrete, feeling the warm solid ground beneath you. You’ll be able to gather your things and make your way along the path, pulling on your shirt as you go. And the grasshoppers will still be calling out, and the air will be thick with rosemary and pine. The sandy soil of the path will still kick up into dusty clouds around your ankles. Your swimming trunks will be dry by the time you get to the top of the hill, and you won’t have to wait long for a bus. And while you stand there the sea will be as calm and blue as ever when you look down over it, drifting out to the horizon, reaching around to other bays, other beaches, other villages and towns, other swimmers launching out into its warm and gentle embrace.

And this will be a story to tell when you get back home, sitting under the patio-heaters at the Golf Club bar, looking out over the cold North Sea and saying it was a nice holiday but I nearly never made it home. Or later this evening, sitting at some pavement café in a noisy bustling square with tall glasses of cold beer, telling the story of how you’d almost swum out too far. How you’d had to dump the snorkel and mask. It was a close one, you’ll tell them. I called out but you didn’t hear. No one heard. Best be more careful next time, someone will probably say; even when the water looks calm there are still currents. Just because it’s warmer than back home doesn’t mean you can treat it like a swimming pool, they’ll say, and you’ll laugh and say, well, I know that now. And everyone will go quiet for a moment, thinking about it, until the waiter comes past and you order another round of drinks. And raise a silent toast to all the good things. The cold wet glass against the back of your sunburnt neck. The trace of her fingers, the soft wet bite of her lips. The juice of an orange spilling down your chin. Music, and dancing, and voices colliding in the warm night air.

You swim, and you rest. It won’t take long now. It’s not too far. You look up, past the headland and into the next bay along, and you swim and you rest a little more. Sometimes it happens like this.

Supplementary Notes To The Testimony Of Appellants B & E

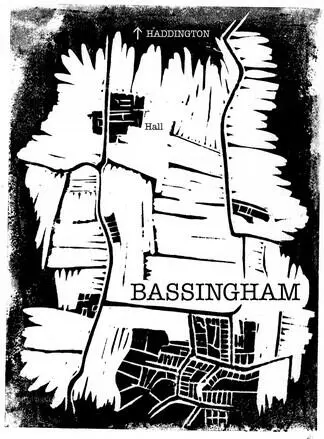

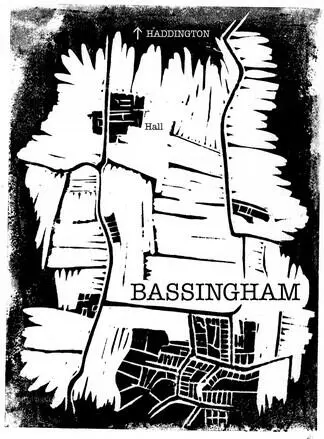

Bassingham, Haddington

Back to contents page

i. Bassingham is a small village situated on the eastern bank of the River Witham, upstream from the major population centre of Lincoln. Agriculture was the major economic activity in the area, along with a range of small businesses associated with the sector: repair-yards, feed merchants, packing-houses and the like. The agriculture was predominantly arable, with a range of cereal, salad and root crops; there was also, prior to the period in question, a sizeable dairy and beef industry in the area, with cattle grazing mainly taking place on the low-lying fields along the river valleys. The population of Bassingham, when last surveyed, stood at 700, although the figure is probably now lower. There are two public houses, a church, and a bridge which carried the road towards Thurlby and Witham St Hughs. The rebuilding of the bridge is nearing completion at the time of writing. There are currently no official school buildings. During the period in question, with formal education suspended due to security concerns, the majority of children in the area were engaged in assisting older family members with the movement and management of livestock, in addition to more informal occupations such as swimming, ball-sports, courtship rituals and evacuation drills.

ii. Not proven.

iii. Haddington is a small hamlet of residential and agricultural buildings, situated approximately 300 metres north of the River Witham and a mile south of the ancient Roman road to Lincoln, known as the Fosse Way, which is now a major highway. Satellite imagery suggests that the walk from Haddington to Bassingham would take approximately 45 minutes, via either the Thurlby Road or Bridge Road bridges. It would also be possible, and within the stated context significantly safer, either to cross by the weir at the end of Mill Lane or to ford the river at one of its narrower points and make one’s way to Bassingham’s outskirts through the low-lying fields in which, reportedly, the crops sometimes grew to above head-height.

iv. The veracity of a claim such as this is not within this report’s remit. It is sufficient to observe that, in common with many similar accounts, this section of the transcript serves to demonstrate that the appellants perceived a high enough level of risk for their covert evacuation to be organised by older members of the community.

v. The nearest government military installation to Bassingham/Haddington is at RAF Waddington, six miles to the east; this equates to approximately 90 minutes’ walk, or 30 seconds’ flight time. Squadrons based at RAF Waddington are predominantly surveillance-oriented; the nearest ground-attack aircraft are based instead at RAF Coningsby, which is a further twenty-one miles — or 60 seconds’ flight time — to the east. Aircraft based here include the Eurofighter Typhoon, which carries the Paveway IV laser-guided bomb system (using a modified Mk-82 general-purpose bomb with increased penetrative abilities and an optional air-burst fusing system) as well as the Mauser BK-27 revolver cannon and AGM-65 Maverick, AGM-88 HARM, Storm Shadow and Brimstone air-to-surface missiles.

vi. Satellite imagery does in fact indicate that between Haddington and the river lie the remains of what is believed to be a former manor or grange, with a series of raised earthworks, ditches, ponds and a former medieval dovecote providing few clues as to the original form or function of the building, or to the identity of its once wealthy inhabitants. There is however no current evidence to support these claims of recent excavation, or burial.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![Нил Уолш - Единственное, Что Имеет Значение [The Only Thing That Matters]](/books/393630/nil-uolsh-edinstvennoe-chto-imeet-znachenie-the-onl-thumb.webp)