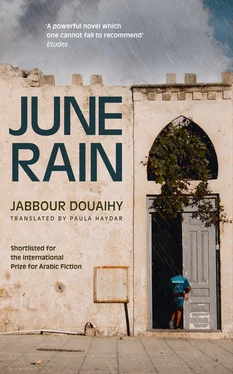

Jabbour Douaihy

June Rain

They didn’t tell us what happened until the next day. They let us sleep through Sunday night unawares — upstairs, on the top floor of the east wing, where the smell of the nearby river and the dawn calls of the muezzins entered through the wide open windows. There we distracted ourselves on hot June nights by watching the few cars that passed through the market streets and observing the arguing of the lazy, mischievous, loud-mouthed boys getting back at the diligent kids with thick glasses who teachers were always putting on a pedestal.

It was almost seven o’clock when the headmaster entered the classroom followed by the school doorman. Those of us who were fighting back sleep, and there were many on that Monday morning, lifted our heads. Frère Ambroise would not have brought in Jamil al-Raasi if this were about the poor results of the mathematics exam, or what he might have heard about our plans to mix pop lyrics into the Latin chants of the local Maronite and Catholic families who attended church at the school on Sundays. Those were the kinds of infractions the headmaster dealt with in that French of his, studded with the harshest words. His tone confused us, even more than the names of the tropical birds and desert reptiles he would dole out to us, in plural and in singular form.

Jamil, despite his slight build and silent nature, was the school’s eyes and its link to the outside world. He negotiated with demonstrators when their chanting leaders in the front lines pushed too close to the school gates across from the Coppersmith Souk in the hope that for once the school would be shut down and the students allowed to join in their angry protest against the Tripartite Aggression on Egypt. He lent money to students in emergencies and relayed brief messages to the boarders from their parents: ‘Eat well, Anise, and don’t sneak out of school to go and hang around in the streets. It’s not safe out there…’

When parents came to the city to shop or to pay their mortgages at the government offices, they would visit Jamil to give him things to deliver to us, like goat’s cheese or aniseed fritters. It was to him and him alone that such matters were entrusted, matters we felt were impossible to convey in French. That language, whose symbols we struggled to decipher in those books with the depressing illustrations and which rolled fluently off the tongues of the Frères in their black habits, referred, in our view, to things from another world that had no counterpart in ours. As for our own affairs and our own names, they had their own language that was part of them and came from them. And that is why it was Jamil al-Raasi who leaned back against the doorframe and said in a lifeless tone, ‘Barqa kids, pack your books…’

Those were the kinds of things he was entrusted with — announcing to the Muslim children an extra day of holiday just for them on Eid al-Adha, or to the Orthodox Christians at Easter, or to dismiss the kids from the snow-covered mountain villages two hours early. His announcements were met with shouting and whistling, as the teachers in charge momentarily relaxed their supervision. As for us ‘Barqa kids’ the news of our early dismissal struck the older ones among us speechless and the younger ones with a silent joy that the week had been messed up already, along with concern about the bad news that was no doubt going to sting us soon.

When we heard Jamil al-Raasi’s announcement, we didn’t rush around making a racket and collecting our things the way the recipients of such announcements usually did. Despite our silence, Frère Ambroise couldn’t help barking out his orders — ‘No noise in the stairwells!’ — mostly in French, confirming our suspicions that he only pretended not to understand Arabic to trick us.

The headmaster seemed to be trying to restore some of the school’s decorum, which had been compromised when he conceded to set us free, most likely after hearing how vitally necessary it was for us to leave. A sudden silence fell upon the hundreds of day students who were flooding into the school. They looked us up and down, as if seeing us for the first time as we crossed the playground with our belongings on our backs. We tramped past the little wooden stage, the place where Davidian the photographer had got us to line up alongside our teachers for our commemorative class pictures. We, the children of Barqa, wouldn’t be appearing in the end of year photos that ill-omened year of 1957. As he led us to the gate, Jamil remained silent, despite our impulsive questioning and our little hands tugging on his shoulders and nearly tearing his jacket, until finally, like someone ridding himself of a heavy responsibility, he said, ‘Ask Maurice.’ The bus driver.

Jamil was right to hand the matter over to Maurice, because the bus driver was from our village. Jamil, on the other hand, was from a distant village way out in Akkar, near the Syrian border. Maurice was the one who took us to our families, once a month at most, whenever the school was pressured to release us. The longer we stayed away from the vicinity of the town, the safer our parents felt we were. As Maurice sat watching us get on the bus, he gripped the steering wheel and stared into space.

‘Maurice!’

He too did not answer.

We called out to him, we questioned him using every tone of voice. Maybe he didn’t want to say anything within hearing distance of Jamil al-Raasi — a ‘stranger’ — who was supervising our departure and making sure we behaved as we crossed the few metres between the school grounds and the bus, parked beside the gate out in the nearby circle that Jamil was also in charge of supervising.

‘Maurice! What’s going on? Where have you come from?’

Twenty questions, each with its own particular urgency, failed to pry a single word out of Maurice, or even a wave towards the back of the bus or one of his usual glances in the mirror to make sure we were under control and all accounted for. It wasn’t until the last one of us had climbed aboard the bus that Jamil al-Raasi shut the rear door, repeating timidly to us like someone about to reveal everything he knew, or as if offering one final word of advice before saying his last goodbyes, ‘Take care of yourselves.’

The moment Maurice heard the door slam shut, he started the engine and took off, without making the sign of the cross. We didn’t fight over the window seats or push our way towards the long bench seat at the back of the bus where we liked to put our feet up and stretch out, trying to undo all those hours of sitting properly in the classroom.

At first Maurice was preoccupied with getting out of the city. He seemed to be using the difficulty of passing through the narrow streets as an excuse for not answering our incessant questions. Trying to justify not answering us, it seemed, he showed excessive agitation as he swerved to avoid hitting the fruit carts and liquorice juice vendors or the acrobatic delivery boys cycling through the traffic delivering orders of hummus or fava beans to their customers. That day Maurice kept quiet, didn’t gripe about all the chaos in the wheat market. Nor did he curse the porters who obstructed the road, heaving under their loads. He didn’t even lose his patience when a horse cart got stuck between the produce crates and blocked traffic. All of that, in his opinion, and as he so often preached to us about, was clear proof of the inability of Arabs to win wars, though he never indicated whether he was happy about their losing or pained by it. But that morning Maurice appeared unable to speak as he laboured with his short arms to turn the steering wheel around the successive sharp bends on our way up towards the American School. At any rate, we felt that, for the first time in the entire history of his driving us to our homes, Maurice was not in a hurry. Nor were we, as I recall.

Читать дальше