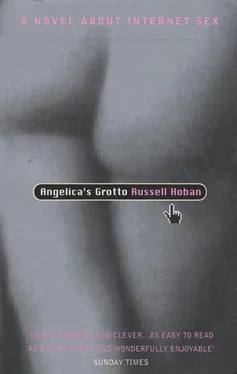

Russell Hoban - Angelica's Grotto

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Hoban - Angelica's Grotto» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2000, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Angelica's Grotto

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

- Жанр:

- Год:2000

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Angelica's Grotto: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Angelica's Grotto»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Angelica's Grotto — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Angelica's Grotto», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He withdrew into his video collection, surfacing intermittently to watch Yuletide films in which Germans spoke broken English before being blown up by Lee Marvin and Telly Savalas. Even when the TV was turned off, Christmas carols, seasonal piety, and adverts for computer games leaked out of it and spread in a greasy puddle on the floor. Walt Disney manifested his undead self in various ways, sometimes sliding under the door as a mist, sometimes like a bat at the window or a wolf howling in Fulham Broadway. On Christmas Day a grey sky squeezed out a thin snowfall on which fresh dog turds stood out sharply.

Klein phoned Melissa several times and got her answering machine; he left messages but she never phoned him back. Sometimes he imagined her writhing naked in steamy orgies; sometimes he imagined her in the bosom of her family somewhere in the provinces, eating and drinking and sleeping with whoever was handy without a thought for him.

When the partridges had left the pear trees and the lords had ceased to leap, Klein emerged blinking and unshaven into the Christmas-New Year interval. The ghost of New Year’s Past now came to visit with clanking chains of memory and action replays of champagne, soft words, and kisses. Sometimes it hunkered down beside his bed and improvised sad songs of happy times departed; sometimes it rocked back and forth and moaned.

36 Gynocracy

‘How am I going to get through the time between now and the auction?’ said Klein to himself. ‘I don’t want to call Melissa until I have something to tell her, some bargaining power.’

He went to his computer, put his last Klimt page up on the screen. ‘Sorry,’ he said, ‘I’m no longer interested in Klimt.’ He went to his shelves and got The Drawings of Bruno Schulz, edited and with an introduction by Jerzy Ficowski. The first drawing he turned to was the cliché-verre engraving, Eunuch with Stallions. There was the naked woman prone on the tousled bed, indolently looking back over her shoulder as a white stallion, rampantly crouching, licked her bottom. Rearing up beside the white stallion was a black one. Little pariah-men watched from behind the bed, and in front of it the dwarfish eunuch, face black with lust and impotence, grovelled on the floor.

‘Is there anything new to be said about Schulz and sado-masochism?’ said Klein. ‘Is there in all men a secret desire to abase themselves at the feet of a woman who has contempt for them? Or is it simply that I’m naturally depraved and losing control of myself?’

Wild thing, said Oannes.

‘Are you taking the piss or what? You think I should lose control more than I already have? Speak, Oannes.’

No answer.

‘I’m getting tired of your one-liners,’ said Klein. ‘Why do you always chicken out of a real conversation?’

No answer.

Klein turned the pages, looking at drawing after drawing of the ghastly little wretch at the feet or under the feet of beauties naked and clothed who spurned him. He turned back to the introduction, in which Ficowski explained:

The mode of expression and the subject matter of this early cycle of engravings [The Book of Idolatry] are governed by the principal idea of ‘idolatry’ — veneration of a Woman-Idol by a totally submissive Man-Slave. That motif dominates all of Schulz’s graphic works — the proclamation and celebration of gynocracy, the rule of a woman over a man who finds the highest satisfaction in pain and humiliation at the hands of his female Ruler. Suffering does not kill but nourishes and intensifies love.

‘Of course,’ said Klein, ‘I’m not in love with Melissa: what I feel for her is nothing more than some kind of kinky impotent old-man thing that makes me replay that night with her over and over — what she did and what she said when I was face-down on the floor. The feel of her nakedness against my back! Her not-to-be-questioned authority, her physical strength, and her utter contempt!’

He put on a new CD, Garbage: ‘I’m only happy when it rains,’ sang Shirley Manson, sounding naked under her mac, ‘I’m only happy when it’s complicated.’

‘Me too,’ said Klein.

37 A Firm Hand

Days passed, each one with hundreds of hours in it, but Klein held to his resolution and did not phone Melissa. She phoned him one rainy evening, and at the sound of her clear academic voice all of his senses instantly replayed the unforgettable night. ‘Hello,’ he said, choking a little over the word.

‘Hello, Harold,’ she said, sliding a leg between his, tango-fashion. ‘I haven’t heard from you for a while.’

‘I know. I’ve had nothing to tell you yet and I know you don’t like me to waste your time.’

‘Ah! I think I may have been a little unkind when I saw you last. I’m not really a very nice person but I was nice to you that time I came to your place, wasn’t I?’

‘Are you playing with me?’

‘Yes, but you like it when I play with you, don’t you?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you were serious about funding my study, right?’

‘Absolutely. I told you I’d be working on it and I am.’

‘How?’ Her leg was around his waist, pressing him to her.

‘I’m not ready to tell you.’

‘But why make such a secret of it?’

‘I’m superstitious — I don’t want to jinx it by saying anything before it actually happens.’

She moved her leg so that her knee was in his crotch. ‘Before what happens?’

‘Can’t say yet.’

‘Harold,’ a slight pressure from the knee, ‘you’re not getting beyond yourself, are you?’

‘Oh dear, I hope not.’

With her thigh between his legs she lifted him a little. ‘Because it seems to me you’re being very naughty.’

‘I don’t mean to be but I can’t help it.’

Supporting him with one hand, she bent him back and brought her face close to his. ‘Some discipline might be in order at this point, eh?’

‘I know I need a firm hand to keep me in line.’

‘Yes, and the sooner we get you sorted, the better. When should I come over?’

‘Whenever you like — your time is scarcer than mine.’

Her hand was clamping the back of his neck. ‘How about right now?’

‘Whatever you say,’ said Klein.

When she rang off he felt giddy from the swiftness of the changes in the dance. It suddenly seemed terribly important to have the right music going when she arrived — tango wasn’t right for the occasion nor were rock, pop, jazz, or blues. He rejected various modern albums, at length chose Olympia’s Lament as sung by Emma Kirkby to the accompaniment of Anthony Rooley’s chittarone.

There were two versions of it on the CD, one by Monteverdi and the other by Sigismondo d’India. ‘ Voglio, voglio morir, voglio morire,’ began the Monteverdi: ‘ I want, I want to die, I want to die,’ sang Olympia, abandoned by Bireno on a rocky and pitiless shore. ‘Another one of Ariosto’s hard-done-by women,’ said Klein, listening briefly to the measured outpouring of her woe and deciding that it would go better with the evening’s activities than the more overt emotion of the d’India. ‘For our visiting feminist,’ he said.

He scanned the room, moved The Drawings of Bruno Schulz from the littered couch to the little table by the TV chair and left it open at the spread with Eunuch with Stallions on the left; on the right was The Feast of Idolaters, in which a whole grovel-group queued up on hands and knees to kiss the foot of a seated woman who was showing a lot of leg.

He was busy adjusting lamps and rearranging clutter when the doorbell rang. Melissa was wearing a long and baggy black pullover, her usual black stockings, thigh-high shiny black boots, and nothing else that he could see. Klein moved back from the door to let her in but when he moved towards her again in the hall she stopped him with an outthrust arm. ‘Don’t try to approach me as an equal, little man — it’s time for your spanking. Trousers down!’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Angelica's Grotto»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Angelica's Grotto» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Angelica's Grotto» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.