‘That’s right.’

‘You didn’t want that?’

‘You don’t take anything for granted, do you?’

‘I can’t afford to in my line of work. Did you or didn’t you want him to do to you what he did to Monica?’

‘I didn’t want him to do that, OK?’

DeVere was looking at the first page of ‘Monica’s Monday Night’. ‘Where and when had you arranged to meet Angelica?’

‘In Surrey Street at a quarter past ten.’

‘That’s where and when Monica was pulled into the van on her Monday night.’

‘I know.’

‘Didn’t that set any alarm bells ringing in your head?’

‘OK, when we made the date to meet in Surrey Street on a Monday night my first thought was that I might be getting into a Monica situation.’

‘So you weren’t all that surprised to see Leslie, were you?’

‘All right, at some level I might’ve been half-expecting it.’

‘And how were you feeling about the possibility?’

‘Scared, but curious.’

‘Curious about …?’

‘About how it would be.’

Dr DeVere was looking at ‘Monica’s Monday Night’ again. ‘Here Monica’s recalling newspaper stories of rape,’ he said, ‘then “She sees her thighs being forced apart; she makes an O with her lips, imagines the taste of semen on her tongue and the sweat of brutal men on filthy mattresses in evil-smelling rooms.” Were your thoughts running along those lines?’

‘Look, I’m not homosexual.’

‘I never said you were. People have all kinds of thoughts and that’s what we’re talking about.’

‘All right — my thoughts were running along those lines, the same as Monica’s, OK? Tell me, do you enjoy rubbing people’s noses in what they don’t want to have their noses rubbed in?’

‘I’m not rubbing your nose in anything; if that’s how you experience this it might have to do with the judgements you pronounce on yourself. All I’m trying to do is clear away the bullshit. Do you think we can do that?’

‘I’ll make an effort.’

‘People have all kinds of wants and needs and they have different ones at different times. Sometimes I want to listen to Beethoven quartets; sometimes all I want to hear is Argentinian tangos.’

‘I know you’re trying to make me feel more comfortable, Dr DeVere, but sometimes I’m afraid of what’s in my mind.’

‘Mr Klein, you have got to learn that you’re not on trial for anything. Everybody has a public life and a private one; the private one is full of things that are not public business. This double life is part of the human condition. Nobody needs to know where you flick your bogies and I don’t need to know all your private thoughts but we’ve got to establish some points of reference. Can you say exactly what it is that you want from Angelica and/or Leslie?’

‘I’m not sure yet. Right now what I want is her real name and I’m meeting Leslie tonight to get it.’

‘Why does that require a meeting?’

‘Because I have to give him money for it.’

‘Ah! The question, “Do you know what you’re doing?” springs to mind.’

‘Yes, I do. Oannes hasn’t been very forthcoming but I’ve talked it over with myself out loud. I really need to know who this woman is and why she’s doing what she’s doing.’

‘But Oannes has been forthcoming — he said, “Gone.” It might be useful to consider the implications of that word.’

‘I have, but I’d rather this Angelica person didn’t get away with being inexplicable. Have you seen the Antonioni film, Beyond the Clouds?’

‘No.’

‘In it there’s a filmmaker who travels around looking for characters and stories he can use. He has an encounter with a young woman who says to him, “It’s better if I speak to you plainly. Whatever you have in mind, I’d rather tell you who I am: I killed my father — I stabbed him twelve times.” We learn that she was acquitted but we never find out why she did it. This young woman is played by Sophie Marceau. Have you ever seen her?’

‘No.’

‘It wouldn’t matter what she’d done — she’s irresistible. She and the filmmaker sleep together, after which we see him through the window waving goodbye and that’s it. We never find out why she stabbed her father twelve times.’

‘Maybe we don’t need to know.’

‘I think Antonioni left it that way so it would stay in our minds, unexplained and unforgettable. That’s OK in a film but this is real life and I need to know more about this woman who calls herself Angelica.’

‘Just remember that if a scene in a film doesn’t work they can take it out

‘But real life is full of scenes that don’t work and we’re stuck with them. I know what you’re saying.’

‘Be careful.’

‘I will.’

Oannes — deep-sea habitat — K getting in over his head? wrote Dr DeVere in Harold Klein’s folder. Then he slowly and carefully perused ‘Monica’s Monday Night’.

‘In Klimt’s painting Tod und Leben,’ wrote Klein, ‘we see the very essence of his mature art; he has emerged from the decorative excesses of his gold period and is now coming to grips with unadorned elementals; the grinning skeleton, ein Knochenmann (bone-man), in his cross-bedecked robe, wielding the red sceptre of his authority, feasts his empty eye-sockets on the living naked bodies (all but one with closed eyes) intertwined in love and procreation. In successive revisions of this painting from 1911 to 1916 Klimt changed the background to a non-space and removed the aura once worn by Death. This same Death, naked and lascivious, looks out, unseen, from the ardent and indolent bodies of the half-dressed and undressed women in his ghostly sketches: every one of these drawings is a matter of life and death; the snaky lines barely contain the transience of the flesh that cries out against the death that waits within, lusting for consummation.’ Klein sighed. ‘And in me too a death is growing; it’s getting bigger as I get smaller, and when we’re both the same size we’ll change places — I’ll be my death and my death will be me.’

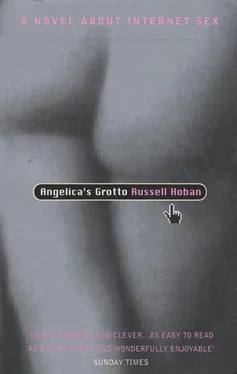

He quit the word processor, went to the Internet, and put Angelica’s Grotto up on the screen. ‘Why can’t I be dignified in my old age?’ he said, and patiently trawled through the galleries in which Angelica did every possible thing in every possible position with partners of both sexes, singly and in groups. With his face close to the screen he lusted after the firm flesh in the photographs, flesh that could be touched and tasted, flesh in which Death nestled, cosy and warm and smiling. ‘What good is this?’ he said. ‘Why am I wearing out my eyes on it? Why am I insulting my intelligence with it? I’m pathetic’

Do something, said Oannes, speaking for the first time in a voice that seemed not to be Klein’s own. Was it a deeper voice? Were the words somewhat slurred?

‘I am doing something — I’m meeting Leslie at ten o’clock and he’s going to tell me Angelica’s real name. OK?’

No answer.

‘If that’s not enough, just tell me what else you want me to do.’

No answer.

‘All right, have it your way: maybe I’ll go out and do something really crazy and it’ll be on your head. Is that what you want?’

Klein dug around in a box where he kept tools and other ironmongery and came up with a hunting knife bought for a long-ago camping trip. He went down to the kitchen and sharpened it. Then he put it in a pocket of a shoulder bag, got his jacket, and went out.

At ten o’clock the van with Leslie at the wheel pulled up in front of where Harold Klein was standing in Surrey Street. Klein walked around to the driver’s side. ‘I’ve got the two hundred,’ he said. ‘Have you got a name for me?’

Читать дальше