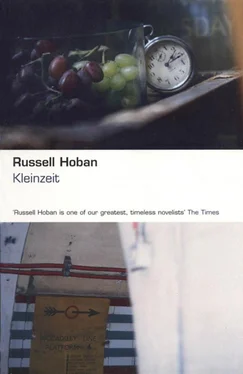

Russell Hoban - Kleinzeit

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Hoban - Kleinzeit» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, Издательство: Bloomsbury, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Kleinzeit

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Kleinzeit: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Kleinzeit»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Peloponnesian War

Kleinzeit — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Kleinzeit», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Don’t know,’ said Redbeard, hugging himself, making himself small. ‘I’m scared.’

‘What of?’

‘Everything.’

‘Come on,’ said Kleinzeit, ‘I’ll buy you coffee and fruity buns.’

Redbeard followed him up to the street still looking small. ‘No fruity buns, thanks,’ he said at the coffee shop. ‘No appetite.’ He looked nervously about while he drank his coffee. ‘The lights in here don’t seem bright enough,’ he said. ‘And the street’s so dark. Nights usually look brighter than this with the street lights on and all.’

‘Some nights are darker than others,’ said Kleinzeit.

Redbeard nodded, hunched his shoulders, huddling away from the night outside the window.

‘You live on straight busking?’ said Kleinzeit.

Redbeard nodded. ‘Mostly,’ he said. ‘Plus I nick a few groceries and the odd thing here and there. Keep going, you know.’ He nodded several times more, shook his head, shrugged.

‘The yellow paper,’ said Kleinzeit, ‘is it a special kind? Where do you get it?’

‘Ryman. 64 mill hard-sized thick din A4. Duplicator paper, it says on the wrapper. Best leave it alone, you know. It’s nothing to muck about with.’

‘Lots of people must do, though,’ said Kleinzeit. ‘People in offices. If it’s duplicator paper it’s being used all the time to duplicate things, I should think.’

‘Duplicating!’ said Redbeard. ‘No danger in that. Listen, I want to tell you about it …’

‘No,’ said Kleinzeit, ‘you mustn’t.’ He hadn’t expected to say that. For a moment the lights didn’t seem bright enough to him either. ‘I don’t want to know. It doesn’t matter, doesn’t make any difference.’

‘Please yourself,’ said Redbeard. He turned to look out of the window again. ‘Where am I going to sleep tonight?’ he said. ‘I’m not used to sleeping rough any more.’

Kleinzeit almost broke down and cried, he was suddenly so full of pity for Redbeard. He could see that he was afraid even to go out into the street, let alone sleep out of doors. ‘My place,’ he heard himself say. Strange that he hadn’t thought of it lately, hadn’t gone there in his excursions from the hospital. His flat. Clothes on hangers, things in drawers. Shoe polish, soap, towels. Silent radio. Things growing quietly bearded in the fridge and no one to open the door and make the light go on. Good job there were no fish in the aquarium, only a china mermaid. He heard the click of a key on the table top, saw his hand putting the key there, heard himself tell the address. ‘Drop the key through the letter box when you go,’ he said. ‘I’ve a spare one in my pocket.’

‘Thank you,’ said Redbeard.

Kleinzeit was thinking about his aquarium, the waving of the plants and the shimmer of the green sea-light on the stones when the bulb was lit, the steady hum and burble of the pump and filter system, the blank mysterious smile of the voluptuous china mermaid. He had set it up soon after getting the flat but had never got round to putting fish in it. ‘You’re welcome,’ he said, noticed that he was speaking to an empty chair. What have I done? he thought. He’ll steal everything in the place. He doesn’t know I’m at Hospital. Will he stay more than one night?

He went out into the street. It was too dark, ought to have been lighter. There’s less of everything, he thought. There’s a constant reduction going on. As he walked he looked down at steel plates of various sizes and patterns let into the pavement, quietly reflecting the blue light of the street lamps. North Thames Gas Board. Post Office Telephones. There was none that said Kleinzeit.

He went into the Underground, back to Sister’s place, proudly unlocked the door with the key she had given him, lit the gas fire, sighed with comfort. The bathroom smelled like naked Sister. When he looked in the mirror Hypotenectomy, Asymptoctomy, Strettoctomy moved in between him and his face. O God, he said.

God here, said God. Please notice that it wasn’t Shiva that answered.

I’m noticing, said Kleinzeit. Listen, what am I going to do?

About what? said God.

You know, said Kleinzeit. All this at the hospital. The operation.

Right, said God. Dichotomy, was it? I’m sorry, I seem to have forgotten your name.

Kleinzeit, said Kleinzeit. Hypotenectomy, Asymptoctomy, Strettoctomy.

My word, said God. That’ll take a lot out of you, won’t it.

Is that all you’ve got to say? said Kleinzeit.

Well, Krankheit, old chap …

Kleinzeit, said Kleinzeit.

Quite. Kleinzeit. It’s your show of course, but if I were you I’d simply not bother with it.

Not go ahead with the operation, you mean?

Precisely.

But what if I have more pains and things?

Oh, I should think you’ll have those in any case, with or without surgery. It’s a gradual falling-apart process, one way or another. Entropy and all that. Nobody lives forever, you know, not even Me. What you need is an interest. Find yourself a girlfriend.

I have done, said Kleinzeit.

That’s the ticket. Take up the glockenspiel.

I’ve done that too.

Well then, said God. There you are. Give the yellow paper a whirl. Let me know how it goes, Klemmreich, will you.

Kleinzeit, said Kleinzeit.

Of course, said God. Don’t hesitate to call if I can help in any way.

Kleinzeit looked up at the bathroom light. Must be a 10-watt bulb, I swear, he said, brushed his teeth with Sister’s toothbrush, went to bed.

In the morning Sister got into bed, shoved her cold bare bottom at him.

Right, thought Kleinzeit. I don’t care if God forgets my name.

Ponce

Kleinzeit went to the hospital, emptied his locker, packed his things.

‘Where’ve you been?’ said the day sister.

‘Out,’ said Kleinzeit.

‘Where’re you going now?’

‘Out again.’

‘When’re you coming back?’

‘Not coming back.’

‘Who said you could leave?’

‘God.’

‘Be careful how you talk,’ said the sister. ‘There’s a Mental Health Act, you know.’

‘There’s a Church of England too,’ said Kleinzeit.

‘What about Dr Pink?’ said the sister. ‘Has he said anything about discharging you? You’re scheduled for surgery, aren’t you?’

‘No, he hasn’t said anything,’ said Kleinzeit. ‘Yes, I’m scheduled.’

‘You’ll have to sign this form then,’ said the sister. ‘Discharging yourself against advice.’

Kleinzeit signed, discharged himself against advice. He said goodbye to everybody, shook hands with Schwarzgang.

‘Luck,’ said Schwarzgang.

‘Keep blipping,’ said Kleinzeit.

When he walked down the stairs his legs trembled. Hospital said nothing, hummed a tune, affected not to notice. Kleinzeit had the half-sick feeling he remembered from playing truant as a child. At school the other children were in the place where they were meant to be, safely encapsulated in their schedule, not alone like him under the eye of whatever might be looking down. The sunlight in the street was scary. Behind him Hospital preserved its silence, stretched out neither hand nor paw. Kleinzeit had nothing to hold on to but his fear.

It’s not as if everything’s all right, he said to God. It’s not as if I’ve had the operation and now my troubles are over.

And if you’d had the operation would your troubles be over? said God. Would everything be all right? Would you live forever in good health then?

You’re too permissive, said Kleinzeit. It scares me. I don’t think you care all that much about what happens to me.

Don’t expect me to be human, said God.

Kleinzeit leaned on his fear, hobbled into the black sunlight with trembling legs, found an entrance to the Underground, descended. Underground seemed the country of the dead, not enough trains, not enough people in the trains, not enough noise, too many empty spaces. Life was like a television screen with the sound turned off. His train zoomed up in perfect silence, he got in. In the empty spaces his wife and children spoke, sang, laughed without sound, the tomcat shook his fist, Folger Bashan was smothered with a pillow, his father stood with him at the edge of a grave and watched the burial of trees and grass and blue, blue sky. The train could take him to the places but not the times. Kleinzeit didn’t want to get out of the train, there was no time there, nothing had to be decided. He dropped his mind like a bucket into the well of Sister. There was a hole in the bucket, it came up empty. He still had a month’s notice to work out at the office, he remembered suddenly. A month’s pay. He’d not even rung up to say he was at hospital. A boy and girl entered the train, wrapped their arms around each other, kissed. They have no troubles, thought Kleinzeit. They’re healthy, they’re young, they’ll be alive long after I’m dead.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Kleinzeit»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Kleinzeit» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Kleinzeit» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.