Russell Hoban - Pilgermann

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Hoban - Pilgermann» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Pilgermann

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Pilgermann: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Pilgermann»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Pilgermann — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Pilgermann», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘No,’ he said, ‘I was intent on the placing of the tiles. Did you?’

‘No,’ I said, ‘I simply forgot all about it.’ ‘Our first lesson,’ said Bembel Rudzuk: ‘the heart of the mystery is meant to remain a mystery.’

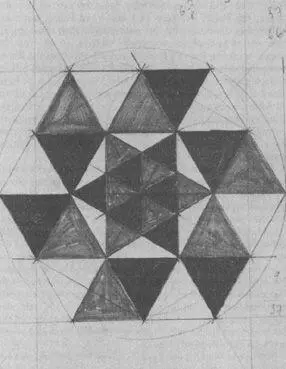

Hidden Lion! (For me that would always be the name of precedence; the Willing Virgin was the name for an aspect of the pattern that had not been made apparent to me by the pattern itself.) To see that central hexagon in its full-scale alternation of large and small red and black and tawny triangles, its solid and tangible actuality of fired and glazed tiles, was quite astonishing, there was so much action in it. I have before this described my drawing of the twelvefold repetition and my surprise at the quantity and variety of the action in it. But here there was as yet no repetition, there was only this hexagon made up of large and small triangles: the eighteen large outer ones; the twelve small inner ones; the six shallow ones between the inner and the outer. It was immediately apparent that the large interlocking red and black and tawny triangles of the outer hexagon were predisposed to turn, to revolve, to remind themselves that they were born of a circle. To this central hexagon at Bembel Rudzuk’s request I gave a name: David’s Wheel.

Firouz came to us again that day and stood looking at David’s Wheel, magnetically drawn, it seemed, by the pattern. This time he seemed to be without animosity, seemed to look on us with respect, as when a little boy watches his father string a bow that he himself will not be able to bend until he is grown a man. He spread out his fingers as if gripping a small wheel, he rotated his outspread, hooked fingers. ‘It turns,’ he said, ‘there is a turning in it: the turning of the sun and the moon and the stars; the turning of the wheels of fate and fortune. Thus do we see that at the centre of the universe there is a turning, there is a turning at the heart of the mystery. This turning pattern that you have made with these tiles, has it a name?’

‘David’s Wheel,’ I said, and then I was sorry that I had said it; I didn’t want him to know the name of anything that meant anything to me.

‘David’s Wheel,’ he said. ‘David slew Goliath and became a great king. And yet he turned, did he not. He turned from what was right, he turned to the wrong, he lusted after Bathsheba, he told Joab to put Uriah her husband in the forefront of the hottest battle. Then when Uriah was dead he joyed himself, did he not, with Bathsheba the juicy widow, the fruit of his wrongdoing.’

‘He was only a man,’ I said. ‘He made music, he sang and danced before the Lord.’

‘Only a man!’ said Firouz. ‘Only a man!’ He turned on his heel, always he left with that heel-turn, never did he simply walk away as others did.

Tower Gate now made his appearance, drawing near in a manner that commanded attention by the power of his attention; he came as if mystically summoned by David’s Wheel, and he so focused his approaching presence on that hexagon that it seemed to be a winch that was winding him in with an invisible rope.

When he arrived at David’s Wheel he looked down into it with a look that made me feel utterly left out and excluded from any understanding whatever of the thing that I had summoned with my compass and my straight-edge; one sees that always with specialists: a bowman picks up a bow in a way that leaves the non-bowman feeling poor; a silk merchant reads the silk with his fingers and almost there rise up from his touch phantom ships and camels, distant mountains, distant seas. Tower Gate looked down into David’s Wheel and in his face I tried without success to read whether he looked into crystalline depths or into an abyss of smoke and flame.

‘What do you see?’ I blurted out.

He looked at me as if I had farted during prayers, looked away graciously, then looked back with a face that showed willingness to put the incident behind us. ‘Let me show you the plan and elevations for the tower,’ he said to Bembel Rudzuk, and opened a roll of drawings which he handed to his foreman, who laid them on David’s Wheel and put loose tiles on the corners to hold them flat.

‘This tower wants to be very plain,’ said Tower Gate; ‘it wants to be nothing immodest, nothing too commanding. It is a little hexagonal tower with its stairs going round the outside of it. This is not a seashell that grows itself round its own spiral and remembers in its windings the sound of the sea; this tower remembers nothing and its unsheltered spiral is open to the sky.

‘To what is the height of this tower related? To the triangles on which it stands. These triangles offer us an angle of thirty degrees, an angle of sixty degrees, and an angle of one hundred and twenty degrees. The obtuse angle not being usable we try the other two: projecting a sixty-degree angle from the edge of your square to a point above the centre gives us a tower more than a hundred feet high, a real God-challenger and not to be thought of even if it were practically possible on a base only six feet four inches across; projecting a thirty-degree angle gives us a tower about thirty-five feet high which is still a little pretentious. What then remains to us? In reverence and in modesty (if indeed we can apply such words to a project so thoroughly dubious) we halve that angle and arrive at this tower just over sixteen feet high, taller than a man on a camel but not so high in the air as the mu’addhin; it is a height for broadening one’s view a little but not for feeling too far above the world.’

‘I am powerfully impressed by the care you have taken in this matter,’ said Bembel Rudzuk, ‘and I am profoundly grateful for the discretion you have shown; one can so easily do the wrong thing.’

‘We may well have done the wrong thing in any case,’ said Tower Gate, ‘but life is after all a matter of making choices and one is bound to choose wrong in one or two of those matters that really matter.’

So the tower was built. It had no ornamentation, no red and black triangles; it was made of plain tawny bricks. The platform at the top was built out a foot wider all round than the base; it was enclosed by a parapet three feet high and left open to the sky.

The tower being complete the pattern began to spread outward from it. I felt a pang of regret: once begun, a project can only be completed or abandoned; actuality is gained as potentiality is lost. There was no stopping the growth of Hidden Lion; the serpents twisted through the stars, the pyramids shifted and regrouped, the lions appeared and disappeared, the illusory enclaves of disorder were suddenly there, suddenly not there. And under each tile a name of God.

To visualize a pattern, whether in a drawing or in tiles or even to see it with the eye of the mind only, is to make visible the power in the pattern. Because of the scale of Hidden Lion the power was very clearly to be seen from the top of the tower; it was like the power that surges beneath the skin of a strong river.

‘This motion that we see is the motion of the Unseen,’ said Bembel Rudzuk. ‘This power that we see is the power of the Unseen, and it is both conscious power and the power of consciousness. Here already are two of my questions answered: motion is in the pattern from the very beginning because the motion is there before the pattern, the pattern is only a mode of appearance assumed by the motion; consciousness also is in the pattern from the very beginning because the consciousness is there before the pattern, the pattern is only a kind of window for the consciousness to look out of. Although serpents, pyramids, and lions seem to appear in the pattern, that is only because the human mind will make images out of anything; the pattern is in actuality abstract, it represents nothing and asserts no images. It offers itself modestly and reverently to the Unseen and the Unseen takes pleasure in it.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Pilgermann»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Pilgermann» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Pilgermann» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.