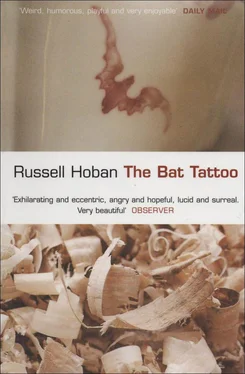

Russell Hoban - The Bat Tattoo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Hoban - The Bat Tattoo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Bat Tattoo

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Bat Tattoo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Bat Tattoo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Bat Tattoo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Bat Tattoo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I never said you were inadequate. Don’t be angry, stay and have coffee with me.’

‘Thanks, but I don’t feel up to it.’ He turned to go.

‘Wait!’ I said. ‘The hand!’ I held it out to him.

‘I don’t want it,’ he said with something like a snarl.

‘Maybe it wants you.’

‘No.’

‘Please, it doesn’t belong with me and I don’t want to sell it or give it to anyone else. Maybe you don’t want it but I need to give it to you. Please?’

He bared his teeth, shook his head, took the hand, put it in his pocket, and walked away as Violetta expired in the Apple Market.

17 Adelbert Delarue

Always I underestimate the effect on me of what I do. Did I think I could go to Autun and come back the same as I was before? On my return I looked at everything with eyes on which were imprinted scenes of this time alone and the first time with Solange. And in my ears was still the shouting of the bells.

Victoria tried to interest me in our usual games. She brought out the toys and demonstrated that in my absence new partnerships had been established. By now all four figures had names: the man was Max, the woman Celeste, the mastiff Hector and the gorilla Marcel. Marcel and Max were now an item, while Celeste and Hector had formed a serious attachment, particularly piquant when they performed to the accompaniment of that part of Swan Lake where the corps of pretty swanettes come tripping in on point. This failed to enliven me, nor did those special attentions Victoria pressed upon me. I was haunted by the Christ on the tympanum of the west portal of St Lazare.

This outspread, open, entranced Christ, I realised, does not judge: his existence , as man and as idea, is a judgement. We pass beneath his hands to the safe sheepfold of God or we fall to the fires of Hell. The Last Judgement is every moment: even this very moment in which Celeste and Hector couple to Tchaikovsky’s ballet music and Victoria mouths her devotion. The fires of Hell are not necessarily flames tended by working-class devils with pokers and pitchforks; these fires can equally be the grey and chilly dawn in which one awakes utterly alone beside one’s lover.

I think about Roswell Clark and wonder what I expect from him. In the beginning it was clear enough: I was the patron; he was the artist whom I commissioned to make little sexually active crash-dummies: man; woman; mastiff; and gorilla. What is in my mind when I watch these various wooden couplings? What do I think of while Victoria does her best to anticipate my every desire? Sometimes I see mass graves.

Crash Test was a metaphor absurd and profound; I recognised in Clark a talent capable of surprises, possibly of development. Because of the manner in which Crash Test had drawn me to itself it seemed to me that there might be a significance, as yet unknown, in our transactions. I tend to see omens and portents in all kinds of things: if the yolk of my soft-boiled egg is at the top I expect the day to go well.

What does crashing into a wall and flying into pieces signify for me? Mortality, yes — life crashing into death; I have already spoken of that in these pages. Is there more? Is there in me a desire to crash, to go Peng! and fly into pieces? Have I already flown into pieces without the Peng? What did I think my toys would do for me? From depravity does one move on to something higher? Depravity, I think, comes naturally to the human animal. And it is of course more fun than higher things.

As I was saying, in the beginning I was the patron. As I commissioned the man and woman, the mastiff, and the gorilla, I felt each time that Clark and I were moving closer to something of importance, something that would come from him as his talent demanded more of him. What will it be? The large and the small of it is that I am depending on Roswell Clark for something, I know not what, that will make me feel better than I do now. Money can buy many things, and uncertainty is one of them.

18 Roswell Clark

I had another Jennifer dream. We were on a train, just the two of us. It was the 13.24 to I don’t know where. I tried to read our destination on my ticket but the letters wouldn’t form a name. I couldn’t read the names of the stations we passed through either. There was no one else in our carriage; the lighting was dim and kept flickering; there was rubbish on the tables and all over the floor, empty beer and soft-drink cans rolling about. We were both hungry and we’d expected to get something on the train but there was no announcement about a buffet car. When the conductor came through to punch our tickets I asked him, ‘Where are we going?’

He pointed to my ticket and said, ‘There.’ He looked like the manual-training teacher I’d had in junior high school: large freckled hands with part of his right index finger missing.

‘Where’s the buffet car?’ said Jennifer.

‘This train doesn’t exist,’ he said. ‘It’s a dream train so there’s no buffet car on it.’

‘Then how come there’s buffet-car rubbish all over the place?’ said Jennifer. ‘People have been eating and drinking buffet-car food and drink here.’

‘Not my problem,’ said the conductor. ‘Talk to the Transport Minister.’

‘If at least there were bar service!’ said Jennifer as I woke up. I was hungry and I felt sad because Jennifer had been hungry too and wanted a drink but there was nothing she could do about it because there wasn’t a Jennifer any more. Her hunger and her thirst, all of her wants are gone and the world goes on without her except when in the loneliness of death she visits me in a dream.

I had two fried eggs and bacon and toast and jam for breakfast. After my coffee I had a Glenfiddich for Jennifer. Then I had one for me because I was alive and could do that. ‘Here’s looking at you,’ I said to both of us. ‘I know I haven’t been doing much lately but I’m not idle; I’ve been making sketches.’ Which was true. I didn’t want to say anything more about it, even to myself. If there was really anything happening, I’d be the first to know.

My chisels and gouges hung in their pockets, sharp and ready to bite into wood or turn in my hand and plunge into my flesh. ‘I know it’s hard for you to hang about like this,’ I told them, ‘but maybe there’ll be work for you soon.’ I looked around at the workbench, the drawing table, the easel. I didn’t want to stay in the house; it was raining and I felt like walking in it.

I put on an anorak and my rain hat, then went to the jacket I’d last worn and got my house keys out of the right-hand pocket. I checked the left-hand pocket without remembering what was in it, then drew back suddenly as my fingers touched the crucified wooden hand Sarah Varley had given me. ‘Oh, yes,’ I said. ‘Thank you very much — it’s just what I’ve always wanted.’ I put it on the drawing table, then picked it up again and put it in my anorak pocket.

Then it was like a cut from one scene to another in a film: I was in the North End Road standing by the railings of St John’s. It was a real November rain by now, wind spattering the yellow leaves that lay everywhere like fallen hours, days, years. Jesus on his cross was wet and gleaming. Suddenly I felt sorry for my smartass remarks about his fibreglass slickness; he was only a humble artefact, one of millions of images, some of them great and some of them not, reiterating the idea of this one who was called the son of God, crucified large and small, indoors and out, in marble, bronze, wood, and plastic, in wayside shrines and echoing cathedrals and little hand-held crosses, dying twenty-four hours a day for our sins.

The low-budget drinking community was not in its usual place but I had the feeling that Abraham Selby was going to turn up and after a while he did. This time he had an umbrella instead of a can of John Smith.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Bat Tattoo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Bat Tattoo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Bat Tattoo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.