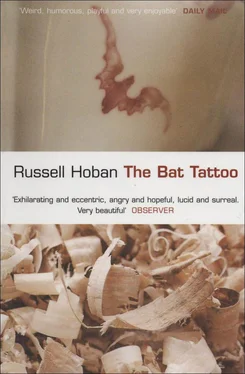

Russell Hoban - The Bat Tattoo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Russell Hoban - The Bat Tattoo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2004, Издательство: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Bat Tattoo

- Автор:

- Издательство:Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

- Жанр:

- Год:2004

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Bat Tattoo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Bat Tattoo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Bat Tattoo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Bat Tattoo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘I’ve got a Butler & Wilson French-poodle brooch here but no Scotties.’

‘I mean a live dog, the kind you take for walks.’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘My two are so clever — when they see me getting ready to go out they run and get their leads and wait for me by the door. They love to get into bed with me when I watch television. They especially like those old Lassie movies. Children might disappoint but dogs never.’

‘Do you have any children?’ I was trying to see around her for prospective customers but I wasn’t having much luck.

‘No,’ she said, and at this point Roswell appeared with the coffee and tea and gently and apologetically overlapped into the space she was occupying so that she was eased out of it. ‘Don’t forget,’ she said as she removed herself, ‘I’m always in the market for Scotties!’

As we drank our coffee and tea there appeared one of my regulars, a pleasant and enthusiastic woman from New York who likes to spend money on costume jewellery. Florence, her name is, but I always think of her as Floradora because of her flamboyance. She’s a small woman but dresses as if she were a large one, favouring large prints in bold colours and jewellery that can be seen clearly from a distance. Today her frock featured red cherries as big as oranges on a black background. She wore her grey hair in a beehive, with red-framed spectacles, red plastic hoops in her ears, and a necklace of shiny plastic cherries and green leaves. Florence is secure with her style; she knows what she likes, has fun looking for it, and enjoys being herself. I like her for that. Plus she puts her money where her taste is.

‘What’ve you got for me?’ she said. ‘I haven’t bought anything yet this trip, I’ve been saving myself for you.’

I took out the Schiaparelli necklace and earrings I’d been keeping under wraps with her in mind. Purply and iridescent, shimmery and splendid, they would have looked good on a six-foot showgirl. ‘What do you think?’ I said.

‘Mmmm!’ said Florence. ‘You know me too well. I surrender. Will I leave here with enough money to get back to the hotel?’

‘You’re a regular,’ I said, ‘and I’ll give you a friend’s price which is a little better than I’d give a dealer.’

‘I appreciate that. How much?’

‘Three hundred.’

She blew out a little breath and nodded. ‘Worth every penny too; there’s not enough sparkle in the world.’ She counted out six fifties, I wrapped the necklace and earrings in tissue paper, put them in a small Harrods bag, and we shook hands. ‘Now I’ll need a new dress,’ she said. ‘A woman’s shopping is never done.’

‘Life is hard. Be brave. Come back soon.’ We were all smiling after Florence left. The money made this a good day but my main satisfaction came from having judged correctly that she’d go for the Schiaparelli. The buskers in the Apple Market had finished with Carmen some time ago and were waltzing with Johann Strauss, Tales from the Vienna Woods . All the aisles between tables were full of people by now, eyes hard with acquisitiveness, their mouths busy with buns and coffee, the money in their wallets and purses eager to jump into ours. The lilt of the music lifted the sounds and smells of the market, the voices and the footsteps and the pigeons plodding on the cobbles, and I hummed along with it.

Roswell had picked up a little Goebel china figure from my table, probably from the fifties, a model of a nutcracker, one of those toothy chaps with tremendous jaws worked by a lever in the back. He was four inches high with a bushy white beard, wearing the uniform of Frederick the Great’s tall troopers: blue shako with a red plume, short red frogged jacket, white trousers with a blue stripe, shiny black boots. He was holding his sword upright against his shoulder and grinning heroically with his many teeth. He wasn’t a working model, couldn’t crack nuts, and if enlarged to full human scale would be very short and stubby; but he seemed cheerfully capable of crunching any difficulty whatever. Not a failer.

Roswell was grinning back at the little china man. ‘This one talks to me,’ he said. It was priced at twenty and he reached for his wallet.

‘Put away your money,’ I said. ‘You caught a thief, saved a ring, and brought me luck. Have it as a little thank-you from me.’

‘He’s a short guy but that’s a big thank-you,’ said Roswell. ‘Thank you .’ He seemed about to say more, blushed, decided not to, looked at his watch, said, ‘I haven’t done any work yet today. See you.’ And left. Whistling ‘Is That All There Is?’.

Alison and Linda were looking at me in a smirking sort of way.

‘What?’ I said.

‘A famous madam,’ said Linda, ‘once said that when you start coming with the customers it’s time to leave the business.’

‘I’m not all that professional,’ I said, ‘and I’m feeling expansive. This is one of the good days.’

8 Adelbert Delarue

Strongly intriguing, is it not, the variety of ways in which we humans replicate ourselves? I do not speak of the process of reproduction here, no. I have in mind dolls, models, puppets, toys soft and hard, with clockwork and without. I have a little tin clockwork porter who pushes a tin trolley piled high with tin luggage. I have a smiling plastic gymnast who does marvellous things on the bar and never tires as long as his clockwork is rewound. I have a tin ice vendor who pedals his icebox tricycle but has no tin customers. These little toy people do the same as their human counterparts but they do not relieve the humans of their duties.

I think now of crash-dummies, little ones first. The wooden two who make love to the sound of a crash, their black-and-yellow discs emphasise the motion of their bodies. So erotic is the sight of them as with blank blind faces they couple without fatigue and inspire Victoria and me to new heights of passion. Why should the action of these dummies have that effect? I think it is because always more sexual excitation is needed, and to see the toy copulating while we do the same is exciting. And there move with us the black-and-yellow discs we have painted on ourselves. Other elements come into it; there was a film called Crash in which the Eros/Thanatos theme was explored with many crashes and sexual acts. It goes without saying that the meeting of hard metal and soft flesh is provocative, and to be naked in a car is already an acceptance of whatever may follow. But this is not what is now uppermost in my mind.

Car crashes arise from drunkenness and careless driving, excessive speed and sleeping at the wheel. These are sins for which many die each year. In the hope of avoiding death we strap dummies into cars and make them die for us. From these harmless deaths we gather data so that we may crash without dying.

Sometimes in the small hours of the night Victoria and I paint our bodies with black-and-yellow discs and our nakedness we cover with black silk dressing-gowns. Then I ring for my chauffeur Jean-Louis and he knows that I want the black Rolls-Royce with the black windows. In the car, quick, quick, we are again naked. Under us the leather upholstery is cool in summer, warm in winter. The Rolls-Royce hums smoothly through the quiet streets, then on to the Périphérique where it acquires speed. On either side rush past the darkness and the lights of Paris and as we fasten ourselves to each other I feel the black-and-yellow discs moving with us and I imagine the impact, the noise and the pain of a high-speed crash. Strange, is it not, what games the mind will play? The crash that impends always, the sudden violent death are built into this road and this motorcar that wants always to go faster. The death in the road and in the machine, the velocity of the car and the feel and smell of the upholstery excite us, cradle us as we give ourselves to each other and the night. We make love, then sleep and love again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Bat Tattoo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Bat Tattoo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Bat Tattoo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.