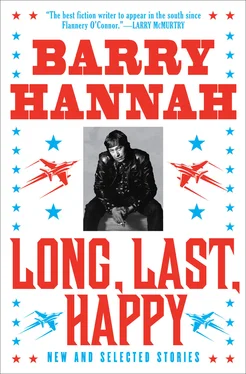

Barry Hannah - Long, Last, Happy - New and Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Barry Hannah - Long, Last, Happy - New and Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Ross, through life, had experienced unsafe moments. He knew where Newt’s melancholy came from. It was not being sued by that true hack whose biography Ross had done. It wasn’t Ross’s fault the man was too lazy to read the book before it came out, anyway, though Ross had rather surprised himself by his own honesty, bursting out here at age fifty-two — why? Nor was it the matter of the air rifle that always rode close to him. Nor was it a panic of age and certain realizations, for instance that he was not a good lover even when he loved his wife, Nabby. He knew what was correct, that wives liked long tenderness and caressing. But he was apt to drive himself over her, and afterward he could not help despising her as he piled into sleep for escape. She deserved better. Maybe his homicidal thoughts about her were a part of the whole long-running thing. The flashes of his murderous thoughts when she paused too long getting ready to go out, when she was rude to slow or mistaken service personnel, when she threw out something perfectly fine in the trash, just because she was tired of it or was having some fit of tidiness; even more, when she wanted to talk about them, their “relationship,” their love. She wondered why they were married and worse, she spoke this aloud, bombing the ease of the day, exploding his work, pitching him into a rage of choice over weapons (Ross chose the wire, the garrote, yes!). Didn’t she know that millions thought this and could shut up about it? Why study it if you weren’t going to do anything? She did not have the courage to walk out the door. He did, though, along with the near ability to exterminate her. She also called his work “our work” and saw herself as the woman behind the man, etc., merely out of cherished dumb truism. But none of these things, and maybe not even melancholy, could be classified as the true unsafe moments.

Especially since his forties, some old scene he’d visited, made his compromises with, even dwelled with, appeared ineffably sad. Something beyond futility or hopelessness. It was an enormous more-than-melancholy that something had ever existed at all, that it kept taking the trouble to have day and eyesight on it. He felt that one of them — he or it — must act to destroy. He would look at an aged quarter — piece of change — and think this. Or he would look at an oft-seen woman the same way. One of them, he reasoned, should perish. He didn’t know whether this was only mortality, the sheer weariness of repetition working him down, calling to him, or whether it was insanity. The quarter would do nothing but keep making its rounds as it had since it was minted, it would not change, would always be just the quarter. The woman, after the billions of women before her, still prevailed on the eyesight, still clutched her space, still sought relief from her pain, still stuffed her hunger. He himself woke up each morning as if required. The quarter flatly demands use. The woman shakes out her neurons and puts her feet on the floor. His clients insisted their stories be told. He was never out of work. Yet he would stare at them in the unsafe moments and want the two of them to hurl together and wrestle and explode. His very work. Maybe that was why he’d queered that last bio. The unsafe moments were winning.

Ross’s Buick Riviera, black with spoked wheel covers, was much like the transport of a cinematic contract killer; or of a pimp; or of a black slumlord. There was something mean, heartless and smug in the car. In it he could feel what he was, his life. Writing up someone else’s life was rather like killing them; rather like selling them; rather like renting something exorbitant to them. It was a car of secrets, a car of nearly garish bad taste (white leather upholstery), a car of penetrating swank; a car owned by somebody who might have struck somebody else once or twice in a bar or at a country club. It was such a car in which a man who would dye his gray hair might sit, though Ross didn’t do this.

He kept himself going with quinine and Kool cigarettes. All his life he had been sleepy. There was nothing natural about barely anything he did or had ever done. At home with his wife he was restless. In his writing room on the pier he was angry and impatient as often as he was lulled by the brown tide. Sleeping, he dreamed nightmares constantly. He would awaken, relieved greatly, but within minutes he was despising the fact that his eyes were open and the day was proceeding. It was necessary to give himself several knocks for consciousness. His natural mood was refractory. He’d not had many other women, mainly for this reason and for the reason that an affair made him feel morbidly common, even when the woman displayed attraction much past that of his wife, who was in her late forties and going to crepey skin, bless her.

It could be that his profession was more dangerous than he’d thought. Now he could arrange his notes and tapes and, well, dispense with somebody’s entire lifetime in a matter of two months’ real work. His mind outlined them, they were his, and he wrote them out with hardly any trouble at all. The dangerous fact, one of them, was that the books were more interesting than they were. There was always a great lie in supposing any life was significant at all, really. And one anointed that lie with a further arrangement into prevarication — that the life had a form and a point. E. Dan Ross feared that knowing so many biographies, originating them, had doomed his capacity to love. All he had left was comprehension. He might have become that sad monster of the eighties.

Certainly he had feelings, he was no cold fish. But many prolific authors he’d met were, undeniably. They were not great humanists, neither were they caretakers of the soul. Some were simply addicted to writing, victims of inner logorrhea. A logorrheic was a painful thing to watch: they simply could not stop observing, never seeing much, really. They had no lives at all. In a special way they were rude and dumb, and misused life awfully. This was pointed out by a friend who played golf with him and a famous, almost indecently prolific, author. The author was no good at golf, confident but awkward, and bent down in a retarded way at the ball. His friend had told Ross when the author was away from them: “He’s not even here, the bastard. Really, he has no imagination and no intelligence much. This golf game, or something about this afternoon, I’ll give you five to one it appears straightaway in one of his stories or books.” His friend was right. They both saw it published: a certain old man who played in kilts, detailed by the author. That old man in kilts was the only thing he’d gotten from the game. Then the case of the tiny emaciated female writer, with always a queer smell on her — mop water, runaway mildew? — who did everything out of the house quickly, nipping at “reality” like a bird on a window ledge. She’d see an auto race or a boxing match and flee instantly back to her quarters to write it up. She was in a condition of essential echolalia was all, goofy and inept in public. Thinking these things, E. Dan Ross felt uncharitable, but feared he’d lost his love for humanity, and might be bound on becoming a zombie or twit. Something about wrapping up a life like a dead fish in newspaper; something about lives as mere lengthened death certificates, hung on cold toes at the morgue; like tossing in the first shovelful of soil on a casket, knocking on the last period. “Full stop,” said the British. Exactly.

Ross also frightened himself in the matter of his maturity. Perhaps he didn’t believe in maturity. When did it ever happen? When would he, a nondrinker, ever get fully sober? Were others greatly soberer and more “grown” than he? He kept an air rifle in his car, very secretly, hardly ever using it. But here and then he could not help himself. He would find himself in a delicious advantage, usually in city traffic, at night, and shoot some innocent person in the leg or buttocks; once, a policeman in the head. Everett Dan Ross was fiftytwo years old and he knew sixty would make no difference. He would still love this and have to do it. The idea of striking someone innocent, with impunity, unprovoked, was the delicious thing — the compelling drug. He adored looking straight ahead through the windshield while in his periphery a person howled, baffled and outraged, feet away from him on the sidewalk or in an intersection, coming smugly out of a bank just seconds earlier, looking all tidy and made as people do after arranging money. His air rifle — a Daisy of the old school with a wooden stock and a leather thong off its breech ring — would already be put away, snapped into a secret compartment he had made in the car door which even his wife knew nothing about. Everett Dan Ross knew that he was likely headed for jail or criminal embarrassment, but he could not help it. Every new town beckoned him and he was lifted even higher than by the quinine in preparation. It was ecstasy. He was helpless. The further curious thing was that there was no hate in this, either, and no specific spite. The anonymity of the act threw him into a pleasure field, bigger than that of sexual completion, as if his brain itself were pinched to climax. There would follow, inevitably, shame and horror. Why was he not — he questioned himself — setting up the vain clients of his biographies, his fake autobiographies, some of whom he truly detested? Instead of these innocents? They could be saints, it did not matter. He had to witness, and exactly in that aloof peripheral way, the indignity of nameless pedestrians. He favored no creed, no generation, no style, no race. But he would not shoot an animal, never. That act seemed intolerably cruel to him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.