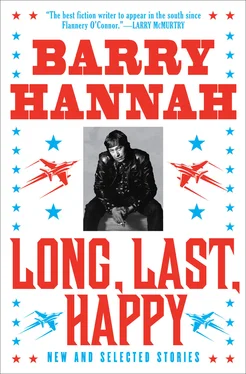

Barry Hannah - Long, Last, Happy - New and Collected Stories

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Barry Hannah - Long, Last, Happy - New and Collected Stories» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Plus all the other strange hours I felt like the robber queen. I called in sick to the lumberyard. Hoover picked me up at eight. He and his papa didn’t start off the day till ten.

She lay cold in the hall of the old house. She waved her ring finger at the whirlpool. Stop. Blood, she thought, fell out of her mind into her lungs. If she could just shape her mind with a timid effort requiring no breath, she could beckon the scroll, easing it down in millimeters. Flies had found her. She fought them, thinking.

That malt cereal that the old man ate every morning, it got on his cuffs and his newspapers from Dublin, and he wore his napkin like a bib, tucked under his neck, which glucked with the tea and cereal. His yellow cheeks and red beard, they should’ve sent him home to shave at one o’clock, but he was not American yet; more like a Mongolian with his thin eye slits; then his brogue so thick you imagined he carried heavy cereal always in his throat, had to choke back a slug of it to talk. He did not care and tinkled loudly with the door of the bathroom open while he talked to Hoover and me about religions, the mediocre number of them. It shocked him. There were only a hundred-odd Catholics in all Jackson then, 1916. Hoover courted me on the settee. I waited for the old man to flush, but he never did. I thought about that yellow water still lying there and saw green Ireland floating in it. The hairy lawn of the house, and Hoover’s body odor, and the whole milky stink of the house, they cut on me very sharp. And Hoover’s breath was of some iron pipeline.

I was happy, sucked right into the church, because I got its feeling. In St. Thomas’s it was clean, dark, cooling and beautiful, with wood rafters of cedar, gloomy green pictures of Jesus, St. Thomas and the Jordan River in glass. Also, it was tiny and humiliating. It was a thrill to cover your head with a scarf because you were such a low unclean sex, going back to Eve, I guess, making man slaver in lust for you and not be the steward he was meant to be. You were so deadly, you might loop in the poor man kneeling next to you with your hair. I saw Hoover bending on the velvet rail. I felt peculiarly trickful, that this foreign cluck would moo and prance for a look at my garters, that his slick hair would dry and stand up in heat for me. In St. Thomas’s I was thrown on that heap of navels, hair and rouge that makes the flesh-pile Woman, which even the monks have to trudge through waist-deep, I thought, before they finally ascend to sacredness. God told me this, and I blushed, knowing my power.

So I thought, that day when Hoover and I sat on his couch at one o’clock, thirty years old and smoking my first cigarette and drinking tea , that when he began playing sneaky-devious at my parts, with a whipped look on his face, this wasn’t Catholic or Irish from what I knew of them, and that it was more Mississippi Methodist in Brandon, Mississippi, with the retreat at Lake Pelahatchie and Grady Rankin working at me with his pitiful finger, and I told Hoover my opinion, leaving out Grady and so on. We both jumped through our eyes at each other then. We were soggy and rumpled as when you are led to things, and I let him, I did, let him do the full act, hurting on his bed beyond what God allows a woman to hurt. God pinched off all but a thimble-worth of pleasure in that act for me. I mean, as long as I had Hoover my husband. But I let out oaths of pleasure and Hoover in that silly position. . sometimes I take my mind up to the moon and see Hoover in that position, moving, with nothing under him. I laugh. The hunching doodlebug, ha ha ha! I was in this filthy house doing this, with an Irish Catholic. He said America was an experiment. He said I was safe in the oldest religion of historical mankind. On his bed I believed him: my hurt and fear turned to comfort.

Oh, but Papa Rooney wasn’t proud of his boy for getting his wings on me. The old man was really there at the door watching us. He’d become more an American. He’d come in to shave, and was here on us viewing Hoover in that silly position and me too. He called me names I’ll never forgive, and Hoover too. He cried, and threw cups on the floor, and lay down on the couch, talking about what he’d seen and on and on. I was numb awhile, but then I started moving, low-pedaling around the house, while Hoover sat on the bed looking at his bare feet. I found the broom and swept up the teacups and then swept the rug right beside Papa Rooney, put all the dirty lost glassware in the sink, filled it with hot water. I mopped the tiles in the kitchen and flew into the bathroom at the bowl and sink. I scraped them all with only a towel and water, then found the soap and started using that everywhere. I went back in the halls, I fingered the dust out of the space heater. I found a bowl of cereal under the bed with socks and collars lying in it. I made the old man’s room spanking clean. I made a pile for his stained underwear in the back closet. Then it was four o’clock in the afternoon. I sat down by Papa Rooney, who was still on the couch. He looked tearfully at me. “Annie, my boibee!” he said, and smothered me into his arms, asking forgiveness for what he had said. We went and sat by Hoover, while the old fellow told us about our marriage. I was scared. There seemed no other way, with Papa Rooney and his arms over our shoulders.

Except for Papa Rooney watching us all the way up the aisle, I doubt we would’ve married; we did. Through the ceremony we were both scared of — with Father Remus talking words of comfort over our heads to Mother and Daddy, who hung back and were shocked — we tied the knot.

Mother Rooney’s head stood wide open in the twirl of remembrance. Blood, eye juice and brain fluid roared down to her lungs, she thought. Too hard, too hard, her thoughts. There were noises in the house as the wind blew on the windows, which were loose in their putty. The hallway was dark. It was her box. No light now; her coffin space.

Mother Rooney shrieked, “Be loud on the organ! Pull my old corpse by a team of dogs with a rope to my toe down Capitol Street, and let Governor White peep out of his mansion and tell them to drag that old sourpuss Annie to the Pearl River Swamp. Oh, be heavy on the organ!” She shocked herself, and she remembered that Papa Rooney had died insane too, thinking that Jackson was Dublin.

The hell with the scroll! “Everything!” she howled.

The old man went crazy in a geographic way at the last, at St. Dominic’s Hospital. He shouted out the names of Dublin and Chicago and Jackson streets as if he was recalling one town he knew well. He injured his son Hoover, behaving this way. Hoover became lost; he saw the blind eyes of his daddy and heard the names of the streets. His daddy didn’t know where they were. But Annie also recalled the sane old fellow at his last, how he’d fallen in love with her; loved her cleanliness and order; loved America, because he was getting rich easily and enlarged the sewage-parts house so that now Hoover was a plumbing contractor too. Papa Rooney told her he was in love with peace and money and her — Annie.

Annie made Hoover build her a house, a house that would really be a place, so Hoover would know where he was. He seemed to, when the house was up. There was actually no reason for Hoover to go insane, because, unlike his father, he loved the aspects of his job. He loved clear water running through a clot-free pipe. He loved the wonder of nastiness rinsed and heaved forever out of sight; he loved the dribbling water replacing it in the bowl, loved the fact that water ran hot and cold; he loved thermostats. He adored digging down to a pipe, breaking it and dragging the mineral crud and roots from it, and watching the water flush through, spangling. He got high and witty watching that one day at twilight, and the slogan came to him, like a smash to Hoover’s mind: “The Plumber’s Friend.” That was how he advertised his firm in the Clarion Ledger for twenty years.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

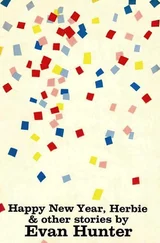

Похожие книги на «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Long, Last, Happy: New and Collected Stories» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.