They made a date for the next afternoon.

When Sjoerd came home at around eleven and went into the living room, Armanda stayed sitting close to him on the sofa and stared at the tips of her shoes with a tragic expression.

“What is it?”

He had called her that morning from Zeeland to say that that was where he was, and told her in good faith that he didn’t know yet when he’d be setting off back to Amsterdam.

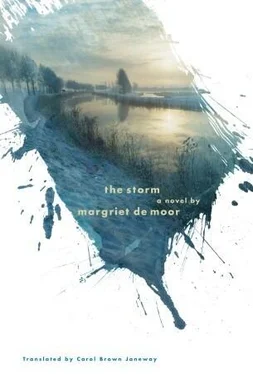

So now this situation. Remorsefully Sjoerd sank down halfway onto the floor in front of her and looked into her face. Armanda, a little encouraged by this, immediately let loose a torrent of words, she’d spent the entire day imagining the whole area he’d felt compelled to go visit all of a sudden, just like that, the map, the layout of Schouwen-Duiveland closed in by its two sea arms.

“Her map,” she sobbed openly. “Forbidden territory for me!”

Sjoerd had put his arms around her hips and her bottom. Now he slid onto the sofa next to her, pressed his face into her neck, and whispered, “No, no, you’re crazy” so compliantly into her ear that she sat up, looked around her, all animated, and exclaimed, “And what do you say to this!”

Disconcerted but still remorseful, he followed her eyes.

“What’s all this except her new house, her seven rooms, her attic, her garden to the southeast, her shed, don’t pull such a dumb face, with brand-new furniture that’s all the stuff she chose?”

She turned to him. The brief, hostile look she gave him said: Give it a minute before we make peace. “Oh you haven’t a clue how often I’ve thought, This is her life that I … okay, this is all I’m going to say: these are her chocolate caramel bars I’m eating right now, I used only to like the plain ones, her extra pounds I’m trying to lose — she got slim again so damn quickly after Nadja was born — they’re her brochures for the latest vacuum cleaners I’m looking at, and when I choose one, it’ll be the one that’ll make the least noise in her tender little ears. Do you understand what I’m talking about? This is the sixties now, the Netherlands are becoming supermodern. Do you know what I sometimes still think? Lidy’s just gone for a day, and she’s relying on me to live her life for her, all organized and proper, and that’s exactly what I’m damn well doing.”

Sjoerd listened, surrendering to her because of what he was going to do the next day. He was about to interrupt her by way of a general answer, with a quick “Hey, why don’t we go to bed?” when she stiffened again.

“Do you get it? No? Okay, then I’m also going to tell you that sometimes, no, often I see every single one of our most personal memories, think of our Sunday-afternoon walks to Ouderkerk, think of our birthdays, our Christmas dinners, I see all of it as a sort of contrast stain, a measuring stick, against her water drama in God knows how many acts … you’re shaking your head.”

Sjoerd pulled her head toward him. Pushed his nose against her ear. She said some more sad things, then indicated she was ready to go to bed with him.

· · ·

Dark. The intimate world of a bed with soft covers and sheets. No caresses. Or?

Well, yes. Sjoerd, unscrupulous or perhaps full of scruples, saw no reason to pass up the cornucopia of aroused hormones, warmth, and tenderness of a wife who was back in a good mood again (“Oh, what does it matter, he doesn’t understand and he never will”). Afterward, like any real man, he immediately fell asleep. Armanda spent a little while thinking about the menu for Sunday, when the family would be together for lunch again, this time here in their house, and pictured her table. Father and Mother Brouwer, Betsy and Leo with their two boys, Jacob, now twenty-two, with a very fat but very pretty girl with milk-white skin, Letitia, and her family too.

Asparagus? wondered Armanda. With plain boiled potatoes, thick slices of ham, an egg , and hollandaise sauce? And with it some bottles of Gewürztraminer. Or better, maybe a Riesling?

“Well,” she would have said, “the whole time we were sitting there that Sunday at midday, eating, you have to imagine the insane noise of the storm. The way I’m talking to you now, in my normal voice, it wasn’t possible. So remember that during everything I’m telling you about, everyone was screaming the whole time at the top of their lungs. It just stormed all through the middle of that day without letup, I’m not going to keep repeating it.”

That is what she would have said if at that moment a boat from, say, the river patrol had appeared at the attic window, which is not completely unimaginable, and she could have given an account later on of her anxious hours. There is quite a difference between recounting an adventure to an interested audience after it’s over, embellished here and there with a couple of invented details and facts that came to light only afterward, and living one’s own mortal danger, which must remain unvarnished, unimproved, and, basta!

“You’re probably thinking,” she would have said, “how could you eat in such circumstances, but we could. The table was a chest with a cover over it, there was a knife and a breadboard. The farmer’s wife had carried everything possible up the night before, including a bag with precious things like eggs, butter, brandy, and a spice cake, because she’d been intending to go after church in Dreischor to visit a woman who’d just had a baby. How did we sit together? Imagine eleven poor devils, gray faces, a floor that everyone knows is swaying. Horribly cold, of course, and very dark, even at noon. Cathrien Padmos, in the bed with her baby. Soon the Padmoses’ boy Adriaan crawled over to be with his mother and baby brother. It had begun to snow. We saw the window gradually become coated with snowflakes, which didn’t bother any of us, because nobody wanted to keep looking out anymore. What could be done? It must still be ebb tide, but the water was barely going down at all. Though enough that over the road, at Cau’s house, some iron palings were sticking up out of the water, and trapped in them was the body of Marien Cau; you could see deep holes in the side of his head.

“So Gerarda Hocke fried eggs. She fried them on both sides, after breaking the yolks, tipped them out of the pan onto slices of bread, and said, “Zesgever?” Or “Laurina!” What? No — nobody betrayed obvious signs of anxiety. Where that came from, I have no idea, but that’s how it was. Probably the cold made it impossible. If your body is already trembling with cold, it can’t tremble with anything else. I know that Cornelius Jaeger checked the water level from time to time. He opened the attic door, peered down the stairs, then came back again. We looked at him, agog.

“‘So?’

“‘Roughly one step lower.’

“Maybe because I learned nothing else about him, I remember very clearly the way he looked. As if he had no substance, no past, no future, other than his appearance that day at noon. Aside from the hump on his back, it was his face that was the most distinctive thing; he had very prominent cheekbones, one of them closer to the eye socket than the other, his irises were almost black, and then he had this little precocious moustache, the child was twelve, a year younger than you were, Jacob. A body full of errors, like a very remarkable charcoal drawing.

“Most of us had already had a few mouthfuls of cognac. Two glasses made the rounds. It goes straight to your head, and everything starts to spin, if you’re in the kind of situation we were in back then. I think we all felt we were still part of the world, but it was like being on a mountaintop — we were also a long way out on the edge. I still see Izak Hocke rolling himself a minuscule cigarette, with a little piece torn off one end of a paper. One of his eyes was swollen shut, half his face was a violet-blue, yet he radiated some sense of salvation the entire time. Now in his gesture as he took a few drags on the roll-your-own and then passed it on to his foreman, van de Velde, I saw something that was not perhaps so unfounded in these circumstances, namely a kind of calm despair: life has its own time limit, we all know that , but as long as we’re here, we’re here.

Читать дальше