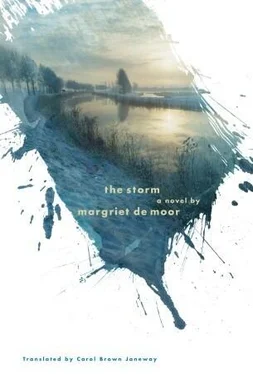

Lidy was the only one still at the window of a farmhouse that, strangely, no longer stood in the middle of fields or meadows but in an ocean current. For an inundation was no longer the word for it, what was out there on the other side of the window, the swells, was part of the sea. High tide of the North Sea with the moon in its apogee. Up in the attic of the farmhouse were now, in total, two animals and three humans. They were all absolutely still, as creatures are when they encounter something utterly unexpected that defies description. Simon Cau, a man transformed by the decision to go to a birthday party instead of checking, however quickly, on the Willems, Galge, and Westwaartse dikes, was sitting on a stool, or rather a little footstool. Because it was placed under the roof that sloped steeply down to the floor, he had had to tuck himself in, forearms on his knees, hands hanging down loosely. Gerarda Hocke was no longer making an effort to take care of him, let alone ask him to give her a hand in some fashion. In what was still the house in which she had been born and in which she intended to die, she tugged at the mattresses, held a match to the kerosene stove, adjusted the mantel, and turned off the flame again. Downstairs in the living room, tables and chairs were floating around and banging against the walls.

Lidy stood there and looked out. Very early on Sunday morning, February 1. Since waking some hours ago in a strange bed, she had never felt for a moment that she knew where she was, stuck between waking and dreaming, her memory being shuffled like playing cards between a stranger’s hands. Suddenly one of life’s most normal accompaniments, the weather, had pushed its way into the foreground in demented fashion. Was the water still rising? In her head, the wind was already blowing in longer gusts like a now familiar, deafening dream, but what about the water, which was flooding into and out of the house four or five feet below her? She thought she felt the floor sway gently under her feet. Out there, to the left along the road, was the barricade, wasn’t it, where she had had to turn around in the Citroën tonight? Impossible to tell whether any remnants of it were still poking up out of the water; the cloud cover had closed itself again to a jagged edge tinged with violet and pink, and sky and water were almost indistinguishable from each other. Yet she remained where she was, and looked. A wind from hell! she thought vaguely, lethargically. But the cows were now quiet. Through a fog of anxiety and weariness, Lidy marveled at the general destruction, as if she were an onlooker not a participant, trying to figure out how it had come about that yesterday’s trip to the seaside had got so out of hand.

Astonishing circumstances, or rather, fairly normal circumstances that had shed their skin tonight in a most astonishing fashion. These big northwesterly storms cropped up along this latitude in western Europe several times a year, after all, and spring tides were two a penny.

But tonight all this had been swept away. The visitor, snowed in here by chance, was not the only one who was bewildered. The entire delta of southwest Holland, which was always a puzzlement, was in the same predicament. Were they on one of the outlying sandbanks here that normally stayed above water off the coast of Brabant? Or were they in a real honest-to-god province, on solid ground, through which the Rhine, the Maas, and the Schelde empty themselves in an orderly fashion into the sea just as the Nile, the Seine, and the Thames do elsewhere on the planet, even when the arms of the sea reach greedily back at them along currents and channels? Not now — it would be days before the Netherlands could even believe it — but later, people would know the answer to the question of how it could possibly be that the Wester and Oosterschelde, the Grevelingen, and the Haringvliet, along with the inshore waters behind them, would flood over the islands like a plague from heaven, sweeping away 1,836 people, 120,000 animals, and 772 square miles of land at one stroke. Was this scientifically possible? Lidy stood looking until her eyes were out on stalks, her pale young face lifted above the collar of her thick coat. Scientists some years before had used a ruler to divide the North Sea that was now catapulting itself toward her into three precise sectors.

North sector, south sector, channel. Three figments of the imagination which affected Lidy tonight, like everyone else here, in the most personal way, whether she knew anything about them or not. Even the north sector, the absolutely straight line between Scandinavia and Scotland where the North Sea is still connected with the Atlantic Ocean and is also fairly deep, was something thought up by others, but frighteningly real, and that had a place in her life story. The wind had already created a modest mountain of water there hours before.

A shallow sea offers a larger spectacle: the south sector, the triangle drawn between the coasts of England, Denmark, and the Netherlands. Lidy sees a violet-tinged mountain range of water, the waves in it making peaks and valleys that cannot be underestimated, bearing down on her from all sides. Can anyone see such a thing and not be dumbfounded? And yet it is fundamentally normal, for even when there’s the lightest wind, the surface of the water begins to ruffle, the gentle push that is the beginning of every wave. But tonight the Goeree and the Noordhinder have already reported wind speeds of sixty-three knots off the coast. So: waves, enormous waves, that the eye can measure only above sea level, like icebergs, but whose main force to a fantastic degree is exercised below the surface of the water. When they encounter a shallow seabed, they get shorter but do not lose a significant amount of energy. They pile up, higher and steeper, the longer the wind blows, at the southernmost point of the south sector, where the seabed rises quickly to meet the Dutch coastline, ending at a row of dunes and an antiquated system of coastal defenses, locks, barriers, and pumping stations. Halted finally in sector three, the channel, where after more than sixteen hours of storm there’s a sort of traffic jam at the narrow bottleneck, the flood, the depth of its line of attack now stretching back more than a thousand miles, will burst unchecked into the sea arms of Zuid-Holland and Zeeland. From there it will force an exit to achieve what every liquid must achieve: its own level.

Something was coming. She pressed her forehead to the glass. To the right of the farm, something seemed to be approaching. A monster, with a light leading it. Was this Izak Hocke returning? The closer the 28-horsepower Ferguson and its trailer got, the more clearly Lidy thought she recognized him. Strange. Because the sky right now was so overcast that she could hear the water storming, but could barely see it. The slowly approaching vehicle with a man slumped down in the driver’s seat looked more like a hallucination than something out of the land of the living.

Somewhere there was a full moon, or, more accurately, it was two days after the full moon, the time when the spring tide is at its highest. But by chance tonight the moon was exercising relatively little pull; astronomically speaking, it was ebb tide. Moon and sun, aligned on the same axis, were indeed both drawing the water table upward, but the moon had just reached its farthest point on its elliptical path around the earth, the apogee, in which the forces it exerts on the tides are particularly weak. It has no relevance for the movement of light, and so this aspect of the moon’s disc during the night was fully present — cool, pale, and undiminished in its capacity from somewhere behind the cloud cover to cast its unshadowed spotlight, like the one in which Lidy now saw the tractor struggling through the water.

Читать дальше