“Yes?”

The chief engineer of the Royal Hydraulic Engineering Authorities was three-quarters asleep. The phone operator had to repeat his request twice, in different formulations. “I’m calling you in desperation, something’s got to happen.”

“Yes, well, but what can I …” the chief engineer began, then said, “Good, I’ll order the necessary measures.” He hung up again, looked at the clock, yawned, shook his head — the bright green hands were pointing to ten past four — and crawled back under the covers. But he kept his word. When he dared to rouse the queen’s commissioner from his Sunday-morning sleep with a 7 a.m. phone call, in the village under discussion the flotsam and jetsam was already thundering against the house walls and there were corpses floating everywhere.

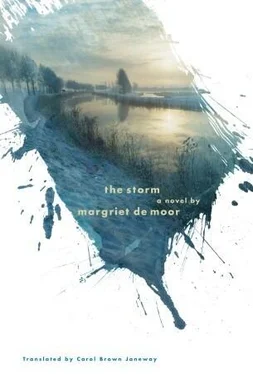

Having to die is everyman’s excusable fear, and in a region such as this, death by drowning rapidly becomes the most particular fear of all. Lidy, who had now been traveling for eighteen hours, found herself on the street with a handful of villagers who were arguing with one another. The storm had increased to force 12, i.e., a hurricane. People were wearing coats over nightclothes, and kept to the shelter of their houses; two or three of them were carrying torches. Universal darkness. Going by their faces, none of them seemed overly concerned; what was occupying each of them was what the others were making of the spectacle.

Bad weather. And not good that the water was coming over the dike out there. Everyone knew that at ebb tide that evening, the water-depth gauge at the Laurens sluice hadn’t gone down by even a quarter of an inch. And where there had been no ebb, they had projected that there would be no high tide, because this logic had held true all their lives. A young man who had been down to the harbor to take a look tonight said he’d seen the farmer at the entrance to the village hastily hitching his horses to the wagon not fifteen minutes before, with his best cows in tow, to move himself, his wife, his children, and all his worldly goods, farther inland.

The people standing around in the darkness let their eyes slide wishfully leftward, away from the silhouette of the church tower, inland, away from the sea.

Living in a dangerous place leads inevitably to a kind of deaf-and-blindness to the elements of that danger. Every single person in the street, Lidy included, knew that yes this was a village, but it was also one tiny point in a landscape given over entirely to the moon, the sea, and the wind. Water is the heaviest element in existence — that was also known. Whoever lived here was descended from generations who had centuries of experience that in long-drawn-out storms, the sea exercises a counterpressure and then rises on one side. Oceanographers had done the calculations to prove that the height of this lopsided rise is in inverse proportion to the depth of the sea — but people here had known this forever and understood it. Every person here in the street had grown up with eerie tales of monstrous hands of water reaching abruptly out of the arms of the North Sea, whose floor rises toward the coast of this country like a chute.

Lidy glanced to the side. The old woman had nudged her.

“I think I’d better carry some things upstairs.”

“I’d do the same,” replied Lidy, and thought: I’ll give the woman a hand for a few minutes.

Other people, too, were giving one another meaningful looks. The group in the street broke up. Shutters and attic windows had already been made fast that afternoon. There was nothing on any of the farms still standing around loose. Now they went to fetch their children out of bed, taking all the covers with them, and to settle them back down in attics, along with buckets of water, camping stoves, supplies, matches, and even perhaps the most valuable thing in the house, the black sewing machine with the cast-iron treadle.

Permission to stay granted, and best not to think too much. Another way of fighting back against the impossibility of nature. It is true that most of the houses in this street were little buildings put up for farmworkers, with walls thrown up using not cement but a pitiful mixture of sand and plaster. But they were their dwellings, and they wanted to feel safe in them. For the time being they wanted to have the interval between one sleep and the next preserve as much of the order of their everyday lives as possible.

Lidy went back into the little shop. The old woman walked resolutely ahead of her through the dark. Behind an intervening door the candle was still burning.

A few seconds later: “Here, you take these.”

She had two large biscuit tins pushed into her arms.

“There.”

A cash box.

Filled with the same dreamlike sense of closeness she’d experienced a few hours earlier at the family dinner, Lidy climbed a ladder to a peaked attic where she couldn’t stand upright. In the circular glow cast by a tealight she saw her feet encased in muddy shoes. A person must have two or three different people inside them, she thought, as she stood at the top of the ladder to receive a cushion, parts of a kapok mattress, a chamber pot, a coverlet, and then another.

“Got it?”

“Yes.”

She set the things on the floor, pushing aside with her foot what was lying there. The shrieking night outside and the sea, which she’d seen with her own eyes at the crest of the dike, had been shrunk again to something less enormous in this creaking, groaning little hut. As the other woman worked her way up through the trapdoor, now wearing a hairy brown coat, she looked at her crumpled old face, lit from below. Enough? Everything the way you want it? And imagined herself and the old lady, when dawn came a few hours later, carrying the whole lot back down and making coffee in the kitchen behind the shop.

“Quiet!”

The old woman turned her head toward the din raging a hand’s breadth over their heads. Then Lidy heard it too. Laboriously, at intervals, yet unmistakable, the sound of a bell was making itself heard in the wind.

So he managed it, she thought.

And immediately thereafter she felt, more than she saw, the old woman’s eyes fix themselves on her, huge and dark with anxious recognition.

“Fire!”

Simon Cau hadn’t been able to get the key to the bell tower. It was no help at all that he knew where the sexton — a good carpenter and also the commandant of the fire brigade — lived. Neither ringing the doorbell nor banging a stick against a windowpane had succeeded in waking the man, who as he slept had one ear cocked only for the sound of the telephone. After some time a blacksmith had got out of bed in a neighboring house. It wasn’t long thereafter before the hinges of the door to the church tower gave way under the blows of a sledgehammer, and Cau and the blacksmith climbed the stairs by the light of an oil lamp. At first they were barely able to coax a sound from the bell. The failed electrical mechanism gave off sparks when they tried it with a rope. So Cau had run back down and fetched the sledgehammer.

When Lidy and one of the Hin daughters wanted to attract the attention of the men a short time later, they found it hard to do. The two of them had met outside the church: Lidy sent out by the old woman to find out what was going on, and the tavernkeeper’s daughter to spread some reassuring news.

“The water’s going down again already,” the girl said.

It was no easy task to bring the good news up into the tower. Lidy and the tavernkeeper’s daughter stood in the stairwell with their fingers in their ears, looking up at the two men who were going at it as if possessed. The blacksmith, hanging onto the rope with all his weight, managed to keep the bell swinging in the correct rhythm while Simon Cau, who clearly didn’t find the heavy booming sufficient, struck the sledgehammer against the rim, which produced an additional high-pitched clang. Eventually they noticed the two young women.

Читать дальше