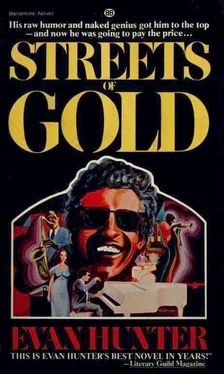

Evan Hunter - Streets of Gold

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Evan Hunter - Streets of Gold» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: New York, Год выпуска: 1975, ISBN: 1975, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Streets of Gold

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1975

- Город:New York

- ISBN:978-0-345-24631-8

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Streets of Gold: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Streets of Gold»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Streets of Gold — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Streets of Gold», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I walked the cobbled streets, the same streets he had walked as a boy, and the August sun burned hot on my bare head, and I reached down to touch the cobbles. What you walk on in the street. Here. Put your hand. Touch. Feel. Ignazio Silvio Di Palermo, four years old, squats at the First Avenue curb outside his grandfather’s tailor shop and sticks his hand down between scabby knees — which bleed when he picks them, he is told, though he cannot see the blood, and can only feel it’s warm ooze; You are bleeding, they tell him, and they tell him the color of blood is red, it is what runs through your body and keeps you alive — reaches down, his hand guided by his grandfather’s fingers around his wrist, and touches the street. And feels. Feels with the four fingers of his right hand, the fingertips gingerly gliding over the surface of the smooth, rough stones, and then circumscribing the shape of one stone, it is like a box, it is like the box he keeps the toy soldiers in, it is the shape of a box, and feeling where the next stone joins it, and the next, and forming a pattern in his mind, and his grandfather says Do you see, Ignazio? Now do you see? I walked that town from one end of it to the other, trying to pick out the locations my grandfather had described, finding the bar at which Bardoni had first broached the subject of leaving for America, sat there in the cool encroaching dusk as my grandfather must have done after a day’s work, and smelled the familiar aroma of the guinea stinkers all around me, and heard the muted hum of the male conversation, and above that, like the strident shrieks of treetop birds, the women calling to each other from windows or balconies, and the counterpoint of peddlers hawking their produce in the streets, “ Caterina, vieni qua! Pesche, bella pesche fresche, ciliegie, cocomero,” exactly as my grandfather had described it to me — or were these only the cadences and rhythms I had heard throughout all the days of my youth in East Harlem?

Brash young Bardoni had sat at a table here with my grandfather when they were still boys, boasting loudly of having fatto ’na bella chiavata in Naples, having inserted his doubtless heroically proportioned key into the lock of a Neapolitan streetwalker, while the other young men of the town, my grandfather included, listened goggle-eyed and prayed that San Maurizio, the patron saint of the town, would not be able to read their minds. In December of the year 1900, Bardoni walked my grandfather past this same café on Christmas Day, sunshine bright on cobbled streets, Bardoni dressed in natty American attire, striped shirt and celluloid collar, necktie asserted with a simple pin (Eliot’s been translated into Braille), and told him of the streets over there in America, with all that gold lying in them, and further told him that he would pay for my grandfather’s passage, and arrange to have a job and lodgings waiting for him when he got to America, and he would not have to worry about the language, there were plenty of Italians already there, they would help him with his English. All Bardoni wanted in return was a small portion of my grandfather’s weekly wages (twelve dollars and fifty cents a week! Bardoni told him) until the advances were paid off, and a smaller percentage of the wages after that until Bardoni’s modest commission had been earned, and then my grandfather would be on his own to make his fortune in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

“But I will return to Italy,” my grandfather said.

“Certo,” Bardoni said. “Of course.”

“When I have earned enough money.”

“Of course,” Bardoni said again. “ Italia è la sua patria.”

It had been a barren Christmas Day in Fiormonte. I have tried hard to understand what life in that village must have been like, because I know for certain that the life transposed to Harlem, and later to the Bronx, and later to the town of Talmadge, Connecticut (where I spent more than thirteen years with Rebecca and the children), was firmly rooted in Fiormonte. The family, the nuclear family, consisted of my grandfather, his parents, his two sisters, and his younger brother. In musical terms, they were the primary functions of the key. The secondary functions were the aunts, uncles, and cousins who lived within a stone’s throw of my grandfather’s house. The compari and comari were the godfathers and godmothers (pronounced “goombahs” and “goomahs” even by my grandfather), and they combined with the compaesani to form the tertiary functions of the key; the compaesani were countrymen, compatriots, or even simply neighbors. Fiormonte enclosed and embraced this related and near-related brood, but was itself motherless and fatherless in the year 1900, Italy having been torn bloody and squalling from the loins of a land dominated as early as thirty years before by rival kings and struggling foreign forces. Unified by Garibaldi to become a single nation, it became that only in the minds and hearts of intellectuals and revolutionaries, the southern peasants knowing only Fiormonte and Naples, where until recently the uneasy seat of power had rested. They distrusted Rome, the new capital, in fact distrusted the entire north, suspecting (correctly) that the farmlands and vineyards were being unjustly taxed in favor of stronger industrial interests. There was no true fatherland as yet, there was no sense of the village being a part of the state as, for example, Seattle, Washington, is a necessary five chord in the chart of “America, the Beautiful.” The patria that Bardoni had mentioned to my grandfather was Fiormonte and, by extension, Naples. It was this that my grandfather was leaving.

He made his decision on Christmas Day, 1900.

He had been toying with the idea since November, when Bardoni returned in splendor, sporting patent leather shoes and tawny spats, diamond cuff links at his wrists, handlebar mustache meticulously curled and waxed. The economic system in Fiormonte, as elsewhere in the south of Italy, was based on a form of medieval serfdom in which the landowner, or padrone , permitted the peasant to work the land for him, the lion’s share of the crop going to the padrone . (We call it sharecropping here.) Those carnival barkers who came back to the villages to tout the joys of living in America were padroni in their own right; a new country, a different form of economic bondage. They would indeed pay for steerage transportation to the United States, they would indeed supply (and pay for) lodgings in New York, they would indeed guarantee employment, but the tithe had to be paid, the padrone was there in the streets of Manhattan as surely as he was there in the big stone house at the top of the hill in the village of Fiormonte.

My grandfather’s name was Francesco Di Lorenzo.

The house he lived in was similar in construction, though not in size, to the one inhabited by Don Leonardo, the padrone of Fiormonte. Built of stone laboriously cleared from the vineyards, covered with mud allowed to dry and then whitewashed with a mixture of lime and water, it consisted of three rooms, the largest of which was the kitchen. A huge fireplace and hearth, the house’s only source of heat and of course the cooking center, dominated the kitchen. The other two rooms were bedrooms, one of them shared by the parents and baby brother of young Francesco — it is difficult to think of him, no less write of him, as anything but Grandpa. But Francesco he was in his youth, and indeed Francesco he remained until he had been in America for more than forty years, by which time everyone, including Grandma, called him Frank. When I was a boy, people were still calling him Francesco, though every now and then someone would call him Frank. I’m hardly the one to talk about anglicizing names, being a rat-fink turncoat deserter (Dwight Jamison, ma’am, I hope I am a big success!), but I have never been able to understand why we call Italy “Italy” and not “Italia,” or why we call Germany “Germany” rather than “Deutschland.” Who supplies the translation? Is there a central bureau in Germany that grants permission for the French people to call the fatherland “L’Allemagne”? I hate to raise problems; forgive me.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Streets of Gold»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Streets of Gold» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Streets of Gold» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.