I remember the continual to-and-fro of people getting up and carrying boxes full of books to a small table like an altar at the far end of the room. Most of them were cardboard boxes, though there were wooden boxes too, and some were even painted or varnished. Sitting behind the table was a little woman wearing a shiny blue dress and a pearl necklace, with a powdered face and white hair combed into the shape of a feathery egg. It was Sarita Subercaseaux, who later on, throughout my time there, was the high school’s headmistress. She took the boxes and examined their contents, making notes in a record book. I was following all this activity with the keenest attention. Some of the boxes were too full to be properly closed, others were half empty, with only a few books knocking around inside, making an ominous sound. Yet it wasn’t so much the quantity of books that determined the value of the boxes, though quantity did matter, as the variety of titles. The ideal box would have been one in which all the books were different; the worst (and this was the most frequent case), a box containing nothing but copies of the same book. I don’t know who explained this rule to me, maybe it was the product of my own speculations and fantasies. That would have been typical: I was always inventing stories and schemes to make sense of things I didn’t understand, and I understood almost nothing. Anyway, where else could the explanation have come from? My parents weren’t very communicative, I couldn’t read, there was no television, and the kids in my gang of neighborhood friends were as ignorant as I was.

Seen from a distance, there’s something dreamlike about this scene with the boxes of books, and the way we’re dressed up as if for a photo. But I’m sure that it happened as I’ve described it. It’s a scene that has kept coming back to me over the years, and in the end I’ve worked out a reasonable explanation. Plans must have been afoot at the time to set up the Pringles Public Library, and someone must have organized a book drive, with the support of the hotel’s proprietors: “a dinner for a book,” or something along those lines. That’s plausible, at least. And it’s true that the library was founded around that time, as I was able to confirm on my most recent visit to Pringles a few months ago. Sarita Subercaseaux, moreover, was the first Head Librarian. During my childhood and adolescence, I was one of the library’s most assiduous patrons, probably the most assiduous of all, borrowing books at a rate of one or two a day. And it was always Sarita who filled out my card. This turned out to be crucial when I began high school, since she was the headmistress. She spread the word that in spite of my tender years I was the most voracious reader in Pringles, which established my reputation as a prodigy and simplified my life enormously: I graduated with excellent grades, without having studied at all.

During my most recent visit to Pringles, hoping to confirm my memories, I asked my mother if Sarita Subercaseaux was still alive. She burst out laughing.

“She died years and years ago!” Mom said. “She died before you were born. She was already old when I was a girl. .”

“That’s impossible!” I exclaimed. “I remember her very clearly. In the library, at school. .”

“Yes, she worked at the library and the high school, but before I was married. You must be getting mixed up, remembering things I told you.”

That was all I could get out of her. I was unsettled by her certainty, especially because her memory, unlike mine, is infallible. Whenever we disagree about something that happened in the past, she invariably turns out to be right. But how could she be right about this? Perhaps I was remembering Sarita Subercaseaux’s daughter, a daughter who as well as being the spitting image of her mother had followed in her footsteps. But that was impossible. Sarita had gone to her grave unmarried and she was the archetype of the unmarried woman, the town’s classic old maid: always meticulously groomed; cool and remote, the very image of sterility. I was quite sure of that.

Getting back to the hotel. The movement between the tables in the restaurant and the little altar where the boxes were piling up was not entirely fluid. Everyone there knew everyone else — that’s how it was in Pringles — so when people got up from their tables to take their boxes to the far end of the room, they stopped at other tables on the way to greet and chat with their acquaintances. The acquaintances were careful not to talk too much, politely supposing that the people who had stopped were carrying boxes of considerable weight (even if the contents were, in fact, woefully meager). The carriers, in turn, responded more politely still by chatting on, making it clear that the pleasure of the conversation amply compensated for the effort of bearing the weight. These little transactions, informed as they were by a sincere curiosity about the lives of others, which was common to all the inhabitants of Pringles, turned out to be rich in information, and that is how we learned that the Musical Brain was being exhibited next door, in the lobby of the Spanish Theater. Otherwise, we probably wouldn’t have known, and would simply have gone home to bed. The news was an excuse to finish with the dinner, which all of us were finding tedious.

The Musical Brain had appeared in town some time earlier, and an informal association of residents had taken charge of it. The original plan had been to lend it out to private homes, for short periods, following a procedure that had been used with various miraculous images of the Virgin. Requests for those images had come from people with illnesses or family problems, while the reason for borrowing this new magical device was sheer curiosity (although perhaps there was also a touch of superstition). Since the association had no religious framework, and no authority to regulate the rotation, it was impossible to stick to a schedule. On the one hand, there were those who tried to get rid of the Brain after the first night, with the excuse that the music kept them awake; on the other hand, there were those who built elaborate niches and pedestals, and then tried to use their expenses as a pretext for prolonging the loan indefinitely. The association soon lost track of where the Brain was, and those who, like us, had never seen it came to suspect that the whole thing was a hoax. That’s why we were overcome by impatience when we found out that it was on display just next door.

Dad asked for the bill, and when it came he reached into his pocket and took out his famous wallet, for me the most fascinating object in the world. It was very large and made of green leather, marvelously embossed with complex arabesques, the back and front adorned with glass beads that composed colorful scenes. It had belonged to Pushkin, who, according to the legend, was carrying it in his pocket the day he was killed. One of my father’s uncles had been an ambassador in Russia at the beginning of the century and had bought many works of art, antiquities, and curiosities there, which his widow had distributed among her nephews and nieces after his death, since the couple had no children of their own.

The Spanish Theater, which was part of a complex belonging to the Spanish Provident Society, abutted the hotel. And yet we didn’t go straight there. We crossed the street to where the truck was parked, walked around it, and then crossed back. This detour was for my mother’s benefit: she didn’t want the diners at the hotel, in the unlikely event that they should look out of the windows and actually be able to see something, to suppose that she was going to the theater.

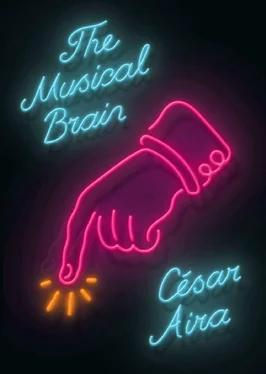

We walked into the lobby, and there it was, placed on a box, an ordinary wooden one that Cereseto (the manager of the theater) had disguised with strips of shredded white paper, the kind used for packing. The presentation was quite effective: it was like a big nest, and suggested both the fragility of eggs and that of objects packed with care. The famous Musical Brain was made of cardboard and it was the size of a trunk. It resembled a brain quite closely in shape, but not in color, because it was painted phosphorescent pink and crisscrossed with blue veins.

Читать дальше