I hadn’t heard anything about Sheikh Nureddin or Bassam since the attack, they hadn’t reappeared; little by little my fears of seeing the police turn up had lessened and the Group for the Propagation of Koranic Thought seemed far away, over there, in those endless suburbs peopled by hundreds of hicks like me, but yet very close; of course I had followed the news on TV; they ended up arresting three suspects, I didn’t know any of them: they had odd-looking faces that didn’t exude intelligence, but photos of criminals are rarely flattering. Every day I expected news of Sheikh Nureddin and Bassam being arrested, but it never came.

Just a few days after Judit left, there was another horrible attack, which profoundly affected me, as if I myself had been present, maybe because we had been at the place not long before. The Café Hafa is situated on the cliff top, suspended above the Mediterranean, lost among the bougainvillea and jasmine of the neighborhood’s luxury villas; it may well be the most famous place in Tangier and one of the most pleasant on nice days (a table set a little apart, where Judit had taken my hand before kissing me, I remember, I’ve thought about it often since, I was ashamed, very ashamed, I was afraid we’d be seen, kissing in public is a misdemeanor) especially when there aren’t many people, late morning for instance, and you feel as if you have the sea and all the Strait to yourself. I learned from the paper that a man had entered the café, taken out a long dagger or sword and attacked a group of young people sitting at a table, no doubt because there were foreigners among them; a young Moroccan my age died, and another was wounded in the thigh, a French boy; there were two Spanish girls with them: they were all students of translation at the university in Tangier. The suspect fled down the cliff, pursued by the café’s customers and waiters, and managed to escape. An artist’s rendering of his face was attached to the article; he had the same round head and childlike face as Bassam, it could have been him. Maybe he had suddenly gone mad. First Judit sees him in Marrakesh just after the explosion and then a face that resembles his appears in Le Journal de Tanger. I couldn’t picture him stabbing young students calmly sitting in the sun; it wasn’t possible that he’d changed so quickly, and yet I couldn’t help but remember how readily he had beaten up the bookseller. It seemed to me that the question Why? would remain forever without an answer, even if it was indeed Bassam who had helped place the bomb in the Café Argan and stabbed a Moroccan our age, even if I had him in front of me, if I had asked him why? why do it? he would have shrugged his shoulders; he would have answered For God, out of hatred of Christians, for Islam, for Sheikh Nureddin, what do I know, but he would lie, I knew he would lie and that he certainly didn’t know the reason for his actions which, in fact, had none, no more than there was a reason for beating up the bookseller, it was like that, it was in the air, violence was in the air, the wind was blowing that way; it was blowing pretty much everywhere and had swept Bassam up in idiocy. I thought about what I’d brought about despite myself, unhappiness and death; Bassam held the club and maybe the sword, but the ideological causes I could see from the height of my twenty years didn’t convince me: I knew Bassam, I knew that his hatred of the West or his passion for Islam were all relative, that a few months before meeting Sheikh Nureddin going to the mosque with his father annoyed him more than anything, he never bothered getting up one single time at dawn for the fajr prayer, he dreamed of going to live in Spain or France. But when I thought about it carefully I was also aware that, a contrario, just because he liked girls or dreamed of Germany and America didn’t prevent anything whatsoever. I knew that Sheikh Nureddin had grown up in France, and when I had spoken with him about it he appreciated some aspects of the country and he acknowledged that, if not for living in the midst of kuffar, infidels, it was better to live in France than in Spain or Italy, where, he said, Islam was scorned, crushed, reduced to poverty.

All those months spent with the Group for the Propagation of Koranic Thought had brought me closer to Nureddin; he was good to me and I knew (or liked to believe) that he had taken me in without any ulterior motives; he gave me lessons on morality, true, but no more than a father or a big brother. He would often repeat, laughing, that my detective novels were rotting my mind, that they were diabolical books that were driving me to perdition, but he never did anything to stop me from reading them, for example, and if I hadn’t seen him with my own eyes leading the group of fighters at night I would have been incapable of imagining for a single second that he could be connected, closely or remotely, with a violent action.

Apparently, the three brutes of the Marrakesh attack had acted alone, at least that’s what the police said; they had learned on the Internet how to create a bomb and make it explode. But Bassam’s presence there, then, affirmed by Judit, led me to envision networks, connections, paranoid conspiracies; I even thought for an instant that Sheikh Nureddin was actually in the service of the Palace, an agitator, a double agent, whose mission was to make all reforms and progress toward democracy fail, which would explain the fire at the Group’s headquarters, to wipe out all traces, and also the fact that I had never been bothered.

The attack at the Café Hafa seemed to me particularly cowardly and worrisome, maybe because the victim could have been me, Judit and me, maybe because it was on my territory, here and now, and no longer a rumor — a tremendous one, true, but far away. I have to confess, for a long time I was afraid, when I’d sit down at a café in Tangier, of seeing Bassam appear, sword in hand.

I had to stop thinking about these things too much if I didn’t want to become completely paranoid.

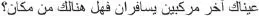

Fortunately the dead soldiers, Casanova and my poems for Judit left me little free time.  Your eyes are the last boat leaving, can you make room for me?

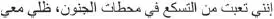

Your eyes are the last boat leaving, can you make room for me?  For I am tired of wandering through the harbors of madness. Stay with me! So that the sea will keep its color, and so on, always Nizar Qabbani. My idea was, of course, to end up composing my own verses without the help of my prestigious elders, but that was a lot of work. My Poem Number One, the first that was really mine, was the following:

For I am tired of wandering through the harbors of madness. Stay with me! So that the sea will keep its color, and so on, always Nizar Qabbani. My idea was, of course, to end up composing my own verses without the help of my prestigious elders, but that was a lot of work. My Poem Number One, the first that was really mine, was the following:

Start of the warm season

Here I am

Explorer lost beneath his ceiling fan

A telephone

A computer

A love made of wax I watch its drops fall

To seal my letters

Tonight I will read Casanova

Thinking of you

I will bathe in your eyes on every page there is a woman

Who will look like you

Every night

I hold a masked ball at the end of the world

For naughty ghosts like you

Judit would have preferred me to write her poems in Arabic, after all that’s your language, she said, it’s the one you know best, and she was right of course, but I couldn’t manage it: Arabic poetry is infinitely more beautiful and complex than French; in Arabic, I felt as if I were writing sub-Qabbani, sub-Sayyab, sub-sub-Ibn Zaydún; whereas in French, since I hadn’t read anything, any poet, or very little, aside from Maurice Carême and Jacques Prévert at school, I felt much freer. The ideal thing would have been to write in Spanish, that’s for sure: I could see myself composing a collection entitled El Libro de Judit, The Book of Judit, but that wasn’t going to happen anytime soon.

Читать дальше

Your eyes are the last boat leaving, can you make room for me?

Your eyes are the last boat leaving, can you make room for me?  For I am tired of wandering through the harbors of madness. Stay with me! So that the sea will keep its color, and so on, always Nizar Qabbani. My idea was, of course, to end up composing my own verses without the help of my prestigious elders, but that was a lot of work. My Poem Number One, the first that was really mine, was the following:

For I am tired of wandering through the harbors of madness. Stay with me! So that the sea will keep its color, and so on, always Nizar Qabbani. My idea was, of course, to end up composing my own verses without the help of my prestigious elders, but that was a lot of work. My Poem Number One, the first that was really mine, was the following: