The twenty-odd million real Volkswagen Beetles that have been produced clearly resemble each other in all the important ways; their lines, their profile, their layout. Despite changes in engine capacity or window shape or headlight design, they have far more similarities than they have differences. A Beetle standing alone is one thing, but whenever two or three stand side by side we are able to compare and contrast, to see the different interpretations and patinas wrought upon the cars. Even if the owner doesn’t actively personalise or customise the Beetle directly, it becomes unique by virtue of dents, scrapes and resprays. This is a means by which we humanise a machine.

♦

In 1992 I was telephoned by Catherine Bennett of the Guardian who was writing an article on collecting and collectors. When the article appeared she quoted me as follows:

“I think collecting’s a weird thing, a very uncreative activity,” says Geoff Nicholson, though he has a growing heap of toy Volkswagen Beetles. “I suppose in the real world I’d quite like to collect real Volkswagens, and having models of them kind of puts you in control of a very tiny world. It sounds sort of pathetic and twisted doesn’t it?”

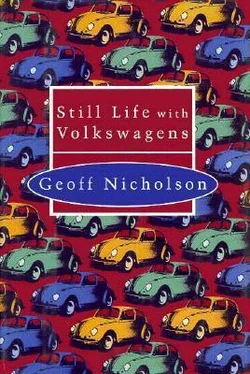

I think I’m prepared to stand by this. However, several things need to be said. First, I’m not sure I do want to own a collection of real Volkswagens. Owning real cars is a demanding, frustrating and expensive business. They go wrong, they need constant attention, and even when looked after properly they still deteriorate and decay. A collection of models or memorabilia doesn’t. It remains intact and, with a modicum of luck, becomes increasingly valuable. Secondly, being in control of a tiny world seems to me exactly what a novelist does so perhaps it isn’t so pathetic and twisted after all. And thirdly, it is an outrage to suggest that my Beetle collection is a ‘growing heap’. My Volkswagens are cherished, loved, kept on shelves, in boxes and display cabinets, so that my flat, it might well be said, looks like a still life with Volkswagens.

Nine.Bonfire of the Volkswagens

Mrs Lederer moves around her apartment, plumping a cushion here, making a minor adjustment to a flower arrangement there. She wants the room to look right. Somehow she knows — he’s about to arrive. She doesn’t know his name or what he will look like, but she wants to be absolutely ready for him. She hears tyres on the gravel and she looks out to see a Mercedes pulling into the drive. The car stops and a man gets out, a complete stranger, and yet there is no-mistaking him. It could only be Phelan. He looks strong and determined, eager but not hasty.

He rings the front doorbell and she waits a moment before going to answer it. She checks herself in the hallway mirror then opens the door wide and invites him in. He had imagined that he might have to use persuasion, coercion, even force on Mrs Lederer but her manner is entirely open and cooperative. It looks like there will be no problems here.

“Mrs Lederer,” he says. “I’m very pleased to meet you.”

She smiles and nods but says nothing.

“You have something I want,” he adds.

“Yes,” she says. “I think I do.”

“Have you been expecting me?”

“You or someone like you.”

He nods sympathetically, a family doctor making a house call. “And you know why I’m here.”

“I can guess. Long before Carlton Bax disappeared, he gave me a package. I thought it was a slightly odd present at the time but I tried to look grateful. When Marilyn disappeared too, I made one or two deductions and suspected that someone would be coming to reclaim that present sooner or later.”

“I think you’re being very sensible about this,” he says. “Now show me the Volkswagen.”

“It’s upstairs,” she says and she leads him from the living room up to her bedroom. The bed is unmade’and the room smells of bodies.

She goes over to a carved oak chest at the foot of the bed and lifts the lid. She tries hard to be casual. She reaches inside and pulls out an old but innocuous looking cardboard box, no more than a foot long. It is scuffed, discoloured and it has some indecipherable German writing on it. She hands it to Phelan. He takes it from her as though it might explode. His hands betray a slight tremor as he places the box on the dressing table and carefully opens it. Within is a small glass case with a wooden base, and set on that base is the object of all his needs and fascination; Paul Loffler’s automaton, Hitler’s Beetle.

He removes the cardboard box, takes off the glass case and stares fixedly at the naked reality of the model. He glances up at the angled dressing table mirrors and sees three reflections of the car and himself, multiple images that project through time and history.

He touches the handle delicately, just the way Adolf Hitler must have done all those years ago. He knows it is only his imagination, and yet the brass of the handle feels hot, as though there is some potent electric current coursing through it. He begins to turn the handle and gently, slowly, the sun roof of the Volkswagen rolls back. He sees the naked figures of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun, delicate, absurd, utterly obscene. He can hear the whirr of tiny gears and cams moving effortlessly inside the car. The operation is smooth and reassuring. With every turn he can feel his powers growing. Now that he has this, nothing can stop him.

He prolongs the sequence, savouring each movement of the model figures, each turn of the mechanism, until both he and the automaton of Adolf Hitler can delay no longer and the tiny shower of diamond dust sprays from Hitler’s oversized bone penis and the sun roof snaps shut.

Phelan is aware that he has an erection, but it is not because the pornography of the automaton has aroused him. It has more to do with power, with the anticipation of conquest and domination. He is also aware that his skin feels like sandpaper, that the light in the bedroom has become thickly luminous and that he may be about to sob.

He tries to collect himself. Swiftly but lovingly he returns the Volkswagen to its case and then to its box. He picks it up, holds it firmly in both of his big, beringed hands.

Suddenly Mrs Lederer slaps him across the face with all her might. It is a spiteful and shocking blow, delivered with a strength that comes from some fierce, surprising place deep inside her.

“If you’ve done anything to my daughter…” she says.

“Your daughter is just fine,” he says. “She’s with her boyfriend.”

She says nothing.

He rubs his cheek, at least partly in admiration of her power.

“You’ve done well, Mrs Lederer,” he says. “You’ve done the right thing in handing over the automaton. When this whole business is over, I could have a need of someone like you.”

She stares at him coldly, a little contemptuously, and yet there is something in her face that tells him that their needs might not be entirely at odds.

♦

On Friday afternoon they start to arrive. They come from everywhere, with their different hopes and expectations and modes of transport. The New Agers come in their buses and vans and converted ambulances, and some even on foot. The Volkswagen enthusiasts arrive in their campers and Bajas, their splits and ovals, their Karmann Ghias and Jeans and Super Beetles, some Cal look, some Resto-Cal, some customised, some completely standard. The camp followers arrive too. For the New Agers there are vegetarian food stalls, tarot readers, astrologists, vendors of crystals and aura goggles. For the Volkswagen enthusiasts there are the sellers of dress-up engine parts, customisers, engine tuners and rebuilders, dealers who specialise in Volkswagen toys and collectables.

Читать дальше