“What you don’t understand is that we’re being kept down out there. All the way down. In my town you couldn’t vote unless you passed a literacy test. How does that stop colored folks from voting, you ask? You didn’t see what the colored school was like, how big the classes were. The teachers did what they could, but half my male cousins could hardly read. They lost patience before the girls did. No matter how literate a colored man was, there was always some excuse to whip him. There were other things too. Little things. You’d save up and go out for a nice night at a nice place, all right, fine. All the high-class places we were allowed to go to, they were imitations of the places we were kept out of — not mawkish copies, most of it was done with perfect taste, but sitting at the bar or at the candlelit table you’d try to imagine what dinnertime remarks the real people were making… yes, the real people at the restaurant two blocks away, the white folks we were shadows of, and you’d try to talk about whatever you imagined they were talking about, and your food turned to sawdust in your mouth. What was it like in those other establishments? What was it that was so sacred about them, what was it that our being there would destroy? I had to know. I broke the law because I had to know. Oh, only in the most minor way. Gas station restrooms when Gerald would drive me cross-state on vacation — one day I used the White Only restroom and nobody noticed me. Gerald begged me not to, but I just got my compact out, repowdered my face, and walked in. I felt like laughing in all their faces. The rest room experience is more or less the same, in case you were wondering.”

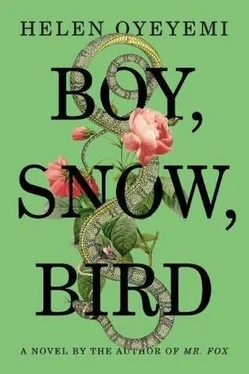

“Olivia,” I said. “Look at Bird. Look at her.” I drew the baby blanket down a little so that Olivia could really see her. But the woman just wouldn’t look, and it broke my heart.

“Every now and then there’d be a colored cleaning lady in there, in the White Only restroom, I mean, scrubbing a washbasin that nobody was using right then. And she’d look at me and know, and I’d look at her. They didn’t do anything or say anything, those cleaning ladies, but for hours and hours afterward I’d just want to pull all my skin right off my body. So I said to Gerald: We’ve got to go north, let people take us how they take us, then we won’t feel like we’re betraying anybody. But it’s the same thing over here. Same thing, only no signs. The places you go to, do you see colored people there? Let me answer that for you. You see them rarely, if at all. You’re trying to remember, but the truth is they don’t exist for you. You go to the opera house and the only colored person you see is the stagehand, scattering sawdust or rice powder or whatever it is that stops the dancers slipping… folks would look at him pretty hard if he was sitting in the audience, they’d wonder what he was up to, what he was trying to be, but being there to keep the dancers from slipping is a better reason for him to be there, he’s working, so nobody notices him but me. Listen, I love that Grand Theater down in Worcester and I love all that dancing I see there, been there at least once a year for the past… oh, how old is that son of mine… for the past thirty-seven years or so. Almost forty years! But sometimes right in the middle of the second act my vision darkens just like a lantern shade’s been thrown over it, and the dancers are colored, every shade, from bronze to tar, and every hand touching strings in the orchestra is colored too, and the tops of their heads are woollier than sheep, and the roses in my lap, the ones I throw to the prima ballerina at the end, even the petals of those roses are black, burnt black. And then I think, Well, it’s out, the truth is out…”

She glanced at Bird. “This one’s dark like my eldest, Clara. See if Clara will take her.”

—

i said i didn’t care that Bird was colored. I said that to Mia, and to Webster, and to Mrs. Fletcher, who replied: “That’s the spirit. Keep saying it until it’s true.”

Nothing got past Mrs. Fletcher. It’s true that it was hard. Olivia and Gerald attended Bird’s christening, and Gerald kissed her, but Olivia didn’t. And it was hard to take Bird for walks, pushing her stroller around town, and watch people’s faces when they saw her. I saw them deciding that if Arturo meant to claim her as his daughter then they weren’t going to contradict him. Once I passed Sidonie and Merveille, deep in conversation, the daughter pushing her mother’s wheelchair, and I almost escaped them, but Merveille instructed Sidonie to bring her up to the stroller so she could bless the baby. Merveille invited me to coffee when she found out I’d lied about being Sidonie’s teacher, and it was excruciatingly awkward for the first half hour or so. I felt sick about having lied to her; there are people it’s a bad idea to tell the truth to, but never Merveille. She didn’t have to set me at ease — not by any means — but she did, by telling me about her grudging respect for Olivia Whitman. She said Olivia’s “masquerade” had been ugly, but that she couldn’t help but appreciate a woman with sangfroid. “Let us say that means ‘cold blood.’ No — nerve is what she has. Nerve.” It turns out Olivia respects Merveille Fairfax too, because of the stink she raised over a decade ago about Flax Hill’s colored children having to go to a separate school when it was their right by law to be educated alongside their white peers. Apparently Merva got up a letter-writing campaign, The Boston Globe ran an editorial piece about the situation, and the school board gave in under the pressure. Olivia said most people weren’t overtly against joining the schools, more people than she expected were in favor of it, but a few called Merva bad names in the street and asked her if she thought her daughter was too smart for the colored school. And Merva smiled and said: “Every single child in this town is too smart for the colored school.” That put her on Olivia’s list of people not to trifle with.

I looked at the sky while Sidonie and Merveille gasped and cooed over Bird, so I didn’t see their expressions. But when they finally let me go on my way, Sidonie put her hand on my shoulder, and that hurt me all the way home.

Yes, it was hard. Snow would place a finger on each of Bird’s palms and raise her little hands up when they closed into fists. She’d say: “I’m your best friend, Bird.” Bird seemed to understand and believe this, and her eyes searched for her sister when she was away. Bird adored Snow; everybody adored Snow and her daintiness. Snow’s beauty is all the more precious to Olivia and Agnes because it’s a trick. When whites look at her, they don’t get whatever fleeting, ugly impressions so many of us get when we see a colored girl — we don’t see a colored girl standing there. The joke’s on us. Olivia just laps up the reactions Snow gets: From this I can only make inferences about Olivia’s childhood and begin to measure the difference between being seen as colored and being seen as Snow. What can I do for my daughter? One day soon a wall will come up between us, and I won’t be able to follow her behind it.

Every word Snow said, every little gesture of hers made me want to shake her. Arturo told her I was just tired. It was true that I was up at whatever hour Bird chose. I rarely let him go to her instead. He got good at changing her diaper really fast, before I really noticed what he was doing. “You think I’m gonna let you tell her I never helped out?” he said. Our daughter suckled so slowly, with the sucked-in cheeks of a wine-tasting expert. I’d nod over her while she fed, slipping in and out of sleep.

“Snow is not as wonderful as everybody thinks she is,” I said to Mia on the telephone, and my reflection smiled bitterly at me.

Читать дальше