The robber and I went back to the hotel room. I sat in the bathroom and folded the toilet paper into a point like I worked there. When I went into the bedroom, he said he wanted to make love on sheets. I said No. He said Are you still mine? I still love you, do you love me? and I said I don’t even know your first name, and for that matter, I don’t know your last name either and besides, you just let our love plop into the ocean and so how am I supposed to love you now? I put my hands on my hips.

He said It wasn’t our love that plopped into the ocean, Penny, it was just the ring, and I said But this was the ring from the flour jar and I don’t know how to be yours without it.

He held my face in his hands. I looked out past the window to the foam crashing. It was pink.

Listen, I told him. I’m confused. I’m going home.

I took a shuttle to the Tahiti airport by myself. I left the robber sitting on the made bed, staring at the wall. I sat in the back of the shuttle bus and didn’t talk except in curt one-word answers and the shuttle driver kept asking me questions that required more than one-word answers and he kept calling me Sugar and I was getting more and more annoyed and wanted to yank the steering wheel out of his hands and throw it out the window until out of the blue he gave me an idea. I barely remember paying him because I thought about this idea from the moment it came to me, and I thought about it the whole plane ride, through the snack and through the movie and through the dinner, and that’s where I went first. I didn’t even stop home to drop off my bags.

The white cat was still there and purred the second I touched it but more important, the sugar jar was still there too. I took it in my lap, opened the lid and peeked inside. The grains glittered.

Oh sugar, I said into it. You are the strongest of all.

I picked up their phone — it was a tortoiseshell phone with gold buttons — and called direct to the hotel room in Tahiti. To my surprise, the clerk said we had checked out several hours ago and just then there was a rattle at the window and in stepped the robber.

How did you know? I beamed, phone receiver in hand, and he shrugged, face tired and sunburned.

It was a good guess, he said. Madame Butterfly signs out and all.

We leaned forward and had an awkward hug. I held on to his elbow. He nudged his chin into my neck.

Pulling away, I held up the jar. So look at this, I said. Maybe this will help things.

What is it? he asked.

It’s that special sugar.

Oh, he said. Well. I’ve always liked sugar.

I felt a little nervous but he gave me a good supportive look, so I dipped a finger into the sugar and licked it off. Mmm, I said, mmm, you’ve gotta try this. The grains sparkled on my tongue. The robber sat down in one of the wicker kitchen chairs next to me.

It’s really good, I said.

He dipped in his own leathered finger and took a tentative lick off the glove. I watched his expression carefully. The house seemed very quiet except for the precise ticking of the clock above the kitchen table.

Do you feel any different? I asked.

Not yet, he said.

He put his finger in it again and I did too and once we touched fingertips and he curled his knuckle around mine and squeezed.

Hello there, I said softly, to our fingers.

He put his hand on my leg. My leg leaned into his hand.

I think we should eat it all, I stated. He moved closer to me. I’m full, he said. Keep eating, I said.

But Penny, it tastes just like regular sugar, he whispered into my ear.

Sshh, I murmured back, touching my shoulder to his, scooping up a new pile of grains into my hand. Don’t tell.

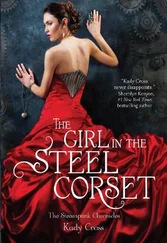

THE GIRL IN THE FLAMMABLE SKIRT

When I came home from school for lunch my father was wearing a backpack made of stone.

Take that off, I told him, that’s far too heavy for you.

So he gave it to me.

It was solid rock. And dense, pushed out to its limit, gray and cold to the touch. Even the little zipper handle was made of stone and weighed a ton. I hunched over from the bulk and couldn’t sit down because it didn’t work with chairs very well so I stood, bent, in a corner, while my father whistled, wheeling about the house, relaxed and light and lovely now.

What’s in this? I said, but he didn’t hear me, he was changing channels.

I went into the TV room.

What’s in this? I asked. This is so heavy. Why is it stone? Where did you get it?

He looked up at me. It’s this thing I own, he said.

Can’t we just put it down somewhere, I asked, can’t we just sit it in the corner?

No, he said, this backpack must be worn. That’s the law.

I squatted on the floor to even out the weight. What law? I asked. I never heard of this law before.

Trust me, he said, I know what I’m talking about. He did a few shoulder rolls and turned to look at me. Aren’t you supposed to be in school? he asked.

I slogged back to school with it on and smushed myself and the backpack into a desk and the teacher sat down beside me while the other kids were doing their math.

It’s so heavy, I said, everything feels very heavy right now.

She brought me a Kleenex.

I’m not crying, I told her.

I know, she said, touching my wrist. I just wanted to show you something light.

Here’s something I picked up:

Two rats are hanging out in a labyrinth.

One rat is holding his belly. Man, he says, I am in so much pain. I ate all those sweet little sugar piles they gave us and now I have a bump on my stomach the size of my head. He turns on his side and shows the other rat the bulge.

The other rat nods sympathetically. Ow, she says.

The first rat cocks his head and squints a little. Hey, he says, did you eat that sweet stuff too?

The second rat nods.

The first rat twitches his nose. I don’t get it, he says, look at you. You look robust and aglow, you don’t look sick at all, you look bump-free and gorgeous, you look swinging and sleek. You look plain great! And you say you ate it too?

The second rat nods again.

Then how did you stay so fine? asks the first rat, touching his distended belly with a tiny claw.

I didn’t, says the second rat. I’m the dog.

My hands were sweating. I wiped them flat on my thighs.

Then, ahem, I cleared my throat in front of my father. He looked up from his salad. I love you more than salt, I said.

He seemed touched, but he was a heart attack man and had given up salt two years before. It didn’t mean that much to him, this ranking of mine. In fact, “Bland is a state of mind” was a favorite motto of his these days. Maybe you should give it up too, he said. No more french fries.

But I didn’t have the heart attack, I said. Remember? That was you.

In addition to his weak heart my father also has weak legs so he uses a wheelchair to get around. He asked me to sit in a chair with him once, to try it out for a day.

But my chair doesn’t have wheels, I told him. My chair just sits here.

That’s true, he said, doing wheelies around the living room, that makes me feel really swift.

I sat in the chair for an entire afternoon. I started to get jittery. I started to do that thing I do with my hands, that knocking-on-wood thing. I was knocking against the chair leg for at least an hour, protecting the world that way, superhero me, saving the world from all my horrible and dangerous thoughts when my dad glared at me.

Stop that knocking! he said. That is really annoying.

I have to go to the bathroom, I said, glued to my seat.

Go right ahead, he said, what’s keeping you. He rolled forward and turned on the TV.

I stood up. My knees felt shaky. The bathroom smelled very clean and the tile sparkled and I considered making it into my new bedroom. There is nothing soft in the bathroom. Everything in the bathroom is hard. It’s shiny and new; it’s scrubbed down and whited out; it’s a palace of bleach and all you need is one fierce sponge and you can rub all the dirt away.

Читать дальше