So I cannot go back to Uganda till Christmas. It will take four months to earn the money I need.)

It is possible there has been a slight misunderstanding. I thought of this after she really started screaming. Surely even Miss Henman would not believe that I was doing bad things with her son? I Mary Tendo! A Ugandan Christian!

And then I started to laugh a little. And then I started to laugh a lot.

Of course, nothing bad is happening. Nothing, at least, that could make me pregnant. Of course it is different with my friend the accountant because he has promised to marry me. God is my witness, I’m an honest woman.

Many things Miss Henman does not understand, but this is the one that made me so angry that I had to pretend I was going home.

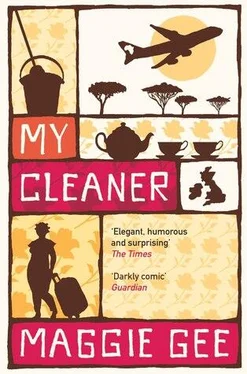

Because I was her cleaner, she thinks I always will be. When she looks at me, she sees ‘my cleaner’. When we had the argument, she called me ‘my cleaner’. She thinks that Mary Tendo is a name for a cleaner, like Vanessa Henman is a name for a professor .

(And when I was here before, eleven years ago, the Henman made me laugh when she talked about me. She thought I was too stupid to understand. But I noticed that, after I started looking after Justin and tidying up a little in the afternoons, she changed what she called me from day to day, when different people came to the house. Sometimes she said, ‘This is my cleaner’ and sometimes she said, ‘This is our nanny’. So she got two servants. But she only paid one.)

In fact, Mary Tendo is educated, as educated as Dr Henman. I am BA Hons, Makerere.

And when she screamed at me, I answered her politely. “I was your cleaner. I’m not your cleaner now. I was your cleaner, Miss Henman, Vanessa.”

The Henman thinks that cleaning is something easy. But Henman never really cleans her house. Every now and then when she cannot do her writing she chooses something small, like a light or a bath tap, and polishes it like a crazy woman. She rubs it like a wasp that is trying to sting. She shines it as if it will light her path to heaven. Then she comes to me and shows me her work. “You see how nice it looks when one makes an effort.”

I do not say, “But it took you two hours. When I was your cleaner I had only three hours to clean the whole house, which is big, and old, with five dusty bedrooms and three sitting rooms.” I repeat what she says, and look at the floor. I say, “Very nice, when one makes an effort,” but it comes out wrong, and I almost laugh, and she notices, and looks at me strangely.

In fact, I am starting to rebel against her, because I am tired of pretending to be humble. I remember a story about Idi Amin, who was our leader when I was a child. He was a terrible man, but also very funny. When the British economy was in trouble, he started a ‘Save Britain Charity Fund’ in Uganda, and telegrammed the UK prime minister to tell him he was sending 10,000 Ugandan shillings ‘from his own pocket’, and a lorry-load of vegetables from the people of Kigezi.

The British government ignored his offer. Probably the British think Ugandans are simple, and do not recognise our sense of humour. And yet Amin renamed himself ‘The Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in general and Uganda in particular’!

Justin lies awake in the moonlit dark, looking at the back of Mary’s head, its crisp curls just visible, springy and resilient, tough enough to survive, and save him. Mary could not sleep with the curtains closed, and so now he sleeps with the curtains open. Everything is different now Mary is here.

Perhaps he does not need to wake her up. Perhaps the panic will not come tonight, the feeling of falling and falling for ever, the demon voices that come and accuse him of all that he has left undone. Sometimes it’s enough just to see her there. To know that someone is there just for him. Someone who will let him reach out and touch her. Who came round half the world to find him.

His mother had tried to send her away. Although she denies it, he knows it is true. Two days ago he woke to the sound of voices, and his mother was screaming at Mary in the hall. Mary stood there with her coat on, a poor cotton thing with big shoulder-pads and shiny buttons, and her cases beside her, ready to go. She was calm, but she was talking loudly. Neither of them was listening. Mary was wagging her finger at his mother. Justin stood on the stairs, his heart in his mouth. Both of them were ignoring him. In this house, Justin is still a child. But he made himself go down and join them.

“Are you driving her away?” he remembers shouting. And other things he should perhaps not have said. “I hate you, Mother. You’re driving her away.”

“You don’t understand.” She had turned on him. Her mouth was thin and furious, her pupils were tiny, her nose big and bony, like a witch. He had been shocked by how old she looked, which made him wonder, for a second, whether his mother was going to die, and then he could go and live with his father, if his father would let him live with him.

Will he always have to live with his parents?

But he loves his mother, painfully, deeply. He is like a sucker, still joined at the root. How would he live without his mother? How would he live without Mary?

All his life he has felt abandoned. He has been left at so many places: Baby Reading, Junior Einstein, gym for toddlers, swimming for tiddlers.

How could he stop what was happening? “You’ve driven her away, you’ve driven her away,” he had sobbed, stupidly insistent. “Mary is the only person who can help me.” But it only made his mother scream louder.

And then his father rang on the door. They had all stopped dead, in total silence.

Before he rang again, Justin managed to say, “If Mary goes, I will never forgive you.” His mother stared at him, eyes wild.

Then his father came in and it all calmed down, though Mary refused to go from the hall or move her cases till his mother said ‘Sorry’. She did say ‘Sorry’, which astonished Justin. His mother has never said ‘Sorry’ to him.

And his father made them all a cup of tea, and then his parents had begun to quarrel, as they usually did, and life went back to normal.

In the end it turned out it was his father’s fault, according to his mother, for not being there.

How could his father cause the quarrel by not being there?

It is true that his father’s been away more than usual. He has a new girlfriend, whom they’ve never met. His mother had told him she was practically a schoolgirl, but later he found out that this wasn’t true. Soraya is twenty-nine, and an art teacher. His mother calls Dad ‘the cradle-snatcher’, which makes Justin feel ashamed for his father.

Of course his father is really old, so Soraya must be blind, or desperate. All the same, Justin would like to meet her. Perhaps she is easier to live with than his mother.

Sometimes he thinks that his mother is a demon. Sometimes she makes him feel hopeless, useless. His heart starts beating too fast again. Can he ever be good enough to please his mother?

Mary stirs in her sleep and snores gently. The sound is soothing, like a pigeon cooing. Justin stretches out his hand and feels the heat of her shoulder, very gently, not quite touching her, just sensing the living, easy warmth, and his body relaxes, and he breathes deeply.

He thinks about some of the things Mary says. He knows his mother believes she is stupid, although she has never actually said so: but when he was a child, and Mary looked after him, he used to pass her sayings on to his mother, and she would get a strange, superior expression, and say, “Remember she is African. They have a different way of doing things. Remember that you are an English boy.” And he would feel embarrassed, and wish he had not told her.

Читать дальше