We must leave here at once, my partner cried, waving her arms and jumping up and down in front of the farmer.

He shook his head. He was staying put, he said; the rest of us should go. That was out of the question, Heinrich replied. We — he meant my partner and me — wished to leave; he and Eva were staying. We two should drive to the nearest town and wait at a hotel there. This business would soon be over, he said, and we could keep abreast of developments by telephone. I asked my trembling partner if she approved of this course of action.

Just at that moment, Eva appeared at the living room window. We must see this, she called.

Hurrying over to her, we looked through the window and saw an aerial shot of the property on television. Everyone was clearly visible: the farmer with his gun, us outside the window, the parked cars — even the dressed-up cat fleeing from the noise in terror.

Heinrich left the window. Fantastic, he said, we’re on television! He hurried inside and turned on the video recorder so as to tape the broadcast. Then he rejoined us outside the house.

Look, he exclaimed, policemen!

We looked in the direction of his outstretched arm. Sure enough, a contingent of policemen with dogs was coming into view some four hundred yards away.

He’s here, I tell you, my partner yelled, and she ran off toward the oncoming policemen.

Eva made to go after her, but Heinrich told her to stay where she was. My partner’s nerves were completely shot, he said; if she would feel safer with the policemen, we oughtn’t stop her. He added that it was annoying we couldn’t hear what was being said on television because of the racket the helicopters were making.

We stood idly beside the window for a while. On the screen inside we saw my partner running toward the line of policemen, who were steadily converging.

Eva said she would bring out some drinks for us. No one else considered going back inside the house — that much was clear. Shortly after she disappeared into the building, she opened a kitchen window. We should go around the house and look in the other direction, she called. We complied with her request and were unsurprised to see dozens of policemen around two hundred yards away. They were also making straight for the properties of the Stubenrauchs and their neighbors.

We returned to the front of the house and the television window, whichever. The contingent of policemen with my partner in their midst had approached to within approximately a hundred yards. A police car could be seen on television, driving along the road with its blue lights on.

Eva came out into the yard with a tray of drinks. She had heard on the radio that the inhabitants of the district were being instructed to go into their homes and lock their doors because of the hunt for the killer. With a nervous smile, she wondered if that applied in our case. After all, she said, the forces of law and order responsible for our protection were very close at hand and present in large numbers.

Heinrich laughed. No, he replied, he thought it was permissible for us to remain outside the house. He gave the nearest helicopter a wave. I saw this on the television and turned around.

We could already make out the faces of the approaching policemen. Although with them, my partner didn’t speak to anyone and remained on the sidelines. She was only wearing a T-shirt, so someone had draped a jacket around her shoulders. She was staring at the ground. The policewoman walking along close beside her was eying her with concern.

When the squad was within approximately twenty-five yards of us, it came to a halt. With a laugh, Heinrich called to my partner that all danger had been averted. He got no response, however. The body of policemen approaching from the other direction could now be seen from where we were standing. They halted about a hundred feet away.

We saw on television that the property was surrounded on all sides. The police car, lights flashing, came into view once more. The farmer asked both police contingents what was up. Were Herr Schober or Herr Haberfellner with them? One of the policemen called back, telling him to lay down his weapon at once. After some prevarication, the recipient of the order obeyed. The television deemed this incident worthy of a close-up.

The police car drove into the farmyard, siren wailing, and pulled up. The sound of the siren ceased; the blue lights continued to flash. Three policemen jumped out of the vehicle. The senior officer put his hands on his hips and surveyed his men and us in turn. I saw on the screen how Heinrich too kept turning to look at the television, on which the three policemen’s intervention could be observed. The senior officer took a few steps across the yard. He appeared to be examining the license plate numbers of the cars parked there. Then he jerked his thumb at one of the vehicles and asked whom it belonged to.

Them, Heinrich told him — his guests, in other words, my partner and me. The television clearly showed him pointing us out.

The senior officer and one of his men came over to me. We’ve got him, he said; that’s the man.

On the screen, I saw Eva, who was standing beside me with the tray, retreat several feet. Behind me, my partner started to scream. On the television, I saw handcuffs being produced and turned around. The officer in command announced that I was under arrest; I was charged with having murdered two children.

I do not deny this.

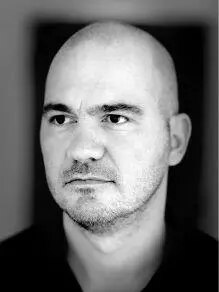

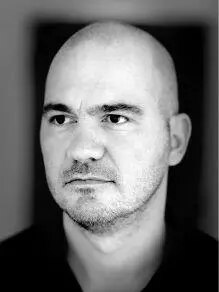

Photo by Ingo Pertramer © 2010

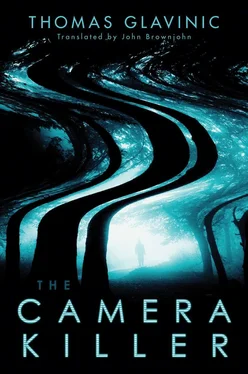

THOMAS GLAVINIC IS CONSIDERED one of the guiding voices in Austrian literature. Born in 1972, he is the author of several novels, as well as a number of essays and short stories. His work has garnered both critical acclaim and commercial success and has been translated into sixteen languages. Glavinic worked as an advertising copywriter and taxi driver before releasing his debut novel, Carl Haffner’s Love of the Draw , in 1998. The Camera Killer is his third book to be published in English. It was awarded the 2002 Friedrich-Glauser Prize for crime fiction and has been adapted for the screen. Glavinic was short-listed for the German Book Prize in 2007, and his How to Live , forthcoming from AmazonCrossing, reached #1 on the Austrian best-seller list.

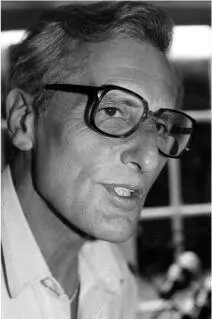

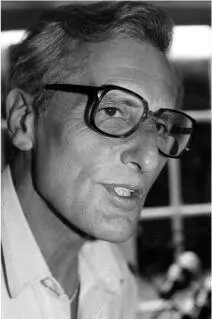

Photo by Sherborne Photographic

ORIGINALLY A CLASSICIST WHOSE school diet from age eight included ancient Greek as well as Latin, John Brownjohn won a major scholarship to Oxford, from where he graduated with honors. Thereafter, partly because he hails from a ramified family whose members fought on both sides during World War II, he made the transition to modern languages and a career as a literary translator that has earned him critical acclaim and many British and American awards. In addition to translating the better part of two hundred books, he has produced English versions of many German and French screenplays and cowritten several feature films with Roman Polanski.