They looked at each other and drew the sweetness against the other’s lip. Then they left the top and went to the mouth of Thoon.

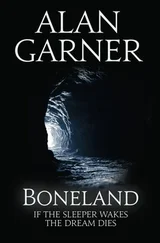

Nan Sarah felt the arch of the cave, the stones of the back, the crevice, the bottom slab.

“Whoever can have made this?”

“Summat bigger nor us, wife. There’s things up here. I can tell you. What! A man can see all sorts.”

They sat inside Thoon. The rock took them and held them. The first of night moved down the sky and the land merged.

“I never thought as how there were so many hills,” said Nan Sarah. “Jack, it fears me for you now.”

“You need never fear for me, Nan Sarah. Here’s where I was born, you daft woman. There’s no hurt.”

“Born here? Where?”

“On this very stone. At least, that’s what’s said. But I reckon it was some wench as couldn’t thole, and the chap fetched it and left it. But it couldn’t have been long. Me father told me. There was a great dumberdash, and it let against Shining Tor, above Longclough. Mark’s there still, if you look. Anyroad, me father, he’s leading his kyne up Thursbitch; and he sees this here thunderbolt hit the side of Tor; and didn’t they run! So he’s going to look, when he sees me lying in Thoon, snug as a bug in a rug. Leastways, that’s what he says. But I’ve always reckoned as it was a bit too much chance, like. Have you not been up before?”

“All them hills. Why should I?” she said. “There’s work for neither man nor beast in these parts.”

“There’s work for me,” he said. “And for me beasts. There’s not a brow nor a clough nor a slade nor a slack, nor a cop nor a crag, nor a frith nor a rake, nor a moss nor a moor, as we don’t know it, by day and by night, for as far as you can see and further.”

“Is there no end?” she said.

“Nobbut The Unvintaged Red Erythræan Sea. Same as they say.”

“That big pond down there?”

“That’s no pond, Nan Sarah. It looks like it now, I’ll grant you. But you get down there and it’s neither flat nor wet; and right t’other side’s Chester. And that’s a two-day jag and a whealy mile, I can tell you. And I’ll be laying me head there night after next.”

“You shall come back?”

“I shall come back. I’m the promise as always comes back.”

“I never knew,” she said.

“Well, you know now. A man wi’ salt in his pocket always gets home.”

“There’s a star falling. See at it!”

“Following its road. Same as me.”

“SAL. PLEASE. USE the gate.”

“I prefer the griddle cat.”

She teetered over the steel bars.

“You’ll fall.”

“Shut up, Ian. I’m concentrating.”

“Then hold on to something.”

“I like the odds.”

He closed the gate.

“Put your leg in bed.” She linked arms with him, and they went down and up to Howlersknowl.

Beyond the farmhouse the track turned off and climbed aslant the field. To the side and below was a yellow boulder with a steel ring fixed into the top. The soil was bare around it and its sides were polished dark with the rubbing of sheep.

They passed on, up to the gateway of the valley mouth.

“You were right about the stones,” he said. “This one doesn’t look like a post, either. It’s much too big. What else can it be?”

“I’ve no idea. Oh. The valley.”

“Nothing’s changed,” he said. “Just as it was.”

“Wrong. Everything’s different.”

“What do you mean, everything?”

“Over the winter it’s moved about three point seven millimetres.”

“You are absurd,” he said.

“On the contrary. I’m approximately accurate.”

She put her head on his shoulder.

“That’s an interesting feature.”

“What is?” he said.

“The outcrop on the ridge, to the left, with a track going up.”

“Sal?”

“Yes?”

“Look. Look at it. Look at it closely.”

“Why?”

“What do you know about it?”

“At this distance? It’s an outcrop. Rough Rock or Chatsworth Grit, probably. At a pinch it could be Roaches or Carbor. Namurian, certainly. What’s the matter?”

“Nothing.”

“Yes there is.”

“No. Really.”

“Come on. Tell Mummy.”

“It’s nothing.”

She held his arms, looked hard at him.

“I’ve done it again, haven’t I?”

He did not answer.

“Yes. I have. I have. But what?”

“Let’s go back.”

“Ian.”

“Come on.”

“No. I mustn’t hide. Mustn’t dodge. I can’t pretend. I must fight this thing. Tell me.”

“We parked, and walked from Pym Chair,” he said. “Remember?”

“Pym Chair?”

“Where they were flying their model planes.”

“We did?”

“We walked along the ridge.”

“And I don’t like crowds.”

He nodded.

“All those people.”

“Yes.”

“A rock.”

“Yes.”

“There was a rock.”

“Yes.”

“Hollow. We sat. It was good.”

“Yes.”

“And that’s it.”

“Yes.”

“Oh, Jesus Christ.”

“We can go somewhere else.”

“No. Here. There’s something here. For me.”

She huddled on a remnant of wall, her back against the big stone, and looked inwardly along the valley. He sat next to her, holding each hand in his.

The air was only far sounds.

She slammed her head on the stone and howled, thrashing from side to side; then slumped forward, her face in their hands. He felt the heat of her tears and the water from her mouth run on his palms. He held, gentle, and did not speak as she retched. Then she was quiet, and he was still.

She lifted her head and looked again. Her face was put together. Her breathing grew calm. Soon she gave him a quick little smile.

“What’s that house?”

“It’s a farm. A ruin. Thursbitch.”

“Thursbitch. Have we been there?”

“Yes.”

“Thursbitch. Yes. All right.”

The path dipped and rose as they crossed gullies running off Cats Tor and the ridge. Nearer the ruin the path cut deep through banks of purple shale.

“Is this coal?” he said.

“Almost. Aha. Just what you’d expect.”

She picked something out of the shale and gave it to him.

“It’s an ammonite,” he said.

“No. Reticulosus bilingue .”

“Which two?”

“Which two what?”

“Languages?”

She laughed. He watched her.

“Oaf. It’s one of the main horizon indicators. Different species are used to identify individual series. So hereabouts we’re in R-Two Marsdenian country. It’s only bloody jargon.”

“Wait.” He opened his bag and took out a notebook. “Marsdenian R-Two. That’s what you said on the outcrop.”

“Which goes to show how clever I am.”

They were at the ruin.

“If you’re lucky, I may find you some R. superbilingue in the brook. And don’t you dare ask if it’s polyglot!”

She walked around the ford, turning stones over and picking up shale in the bed.

“Here we are. Another present.” She put the fossil into his hand.

“I can’t see any difference,” he said.

“And that, my lad, is why I’m me and you’re you. Give or take. More or less.”

He helped her up the bank. They sat on a fallen post, and he opened a Thermos flask and poured for them both.

“Cold?”

“No. Fine. Good coffee.”

She looked around at the valley.

“Penny for them.”

“Mm.” She turned her head.

“More coffee?”

“Thanks. Oh, buggeration.”

The cup slipped and rolled down the grass. He went to pick it up, filled it again, and she took it in both hands.

Читать дальше